What are the impacts of reparations on the lives of victims of violence? Arlen Guarin, a PhD Candidate in Economics at UC Berkeley, studies the effects of policies that aim to reduce poverty and inequality, including reparations given to victims of human rights violations in Colombia.

His research draws upon tools in applied econometrics to identify the causal impacts of various policies by linking large administrative datasets that capture information on a broad range of outcomes, including labor market outcomes, consumption, health, and human capital formation. His research uses careful analysis of administrative data to demonstrate how unrestricted reparations improve the lives of recipients.

For this interview, Matrix content curator Julia Sizek asked him about a working paper that he developed with Juliana Londoño-Vélez (UCLA) and Christian Posso (Banco de la República).

The internal armed conflict of Colombia, which has included a prolonged conflict between the FARC-EP (Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia-People’s Army) and the government, has been a central part of Colombian politics since the 1960s. Can you describe the history of the conflict, and how the Colombian government decided to address the effects of this conflict through a reparations program?

Colombia has had a very long internal armed conflict, the most prolonged in the Western Hemisphere. In the mid-1960s, some left-wing rebel groups like FARC-EP and ELN (National Liberation Army) emerged in remote regions of the country. In the 1980s, the violence escalated as right-wing paramilitary groups developed in order to contain the emergence of left-wing guerrillas and protect landowners and drug lords who were involved in the increasingly profitable cocaine trade. This intensified conflict caused an increased number of attacks against civilians.

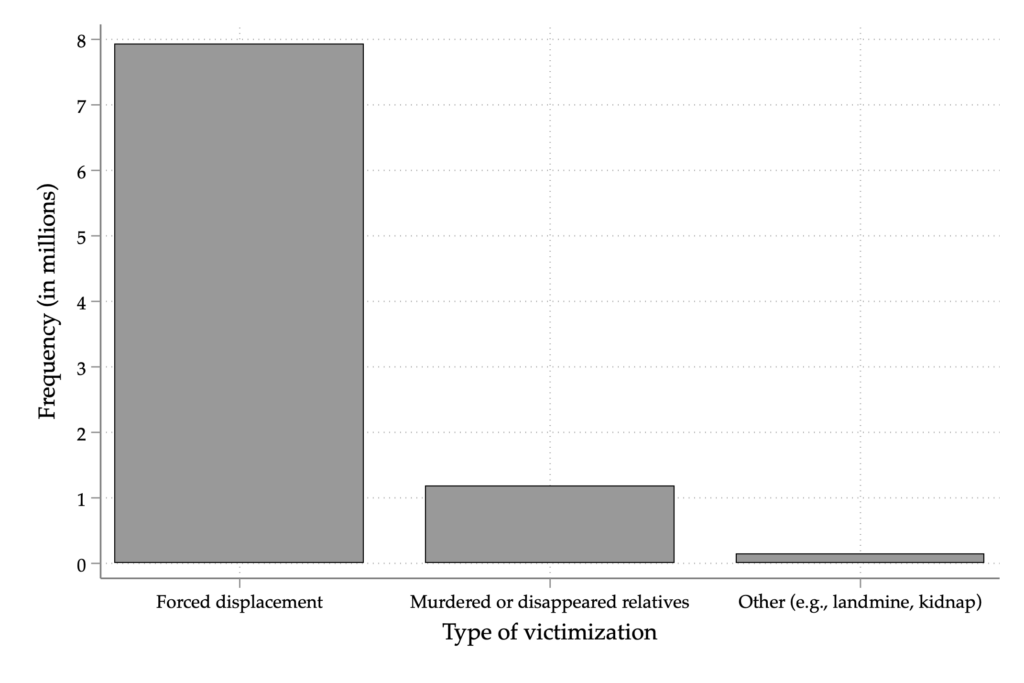

Between 1980 and 2010, the conflict claimed hundreds of thousands of lives, and almost nine million people were affected by the conflict. Attacks were widespread, with rural and poorer areas disproportionately affected by the violence. The majority of victims were forcibly displaced; the remainder had family members who were forcibly disappeared or murdered.

