In this episode of the Matrix Podcast, Julia Sizek, PhD Candidate in Anthropology at UC Berkeley, interviews Biz Herman, a PhD candidate in the UC Berkeley Department of Political Science, a Visiting Scholar at The New School for Social Research’s Trauma and Global Mental Health Lab, and a Predoctoral Research Fellow with the Human Trafficking Vulnerability Lab. Herman’s dissertation, Individual Trauma, Collective Security: The Consequences of Conflict and Forced Migration on Social Stability, investigates the psychological effects of living through conflict and forced displacement, and how these individual traumas shape social life.

Herman’s research has been supported by the Fulbright U.S. Student Program, the University of California Institute on Global Conflict & Cooperation (IGCC) Dissertation Fellowship, the Simpson Memorial Research Fellowship in International & Comparative Studies, the Malini Chowdhury Fellowship on Bangladesh Studies, and the Georg Eckert Institute Research Fellowship. Along with collaborators Justine M. Davis & Cecilia H. Mo, she received the IGCC Academic Conference Grant to convene the inaugural Human Security, Violence, and Trauma Conference in May 2021. This multidisciplinary meeting brought together over 170 policymakers, practitioners, and researchers from political science, behavioral economics, psychology, and public health for a two-day seminar on the implications of conflict and forced migration. She has served as an Innovation Fellow at Beyond Conflict’s Innovation Lab, which applies research findings from cognitive and behavioral science to the study of social conflict and belief formation.

In addition to her academic work, Biz is an Emmy-nominated photojournalist and a regular contributor to The New York Times. In 2019, she pitched and co-photographed The Women of the 116th Congress, which included portraits of 130 out of 131 women members of Congress, shot in the style of historical portrait paintings. The story ran as a special section featuring 27 different covers, and was subsequently published as a book, with a foreword by Roxane Gay.

The Matrix Podcast interview focuses primarily on Herman’s research on mental health and social stability at the Za’atri Refugee Camp in Jordan, as well as her broader research on the psychological implications of living through trauma and the impacts of individual trauma on community coherence.

The research in the Za’atri Refugee Camp, Herman explains, was part of a project developed by Mike Niconchuk, Program Director for Trauma & Violent Conflict at Beyond Conflict, who created a psycho-educational intervention called the Field Guide for Barefoot Psychology. “The goal of The Field Guide is to provide peer-to-peer mental health and psychosocial support and education,” Herman explains. “It’s a low-cost intervention, and it can be scaled. The idea was that in Za’atari Camp, where mental health care is very stigmatized, there are a lot of barriers to entry. And there are a lot of needs — physical security needs and community needs — and mental health is often de-prioritized. [The Field Guide provides] one way to address the lingering psychological implications of living through conflict and forced migration in a way that is accessible, and that can be provided without attracting attention or producing any kind of stigma, and that’s really connected to the context.”

The Field Guide uses narrative storytelling and scientific education, paired with self-care exercises, Herman explains. “Each chapter starts with a narrative of a brother and sister and their lives in Syria before conflict, during conflict, during migration, and in resettlement,” she says. “Through the story, different themes and ideas and issues come up, with different physiological and psychological responses. As these different responses come up, the next part of the chapter talks about the science behind that in a way that allows for some psychoeducation on what’s happening, but allows people to engage with it through someone else’s story.”

Listen to the interview below, or on Apple Podcasts or Google Podcasts.

Podcast Transcript

[MUSIC PLAYING]

Woman’s Voice: The Matrix Podcast is a production of Social Science Matrix, an interdisciplinary research center at the University of California, Berkeley.

Julia Sizek: Hello, everyone. And welcome to the Social Science Matrix Podcast. I’m Julia Sizek, your host. Today, we’ll be talking to Biz Herman, a PhD candidate in political science and a visiting scholar at the New School for Social Research’s Trauma in Global Mental Health lab and a predoctoral research fellow with the Human Trafficking Vulnerability lab.

Her research focuses on the psychological consequences of living through conflict in forced displacement and how that shapes the social lives of refugees and support for peace and reconciliation efforts.

Today, we’ll be discussing her research among Syrians living in the Za’atri refugee camp in Jordan. So thank you so much for coming on our podcast.

Biz Herman: Thanks for having me.

Julia Sizek: So let’s just get started by hearing a little bit more about your research on trauma related distress. How did you get started on this research project at the Za’atri refugee camp?

