On September 21, UC Berkeley Public Affairs presented a panel discussion focused on the proliferation of disinformation and what can be done about it. Social Science Matrix helped organize this event, which featured a group of preeminent scholars from across the UC Berkeley campus. The write-up of the event below, “Can we thwart disinformation? Yes, scholars say — but it won’t be easy,” was written by Berkeley News reporter Edward Lempinen.

Rising death tolls from COVID-19, a mob attack on the U.S. Capitol, efforts to ban teaching of critical race theory — all of these recent attacks on public health and political values have been driven, in part, by aggressive disinformation. But while the costs are clear, UC Berkeley scholars said in a recent panel that there are no easy answers, even as disinformation threatens democracy.

In the latest episode of Berkeley Conversations, an elite panel of scholars described a range of potential solutions, from measures to strengthen old-school local news media to government regulation of titans like Facebook and Twitter. But there’s a critical obstacle: Efforts to directly block disinformation could challenge core American values, such as free speech and freedom of the press.

That’s the challenge facing a troubled American democracy — and that was the crux of the provocative, and sometimes impassioned, online discussion.

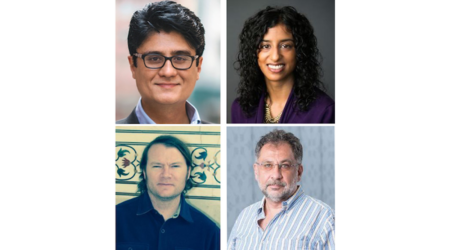

“The alternative to allowing the marketplace of ideas to work is to give the government the power to decide what’s true and false — and to censor what’s false,” said Berkeley Law Dean Erwin Chemerinsky, one of the nation’s leading constitutional experts. “I am much more afraid of that than I am of allowing all ideas to be expressed, even in light of the problems.”

Others, however, argued the threats to democracy have grown so acute that, without action, the First Amendment could be used to undermine the Constitution.

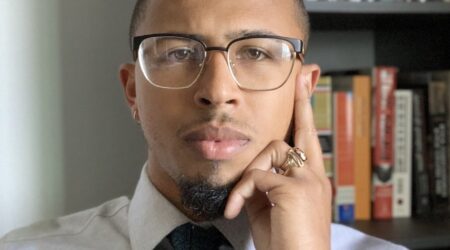

“It will be a real shame if democracy dies on the altar of free speech,” said Susan D. Hyde, chair of the political science department at Berkeley and an expert in democratic backsliding. The increasing frequency and intensity of disinformation “is not going to fix itself,” added john powell, director of the Othering & Belonging Institute. “It’s not clear to me that democracies will survive this, unless we do something very deliberate and very robust.”

Berkeley Conversations is an online discussion series that convenes world-class scholars to discuss a range of critical issues at a moment of historic challenge and instability in the U.S. and worldwide. Tuesday’s event, “Defending Against Disinformation,” was sponsored by Berkeley Law, the Goldman School of Public Policy and the Office of Communications and Public Affairs, with support from the Social Science Matrix.

Disinformation, in simple terms, is the dissemination of false information to shape political and social outcomes. It’s different from misinformation — and more malicious — because it is deliberately false. Not only does it contribute to our deep polarization, but, clearly, it costs lives and erodes democracy.

“I don’t think it’s hyperbolic to say these are existential threats to our society and democracy,” said Hany Farid, associate dean and head of the School of Information. “I don’t know how we have a stable society if we can’t agree on basic facts, because everybody is being manipulated by attention-grabbing, dopamine-fueled algorithms that promote the dregs of the Internet, creating these bizarre, fact-free alternate realities.”

Disinformation finds an audience — and influence — in a society that still suffers from racial and ethnic segregation, said powell. Research shows that in segregated societies, different groups don’t understand each other, powell said, and lack of understanding leads to exaggerated negative views of other group.

Plus, he said, research shows that U.S. segregation is growing worse, not better. In such an environment, those who peddle disinformation find a receptive audience. “Fear moves faster than a positive emotion,” powell explained. “If you’re trying to create fear, you have a huge advantage. If you try to increase hate, you have a huge advantage.”

That’s a social problem, powell said, but one that’s “hypercharged by technology.”

The power of disinformation is further compounded by the steep decline of conventional news media in the U.S., said Geeta Anand, the Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist who’s now dean of the Graduate School of Journalism.

Advertising revenue for traditional news publications dropped 62% from 2008 to 2018, Anand said. More than 50% of advertising revenue has shifted from traditional news organizations to social media. Of 9,000 publications operating in 1995, some 2,000 have closed.

“It’s expensive to train reporters to go out and report news, to check sources, to make phone calls, to check public records,” Anand explained. “Disinformation is cheap. … Social media companies are making billions, and news organizations are barely hanging on.”

In their 90-minute discussion, the scholars focused on two areas for reform that might check the advance and impact of disinformation: strengthening local journalism and finding ways to moderate the influence of social media, whether through social and financial pressure or through government regulation.

For example, panel moderator Henry Brady, former dean of the Goldman School, suggested a tax on Internet companies, with proceeds used to support local journalism. He also suggested aggressive efforts to break up massive companies like Facebook, in hopes that new and more socially responsible social media platforms would emerge.

But many proposals for containing disinformation collide with the requirements of the First Amendment.

The panelists focused particularly on Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act of 1996, which holds that Internet companies cannot be held legally liable for content posted on their sites by others. That protection was crucial for building the Internet and unleashing its vast power.

But changing that, and making the companies liable, would require them to review billions of posts a day, Chemerinsky said. Inevitably, they would block many more posts, with less than surgical precision.

On the right and on the left, “everyone wants to criticize Section 230,” Chemerinsky said. “I don’t see a better alternative.” Instead, he said, social media companies should be pressured to change practices and algorithms that lead them to allow and promote communication that is harmful, hateful and threatening to democracy.

Other panelists challenged that reasoning.

“The problem with disinformation on social media today is not primarily one of technology, but one of corporate responsibility,” Farid said. “We have been waiting for now several decades for the technology sector to find their moral compass, and they have not seemed to be able to do that. They continue to unleash technology that is harmful to individuals, to groups, to societies and to democracies.

“Left to their own devices,” he added, “that will continue.”

Farid and others acknowledged the need to balance interests and to work within the Constitution — but also argued that the moment requires urgent action.

“What we’re talking about is continuing to sort of dance the tango on a sinking ship,” said Hyde, co-director of the Institute of International Studies. “It’s just not working. … The Constitution is not going to matter on some level if we get to this really extreme worst-case scenario.”

Anand and others suggested that Berkeley could help to convene other universities and scholars to focus on solutions for disinformation and the challenges to democracy.

“I think Berkeley can do that,” she said. “We have the most incredible brains — legal brains, technology experts, public policy, government, belonging experts, journalism experts — right here on our campus. … There cannot be any area that we refuse to consider, or reconsider. We have to think outside the box. And we have to include the industry in helping us understand where the solutions lie.”