After a failed peace negotiation between the government and FARC-EP in 2002, violence peaked, as did victimizations of civilians. Following the peak, the number of victimizations decreased as Colombia attempted to transition toward peace and reconciliation. In 2005, Colombia demobilized paramilitary groups and reintegrated them into civilian life through the Peace and Justice Law. And in 2016, the government negotiated and signed a peace treaty with FARC–EP.

As part of its attempts to transition into post-conflict reconciliation, the government passed the Victims’ Law in 2011. Considered one of the world’s largest and most ambitious peacebuilding and recovery programs, the law seeks to award reparations by 2031 to 7.4 million individuals victimized by guerrilla, paramilitary, or state forces . (While approximately 8.9 million people were victimized, today only 7.4 million people are eligible for reparations, as some people are deceased or unreachable). In addition to providing reparations, the law aims to restitute dispossessed lands, award humanitarian aid to households in emergency conditions, and enhance access to micro-credit and subsidized housing.

The Victims’ Law has personal significance to me. I was born and raised in a rural Colombian town called Granada. When I was nine years old, the conflict dramatically intensified there. Bombings and massacres claimed the lives of many of my neighbors. Innocent people were routinely taken away for “questioning,” and we would later learn they had been murdered.

In 2014, I heard that some of my neighbors and relatives had received the reparation. Shortly after that, I arrived at UC Berkeley to start the PhD. I discussed the idea of studying the impacts of the Victims’ Law with one of my fellow students, Juliana Londoño-Vélez. We decided to work together on the project, and she encouraged me to start working on the necessary data.

Over seven million Colombians — more than ten percent of the population — suffered as a result of the conflict. Can you describe how the different types of victimization are being compensated through the 2011 Victims’ Law?

Almost one in five Colombians is a victim of the conflict, or approximately 8.9 million people. During the last three decades, nearly eight million individuals were forcibly displaced, and 1.2 million people had their relatives murdered or forcibly disappeared. Thousands of others were raped, kidnapped, tortured, injured by landmines, or forcibly recruited as minors.

The Victim’s Law aimed to award reparations to the nearly 7.4 million who registered as victims. Victims included those who suffered forced displacement, homicide, forced disappearance or kidnapping, rape, injury from landmines, or other injustices. For those who died or disappeared during the conflict, their family members were awarded in their stead. The law also defined the size of the reparations and indexed them to the monthly national minimum wage (currently $250 USD), a figure that changes each year. Reparations to victims or their families are delivered at the household level. The size of the reparation depends only on the type of the victimization, with victims whose relatives were murdered or forcibly disappeared receiving 40 times the minimum wage – approximately 10,000 USD – and victims of forced displacement receiving 27 times the minimum wage.

The amount of money is often sizable for the receiving victim, especially since many Colombians earn below the minimum wage. For the population we study, the average reparation represents more than six years of income and thereby has the potential to improve victims’ wellbeing in the long run. The goal of our research project was to understand whether this money could help undo some of the socioeconomic gaps induced by victimization. For example, could it help victims find better jobs? Could it improve their health? Could it increase the educational opportunities available to their children?