Biz Herman: So thanks so much for having me. And this project is a collaborative project that has been in the works for many years now. I got involved in 2017. It’s a team effort with Young Conflict, which is an organization based in Boston, and Cosgrove, which is based in Jordan and has offices in Za’atri camp.

And then the research team is made up of researchers from the New School for Social Research and myself at Berkeley. And what we’ve been doing, the project was first developed by Mike Niconchuck, who is the lead author and developer of a new psychoeducational intervention called The Field Guide for Barefoot Psychologists.

And the goal with field guide is to provide peer to peer mental health and psychosocial support and education. So it’s a low cost intervention. It can be scaled. And the idea was that in Za’atri camp, where mental health care and mental health and well being is very stigmatized and there are a lot of barriers to entry and there’s a lot of needs in the camp, different kinds of physical security needs, community needs, and mental health is often deprioritized, what was one way to address the lingering psychological implications of living through conflict and forced migration in a way that was accessible, that could be provided without attracting attention or producing any kind of stigma around it and really connected to the context.

So the field guide itself has a structure where it’s very narrative based. And it uses narrative storytelling and then scientific education paired with self-care exercises to deliver the intervention. So each chapter– it’s presented as a book, and each chapter starts with a narrative of a brother and sister and their lives in Syria before conflict, during conflict, during migration, and in resettlement.

And through the story, different themes and ideas and issues come up and different physiological responses and psychological responses. And as these different responses come up, the next part of the chapter then talks about the science behind that in a way that allows for some psychoeducation on what’s happening but allows people to engage with it through someone else’s story.

And there might be some things that relate to what they might have experienced themselves, but they don’t have to– in the context of therapy, you’d have to share with whatever practitioner what had happened to you. This is a way to engage with this in a step removed but still get information that might be relevant to you and to people you know.

And then the last part of each chapter is some kind of self-care exercise to address whatever issues that might come up related to what had been discussed in that chapter. So maybe it’s a breathing exercise to help regulate your heart rate.

Maybe it’s a sort of grounding exercise to help you refocus on the present. So it’s a very applied intervention. And the goal is to use science and storytelling to help people of address underlying issues that might have been not– there might not have been space or time or funding to address in the past.

And the facilitators, it’s delivered through two modalities. It’s delivered through workshops, in-person workshops twice a week. This was pre-COVID. And then the other modality is a take home modality where people pick up a book and they have weekly check ins, where if they are experiencing distress or they had sort of adverse reactions to engaging with the material, they can get care.

But they’re sort of guiding themselves through it. And so those are the two different modalities that were evaluated. And the facilitators that led the in-person workshop groups are all Syrians living in Za’atri, who are volunteers with the organization.

And they’re trained in the delivery of the field guide. So the idea is that it’s this peer to peer. It’s people who are living in the camp, who are working with people in their community to deliver this intervention.

Sizek: So how did you become involved with this Beyond Conflict Organization? And what was your role and relationship to them while you were conducting your research?

Herman: Yeah. So the Beyond Conflict actually met when I was an undergrad. They used to be housed at Tufts where I went to school. And I’ve worked with them for many years. They’re an organization based in Boston that applies concepts from neuroscience and cognitive science and psychology to study of peacekeeping and post-conflict contexts.

And they developed this field guide, which was developed by Mike Niconchuck, who was the program director for trauma and violent conflict at Beyond Conflict. And basically, they were looking to have The Field Guide for Barefoot Psychologists, which is this peer to peer psychoeducational intervention, which was developed in the context of Za’atri refugee camp to be used as a mental health care intervention with Syrian refugees living in Za’atri camp.

And so they had developed this field guide, and they wanted it independently evaluated, so they could understand the impact that it was having both on mental health outcomes and on these secondary level social stability outcomes.

And so the research team that formed was Vivian Khedari, who is at the New School for Social or she was at the New School for Social Research at the time. She’s now at Montefiore in New York. And she was the PI leading the part of the evaluation on the mental health outcomes themselves.

And then I was the PI that was working and looking at the secondary outcomes, so looking at these social and political implications of changes in trauma related distress that were reduced by the field guide and how they in turn impacted social stability in the context of the camp.

And so all of us together worked on this. And then the field guide was actually implemented in the field by [INAUDIBLE], which is a social development organization that’s based in Jordan and has offices in Za’atari. They work directly in Za’atri, and they have Syrian refugees who volunteer, who live in the camp.

And they recruited and trained Syrians who are living in the camp to be the facilitators for the project, for the field guide intervention. And so that was the team that worked together on this project as a whole. So there was Beyond Conflict, who developed the intervention itself, [INAUDIBLE] who implemented it, and through whom the Syrian facilitators who had been linked up with [INAUDIBLE] for a long time were recruited, and then myself and Dr. Khedari, who were the PIs of the evaluation itself.

Sizek: Interesting. So as you described this intervention, I think one of the things that I’m curious about is the history of this intervention and of the barefoot manual. So was it developed specifically for refugees who are dealing with trauma? Or what are the groups of people who it’s supposed to serve?

Herman: Yeah. So this was the first piloting of it. And this was the context in which it was developed. The idea is that it can be applied in other contexts. And the way that it would be applied in other contexts is the science would stay the same and the topics covered would broadly stay the same, although maybe there’d be different ways in which they were framed or talked about. But then the narrative would be changed to fit whatever context it was being administered in.

So you would not follow a brother and a sister fleeing conflict in Syria. You might follow a brother and a sister coming to the southern border of the United States and seeking asylum or whatever sort of context in which the intervention would be administered.

The story would be made and written with partners that have experience in that context or have lived through those experiences itself. So Mike Niconchuck, who was the lead author and the mastermind behind the field guide, he worked in the camp extensively for many years before writing the guide and worked in close partnership with scientists and people who are living in the camp and mental health care practitioners from the region and a host of stakeholders who had different perspectives on what care was accessible, what care wasn’t accessible, and really developed this to meet a need that he saw existing in this context.

And a lot of the story, the story of the brother and sister is sort of a composite of different stories that had been shared with him by people, by Syrians who were living in Za’atri. And so these characters, it’s all based on real accounts and true lived experiences and then anonymized and turned into these composite characters. So it’s not directly speaking to any one individual.

Sizek: Yeah. And so you mentioned that often mental health care isn’t really accessible in these refugee camps or in other locations that you might be studying. So what are the sorts of forms of health care and mental health care that people can access or that might be available to them prior to the advent of this field guide or other potential interventions?

Herman: Yeah. So I think the landscape of this has changed a lot in the past even five years, because I think there’s been an increasing acknowledgment that mental health is important. It relates to a lot of other things. And when it’s left unaddressed, it can have physical health implications, it can have implications for security, for community well-being and cohesion.

And so there’s an increased desire to have access to mental health care. That being said, there’s logjams in many of the service provision areas. So whether or not there are enough trained psychologists and psychiatrists, whether or not the modalities that people are trained in, so whether or not individualized therapy is a modality sense in the context of a refugee camp where there are 70,000 people and maybe there might be a lot of stigma associated with going and seeing a psychologist or a psychiatrist.

And so making people being able to actually seek out mental health care like that and sit down and not face any kind of shame or stigma for looking for those services is a real question or is important to consider in a lot of these contexts.

And then also if you’re in the context– if you’re in a context like the US and there are refugees that are resettled here, whether or that are actually mental health care services that are provided in the language that is needed or whether or not people have time in their work schedules to be able to access and either before COVID travel to a place where they can receive mental health care or engage with it virtually at this point.

So all of these things, I think, are important, very logistical, practical questions to consider. There are great data on how few actual trained mental health care providers there are in different countries and what the reported need for mental health care services are.

So I think there’s a real desire to develop more of these scalable peer to peer kinds of interventions where it doesn’t require someone that’s gone through some– it doesn’t require someone who has a clinical psych degree to provide whatever the intervention is.

It can be provided safely and ethically with people that have received training and then having that sort of provision of this peer to peer intervention be plugged into a broader professionalized mental health care system. So that if people do experience really adverse reactions to whatever intervention, that it goes beyond what the intervention can provide.

And they can seek professional care if it’s needed. And I think that that’s something that is really carefully considered in a lot of these programs and definitely has come up in all of the conversations and programs that I’ve worked on or worked with and making sure that these escalation protocols are in place and are functioning.

Sizek: Yeah. So I mean, I think one of the things that this brings up for me is this question about the site specificity of these kinds of programs. You both want to have a program that might be scalable and that you might be able to transport between these different locations. But at the same time, Za’atri is a very specific setting.

So I would love to hear a little bit more about the setting of the refugee camp, who lives there, when did many of them arrive, do the people who live there share common backgrounds. What’s the situation at Za’atri?

Herman: So Za’atri refugee camp opened around 2012 and most people arrived in 2013. For example, in our study, about 65% of the sample arrived in 2013 and then about 30% arrived prior to that. And the rest arrived sort of in the year after.