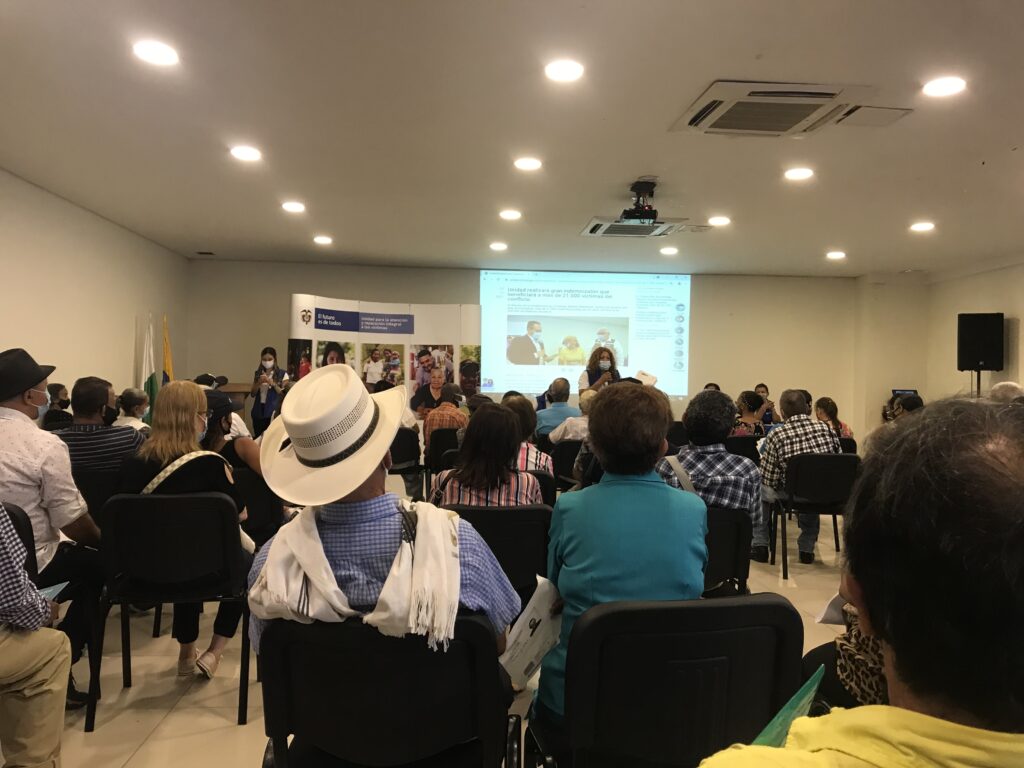

This image shows one of the victim reparation meetings, in which victims are informed that they are going to receive reparation payments. How has the reparations process been run at the state level, and how are victims informed about when they will receive their payments?

The Victims’ Law created the Victims’ Unit, a government-run agency that has been in charge of the administration and delivery of reparations. Despite being logistically and operationally managed from Bogotá, the capital of Colombia, the Victims’ Unit has more than 30 regional centers and hundreds of contact centers around the country, where the final details of the delivery of the reparations are coordinated.

From the victims’ perspective, the process of receiving the reparation is as follows. First, they receive an unexpected phone call from the Victims’ Unit. The caller instructs them to attend an “important” meeting at a specified time and location but does not mention a reparation. At that time, some victims may suspect that they are going to be given the reparation since they may have learned from others’ experiences, but the timing of the call itself is unexpected.

A few days later, the victim arrives at said meeting, usually at one of the regional centers. During the meeting, the victim is informed that they will receive reparation and is given a letter. The letter formally acknowledges that the victimizations never should have happened and describes when the reparation check can be collected from Banco Agrario, Colombia’s state bank, which is usually 1–2 weeks later.

Because of the large scale of the program, reparations were not paid all at once. How were you and your coauthors, Juliana Londoño-Vélez and Christian Posso, able to use the timing of the reparations to understand the causal effects of these payments?

We used microdata from the universe of registered victims, a unified and centralized registry covering the more than eight million individuals who reported being victimized during the Colombian internal conflict by August 2019. We linked the victims registry to eight other national administrative data sets containing information on formal employment, entrepreneurship, access and use of formal loans, land and homeownership, health care system utilization, postsecondary attendance, and high school performance for all members of the victims’ households.

Our final dataset has information on millions of victims eligible to receive the reparation payment and a comprehensive list of outcomes observed before and after the arrival of the payment. These types of data, in which the outcomes for the same individual can be observed over time, are called panel data sets.

Importantly for us, due to government budget and operational constraints – you can imagine the constraints associated with compensating one in seven Colombians – the rollout of the reparations program was staggered over time. This feature, together with the fact that the arrival times of the payments were unanticipated, have allowed us to identify the causal effect of the reparations using an empirical econometric approach called an event study.

An event study is a methodology that is used in contexts when the implementation of the program that is subject to be evaluated occurs over time rather than at once (staggered adoption), and where we can observe individuals and their characteristics at different points in time (panel data), as in our case. Intuitively, this methodology compares outcomes for victims who have received the reparation to those who have not yet received it. By comparing outcomes between these groups, we are able to isolate the causal impacts of the program on victims’ long-term outcomes.