Most people made the journey from Syria with friends or family. Nobody that we surveyed had made the journey alone. And most of the people that are living in Za’atri come from the southern region of Syria, which makes sense because the camp is situated right on the northern Jordan, northeast Jordan, seven kilometers from the border, I think that’s the number, with Syria.

And I think that’s something that it’s been in operation for a long time. People have lived there for– it’s 2021 right now. People have been there for seven, eight years. And I think that in recent years, there’s been more of an acknowledgment that this is more of a– people need to be able to establish roots in a home there.

So I remember over the course of the time that we were working there, there was a change, and people were allowed to plant trees. Prior, people weren’t allowed to plant trees because it was seen as a sign of permanence. Or people were able to start modifying the shipping containers that constituted the living shelters. And that, again, was a sign of more permanence.

There was a sewage system that was installed and sanitation after– I can’t remember exactly the year, but it was not in the first few years. And again, these are indications of more permanence. So I think, though, it’s a refugee camp, I think that it’s seen as home.

And it’s home to 70,000 Syrians. And it’s the largest refugee camp for Syrians in the world. And I think that as a community, there’s a lot of different international organizations and NGOs that provide services there. And I think that thinking about the ways in which people interact with different institutions, it’s a setting that’s very regulated.

You have to have work permits to be able to leave to work. I know that when we were doing facilitator trainings, we had to get specific permission to be able to hold trainings site. And I think that thinking about what it means to live in a context like that continually and be able to find and make a home, those are questions that relate to mental health and community as a whole as well.

Sizek: Yeah. So I mean, one of the things that you just noted and this is true of many refugee camps is that they’re sort of assumed to be impermanent and then end up being rather permanent. But one of the things that you’ve noted in your research is that not many people do research on refugees, and instead they’ll do research on folks who have experienced trauma and then been able to either stay at their home or return home.

So what’s sort of different about doing this approach where you’re studying refugees who have had to leave their home and establish a new home elsewhere?

Herman: Yeah. I mean, I think some of that is practical limitations. It’s hard to access populations that are in refugee camps, especially if there’s, what I just referred to, there’s a lot of regulations. And there’s a lot of barriers to entry, all for good reason. But it’s a different context to work in. And I think in these contexts, it’s incredibly important to have the research team following whoever the field partner and the implementing partner are.

And that we are working in service to whatever the goal of the project and the implementers are for whatever population is being served and in terms of our work is in service to them in many ways. And so I think in thinking about the differences between populations that have stayed and those that have resettled either in camps or outside of camps, I think that there’s a lot of open– in the literature, there’s a lot of questions about maybe there’s a purging of less social individuals.

Those are the people who have left. Maybe there’s an element of post-traumatic growth among those who stayed. There’s an intense bonding of going through a collective trauma together, whether we’re talking about conflict or a natural disaster, anything that would cause economic inequality or insecurity, anything that would cause people to seek a different place or to be forced to flee.

When you think of traumas like that, the people that have remained in their community or have returned to their community might be systematically different in some way than the people that left. I think it’s an open question, and I think it depends on the context.

I think it’s not like broadly generalizable about why people leave. And I think that one thing that was– one thing that is important to note, though, is that in any context in which people have fled their homes and are resettling somewhere else, it’s important to understand the ways in which the underlying social networks either are still accessible to them or are no longer accessible to them.

So there’s been a lot of work on the importance of mobile phones and people staying connected to their social networks back home after they’ve fled or resettled somewhere. I think in Za’atri camp, for example, because a lot of people are from the same region, there’s not necessarily– there’s a different set of challenges from if there’s a group of people who are resettling in a city where they’re very clearly outsiders in a new place.

And so I think it just depends on what the context is and how the individuals who are resettling somewhere or are trying to make a home somewhere, how their identity relates to the identities of everyone that they’re surrounded by and the identities of the people that they are no longer in close contact with physically at least.

So I think those are some of the questions that came up in the work and that were continually– I made sure to continually think about and talk about with my research partners and the field and implementing partners.

Sizek: Yeah. So one of the things that you were trying to measure in your research, from my understanding of it, is exactly this relationship between individual people and the traumas that they may have experienced and how that relates to this broader social setting.

So you’re really interested in social stability. So can you just help us understand what social stability means to a political scientist?

Herman: Yeah, totally. So I think that to take a step back, the broader research question that I’m interested in is the ways in which the psychological implications of living through trauma impact different factors that relate to an ability of a community to be able to cohere and to be stable in the aftermath of conflict and forced migration.

So to break that apart into its different components. When I’m talking about trauma or trauma exposure, I’m talking about any kind of event that threatens a person’s physical integrity or well-being in a way that might be a threat to their life or to their physical injury.

So this can be things like experiencing some kind of violent attack or witnessing a violent attack. It could also be learning about some kind of harm or death of someone who you love or a friend. So it doesn’t have to be only something that happens to yourself.

If there’s a sudden event that happens and you learn about it, that can be considered a traumatic exposure. And then I look at the psychological implications of that. So any kind of trauma related distress that can develop in the aftermath of that.

So that might be something like PTSD, or some kind of anxiety syndrome, or some kind of emotional dysregulation that might develop. And then what I’m really interested in is how that trauma related distress in turn affects social stability, which I define as these kind of individual level attitudes and behaviors that connect to key interpersonal and sociopolitical dynamics.

So these are the outcomes that political scientists are really interested in. So things like prosocial behavior or intergroup dynamics, political participation, all of these things that indicate how an individual is connecting with their community, the institutions in their community, how they are forming connections that allow either broad based stability or not.

And I think that understanding how and why mental health impacts these things is something that I saw as a whole in the literature. There was sort of an understanding that living through violence, living through conflict has some impact on the way that communities rebuild or exist in their aftermath.

But testing those specific mechanisms, how do we get from experiencing some kind of trauma to having it affect the people that live through it? And so I’m really trying to precisely isolate some of these underlying mental health implications that I think do often have a huge impact on the way that communities cohere or don’t in their aftermath.

Sizek: Yeah. So one of the things that seems really interesting to me is that this social stability category, it’s really made up of a lot of complex factors. And this seems like something that would be really challenging for someone to measure.

So for something like prosocial behavior, first, how would we talk about prosocial behavior? And then how do you even try to measure something like that?

Herman: So this is a great question. This is actually part of a– I have another project related to my dissertation work that’s a collaborative project with Justine Davis, who was at Berkeley in the political science department and graduated and is now at Michigan as an LSA collegiate fellow.

And she’s going to be starting as an assistant professor next year. And we are doing this systematic review where we’re looking at– we cast a very wide net. And we gathered all the studies that are looking at either the impact of trauma or violence or the subsequent mental health implications of trauma and violence.

So things like PTSD and anxiety and depression. Any of those studies that looked at either the exposure itself or the responses to the exposure and then how they in turn impact different social and political indicators. So through that work, I did this broad based survey of all the literature and all the different ways that we define these social and political outcomes.

And there’s certain sort of measures that are used commonly. They vary across contexts as they have to, but these concepts of pro-social behavior, what does that actually mean and how do we actualize that? Things like group membership, so how often people are attending certain group meetings or willingness to interact with other people in institutional settings.

It could be things like in other contexts, people have sort of seen it more as an altruism, as defining it as altruism. So willingness to help other people out. Some of the more common questions are like, if you see a wallet sitting on the ground, how likely– or if you leave your wallet on the ground, do you think someone in the community is going to pick it up and return it to you?

And so the process of taking these concepts and looking at concepts that are of interest in the literature as a whole and then translating them and having them make sense in the specific context that we were working in in Za’atari was a process of I took a bunch of different ways of measuring these variables and concepts, and then I brought them and worked with the field partners and piloted them to make sure that they made sense.

So for example, some of the measures of peace and reconciliation attitudes that were really of interest in the literature were totally nixed in the context that we were working in, mostly because they were deemed as really insensitive. And they didn’t make sense because in most people’s mind, the conflict was still going on and it was not either practical or kind to ask about resolutions to it.

So a lot of the times, it was a matter of taking the way that these things had been conceptualized in the literature and figuring out how they translated in the specific context that I was working in. So in this specific study, I defined prosocial behavior as the two, as both group membership and then perceived communal security.

So the idea that someone felt connected to their community and was willing to engage with their community.

Sizek: Yeah. So what would be an example of a kind of group membership that you would measure? Would you see if someone is going to religious services every week? Or are there sorts of clubs or organizations? What are the sorts of organizations that you look to for these measurements?

Herman: Yeah, totally. So not whether or not– we ask separately whether or not how people connected with their religious identity. And that was another measure that the classic measure as it had been used in other surveys did not make sense.

And we had to pilot a different way of defining it. For group membership, we basically brainstormed a list with all the field partners of all the different kinds of groups and associations that people could be engaged in. So things like that– the classic list that you would think of is like sports team, arts group, maybe some kind of educational committee, like a PTA and some kind of advocacy group.