This image shows an educational fair in which the victims are taught about how to use their reparations. How does the Colombian government view reparations as a tool for development?

The government presented reparations to victims as seed money to transform their lives; specifically, they suggested that the victims use the money to invest in productive activities, such as postsecondary education, business creation, or housing, which could improve their families’ long-term wellbeing. By presenting the reparations in this way, the government was treating reparations like “labeled” cash transfers, as they suggest that victims invest the money in specific activities.

In line with this purpose, the government held fairs to connect victims with local public and private institutions providing investment opportunities in education, housing, land, and small businesses. Victims could also voluntarily participate in investment workshops, where they would receive training in budgeting and investing, including getting help to obtain small business or student loans and pay off old debts .

The government also used the reparations to recognize the harm suffered by victims. The letter received at the time of the reparation also includes a dignification message about what the reparation means that reads roughly as follows:

“As the Colombian State, we deeply regret that your rights have been violated by a conflict that never should have happened. We know that the war has differentially affected millions of people in the country, and we understand the serious consequences it has had — it is impossible to imagine how much pain this conflict has caused. However, from the Victims’ Unit, we have witnessed conflict survivors’ capacity for transformation over these years. We have witnessed their spirit to keep going, their strength to raise their voices against those who have wanted to silence them, their ability to rebuild their lives… For this reason, with your help, we are working so that you can live in a peaceful Colombia since it is the victims who actively contribute to the development of a new society and a better future.”

As you mention in the previous answer, the Colombian government treats these reparations not only as a recognition for harms suffered, but as a means to raise the standard of living. How do the insights from this case help us understand poverty reduction and basic income programs, and how does this differ from previous research on the topic?

The literature on reparations has largely consisted of qualitative work by political scientists, lawyers, sociologists, and other experts on transitional justice. We differ from prior approaches by offering one of the first known quantitative studies of a large-scale reparation program, in which we exploit rich existing administrative-level data on millions of victims of the conflict in Colombia to provide evidence on the causal effects of the reparations.

We also contribute to the literature on the effectiveness of cash transfers for poverty alleviation. Despite sharing similar features, Colombia’s reparations differ from the traditional version of those programs in two ways. First, the average reparation is over three years’ worth of household income and, therefore, substantially larger than most unconditional cash transfers. Second, reparations target victims of human rights violations, a uniquely vulnerable population. Adverse shocks in conflict settings, like forced displacement, can have lifelong detrimental effects and trap victims in poverty. We show that by providing households with a large, lump-sum grant, reparation can serve as a “big push” policy for the victim to transform their lives and escape poverty traps.

In this chart, we see how the reparations changed the lives of conflict victims. What were the effects of these reparations, both economic and non-economic, and what does this mean for thinking about reparations and universal basic income programs more broadly?

We divide our results into three sections: the impacts on work and living standards, health, and human capital accumulation.

For impacts on work, we find that reparations only have an economically small effect, with the money allowing victims to improve their working conditions, earn more money, and create more businesses. We also find that reparations increase victims’ consumption and wealth, as it allows them to buy a home or more land.

We also find that reparations cause an economically meaningful decrease in health care utilization. Victims are less likely to visit the emergency department, less likely to be hospitalized, and have fewer medical procedures after receiving the reparation. These findings are consistent with improved health due to better working and living conditions stemming from the reparation, findings that are novel in light of the inconclusive evidence for the impacts of money on the use of health services and physical health outcomes.

Finally, we find that reparations close most of the intergenerational educational gap caused by the victimization. Victims frequently use reparations to enroll in and attend college for the first time. They also improve the high school test scores of the younger members of the households, an effect that is not explained by changes in the high schools that they attend. In the study, we conduct a back-of-the-envelope cost-benefit analysis that shows that the gains from reparation outweigh the monetary costs. This makes them both a progressive and efficient policy tool to promote recovery and development.

Overall, our findings suggest that reparations programs improve long-term wellbeing along many dimensions. My hope is that this research can inform governments that are considering ways to heal the wounds induced by human rights violations.