But there are things in Za’atri camp that I would not have guessed like a water committee and a volunteer committee. And so there was all these very contextually specific definitions that you really have to be working with people who have a lot of context specific knowledge to make sure that all of the different ways in which you’re operationalizing and measuring things make sense in the specific context.

Sizek: Yeah. I guess another aspect of this is it seems like it’s something that’s really ripe for longer term research. Do you have plans on continuing your research at Za’atri and trying to figure out the longer term implications, both of the intervention that you’re studying as well as just how these intergroup relationships or pro-social behaviors might be changing over time?

Herman: Yeah. That is a really important part of this work because I think that a lot of the time, mental health is sticky and it’s also not linear. So you take a snapshot measurement of it with one round of data collection and it can change.

And it can also– maybe you do an intervention and in its immediate aftermath, you don’t see any effects. But three months down the line, different outcomes actually improve. So I think that we did one follow up that was three months after the last week of the intervention. But three months obviously isn’t that long.

We were hoping to do semi-structured interviews with people in the coming another three months or a year after that and then COVID hit. So we haven’t been able to do that. But the field was still very closely connected to the field partner. And so it would be great to be able to continue to follow up in some way

Sizek: I guess and this is also a question about this longer term implications of this research and thinking about the application of it elsewhere. Because you were mentioning that you’re hoping this intervention might be scalable or be used elsewhere. Do you have plans for testing it out or finding new research questions using this same intervention elsewhere

Herman: So Beyond Conflict is working on developing other versions of the guide to be used in other contexts. And they also have been working on developing an app to be able to deliver the intervention remotely. So being able to have people– and they are piloting it with an online course that people can sign up for and walk themselves through the guide and interact with it in that way.

So there’s a whole bunch of different ideas of ways in which the field guide could be delivered, both in person and other contexts and also through an app or through an online modality. And I think that the thing that I think is broadly applicable in thinking about these more peer to peer mental health and psychosocial interventions is getting creative about how can people engage with these things and what ways can it fit into their lives and what are the ways in which people are most likely to– how can the information and the resources be provided in a way that’s as useful as possible?

And I think that one thing that has been interesting to think about with COVID is that people are much more comfortable with interacting with different kinds of trainings and doing education virtually. And so I think that has lowered some of the barriers to entry in terms of getting people to buy in to, let’s say, a 12 hour course online.

That’s something that people are much more used to engaging with. Whether or not people want to stare at their screens anymore right now is an open question. But I think that, A, there have been better platforms for delivery that have been developed during COVID. And people are more used to engaging with those platforms. And I think that that’s really useful and lowers a lot of the costs and barriers to entry.

Sizek: Yeah. A couple of weeks ago actually on the podcast, we had two scholars, Hannah Zeavin and Valerie Black, come in. And they actually talked to us about the history of chat bots and the history of mental health chat bots.

And one of the interesting things that they shared was that during COVID, the barrier to entry for a lot of these mental health care– I guess, mental health care through the internet, the barrier to entry has gotten a lot lower and a lot of the bureaucratic realm of how health care works and HIPAA compliance, all these things were lifted.

And they’re both concerned that once COVID is over, that there might be a lack of access to care. But also, some of these regulations, just like the regulations that you’re talking about for doing research at Za’atri, those are also there for a good reason.

So it’s a real balancing act of trying to figure out when these applications can be helpful to people without being all, I guess, extremely techno optimistic about their implementation.

Herman: Totally.

Sizek: Yeah. So I guess just in thinking about the broader implications of your research, one of the things that I would love to hear a little bit more is how you think that this intervention that you’ve been measuring, how this might be used for future policymaking, specifically for refugees, since that’s the group that you’ve been studying? How do you think that this might be implemented at broader levels for policymakers rather than just at the community mental health level?

Yeah. So I think that there’s a lot of different ways of thinking through the implications of mental health in post-conflict and forced migration settings. And I think that one thing to consider is at what point is our mental health needs addressed.

And I think that one of the things that is growing in consensus is that it can’t be this thing that can just be shoved aside until everything else is stable. Obviously, there are needs that have to take precedent. So food, and water, and shelter, and hygiene, and physical ailments. All of these things have to be addressed often immediately in the aftermath of a crisis.

But I think that what ends up happening is that sometimes mental health can be thought of as not even just a second order need but a third order need. So it’s like, well, once we get people back in school and we get people jobs and we get them reconnected with their community, then we can address the individual mental health issues.

And I think the thing to think about when thinking about the utility and the importance of any kind of mental health intervention is understanding that individual mental health challenges can serve as an impediment for people being able to engage with education, engage with their livelihood, engage with any kind of community building exercise or rebuilding political institutions in a community that when individuals have any kind of trauma related distress or they have any kind of psychological distress, that might be a factor that’s keeping them from being able to engage.

And I think that there’s a– the UN put out a statement in or a directive in 2019 indicating that mental health and psychosocial care should be better integrated into peace building efforts. And I think that those sorts of directives are an acknowledgment that it can’t just be put on the back burner and we can’t just wait to deal with it until everything else is addressed.

So I think that– but then the other hand of that is that mental health care can be expensive and there could be barriers to entry or there could be stigma associated with it. So how can you square these two things and that there’s this acknowledgment that mental health and psychosocial care should be more broadly accessible?

It is imperative to rebuilding communities and helping social stability in the aftermath of conflict and forced migration. But it cost a bunch and there’s stigma associated with it. And we might not have enough trained mental health care professionals to actually provide services safely.

And so that’s where I think some of these more peer to peer low cost interventions can come in. And that’s also why I think it’s important for them to be evaluated in a rigorous way and independently. So I said that we’ve worked very closely with the field partners, but the research team was in charge of the survey design.

We were the ones in control of the data. And so it was an independent– we were working collaboratively, but it was an independent evaluation. I think that understanding the ways in which these interventions work, do they have adverse implications, how do you need to embed them into professionalized mental health care structures, I think that these are all questions that are important as these programs become more widespread.

But I think that there’s a real power to these programs. The field guide was based off of a similar guide that was developed for medical care, for not for physical health care called Where There is No Doctor, which was basically a book that trained not medical professionals and how to provide very basic medical care in contexts where there’s not a lot of access to doctors.

And so things like wound care or water, any kind of very basic medical care. And it was really effective because empowering people to be able to provide basic services to the people that they live in a community with is a really powerful tool and making sure that it’s context specific and people have access to more professionalized care if they need it is also an important part of that.

But a lot of things can be addressed at these more peer to peer levels. So I think that that’s where these interventions– that’s the need and the hole that these interventions can fill is that if there are more people who need mental health care support than the whatever medical systems can provide, then these community based health care, mental health care provision or these community based mental health care interventions can actually fill that need.

And I think that evaluating them and understanding the way that they work and potential ways in which they could have adverse effects and how you can address those effects is an important part of it as well.

Sizek: Yeah. Well, I hope that you will be able to continue to do this kind of evaluation of these new tools in your future research. Thank you so much for coming on the podcast.

Herman: Thank you for having me. I really appreciate it.

Woman’s Voice: Thank you for listening. To learn more about Social Science Matrix, please visit matrix.berkeley.edu.

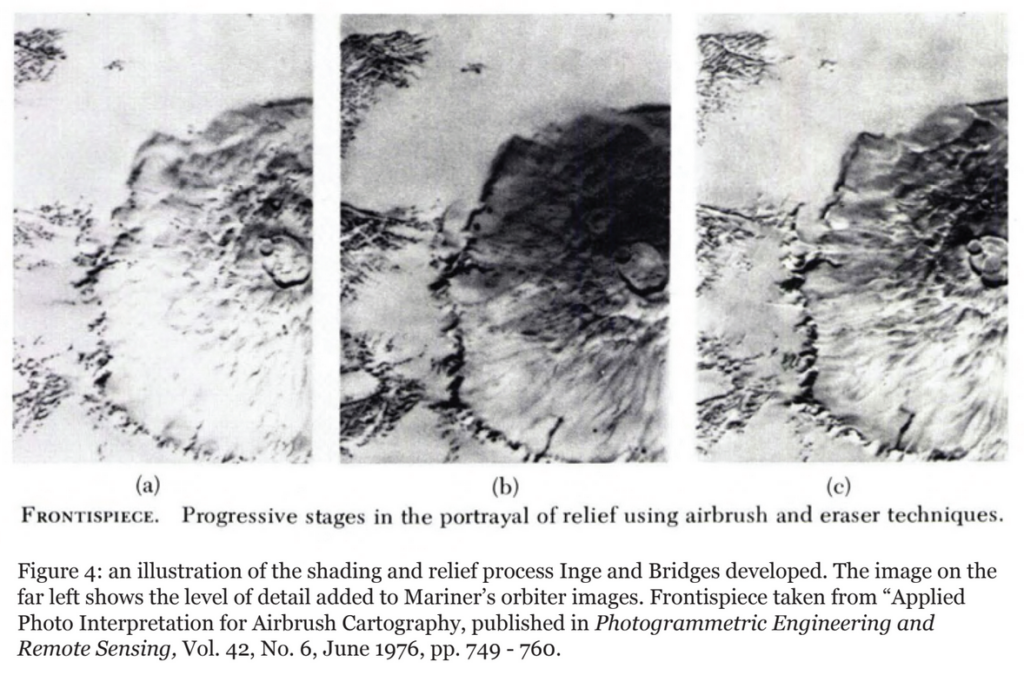

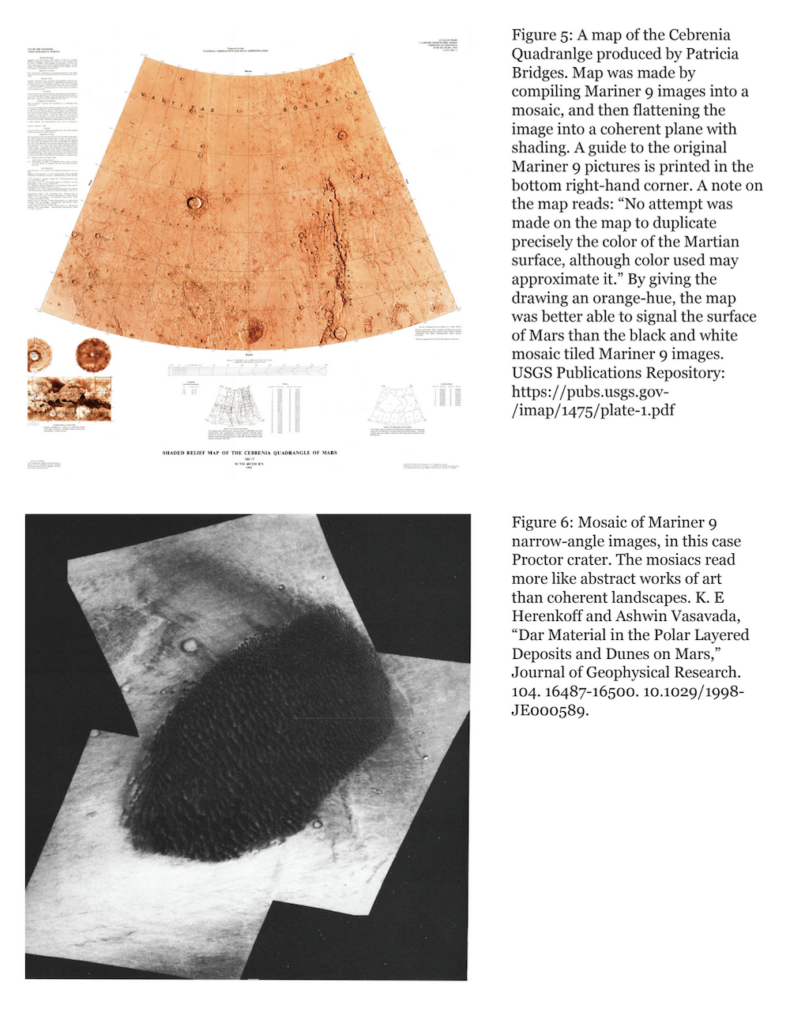

The Mars mapping efforts of the early 1970s — the maps we made with Mariner images — were actually made with a set of techniques developed in the 1960s for mapping the lunar surface in preparation for Project Apollo. In the early 1960s, photographing the Moon with high enough resolution for effective mapping was fairly difficult. The solution was to hire artists to come in and bolster the resolution of fuzzy photographs by hand with an airbrush. Patricia Bridges refined the technique of airbrush editing at Lowell Observatory, and trained a whole roster of illustrators in the process. She used a lot of the same techniques again in the 1970s to make clearly legible drawings of the Martian surface.

The Mars mapping efforts of the early 1970s — the maps we made with Mariner images — were actually made with a set of techniques developed in the 1960s for mapping the lunar surface in preparation for Project Apollo. In the early 1960s, photographing the Moon with high enough resolution for effective mapping was fairly difficult. The solution was to hire artists to come in and bolster the resolution of fuzzy photographs by hand with an airbrush. Patricia Bridges refined the technique of airbrush editing at Lowell Observatory, and trained a whole roster of illustrators in the process. She used a lot of the same techniques again in the 1970s to make clearly legible drawings of the Martian surface.