For this episode of the Matrix Podcast, Julia Sizek interviewed Morgan P. Vickers, an Assistant Professor of Race/Racialization in the Department of Law, Societies & Justice at the University of Washington. Vickers received their Ph.D. in Geography from the University of California, Berkeley, and their B.A. in American Studies, Communication Studies, and Non-Fiction Writing from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Their work has been supported by the National Science Foundation, the National Trust for Historic Preservation, and the Simpson Center for the Humanities. (This interview was recorded in Fall 2023.)

Vickers is currently a Content Editor for Environmental History Now and an Executive Board member of the Black Geographies Specialty Group of the American Association of Geographers (AAG). They previously worked with The Black Geographic, the National Trust for Historic Preservation, the Community Histories Workshop, A Red Record, and the Landscape Specialty Group of AAG.

The interview focused on Vickers’ research on drowned towns of the Santee-Cooper Project in South Carolina, wherein 901 families were displaced in the name of New Deal “progress.” Vickers’ work highlights New Deal infrastructures, transformed ecologies (notably, swamplands), and dispossessed (racialized) populations in order to challenge myths of universal progress and narratives of purportedly moral geographies.

Thematically, Vickers’ work contemplates Black ecologies, placemaking, federal dam and reservoir projects, racial capitalism, moral geographies, community memory studies, and questions of belonging.

Podcast and Transcript

Listen to the podcast below or on Apple Podcasts.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

Woman’s Voice: The Matrix Podcast is a production of Social Science Matrix, an interdisciplinary research center at the University of California, Berkeley.

Julia Sizek: Welcome to the Matrix Podcast. I’m Julia Sizek, your host. And today, our guest is Morgan Vickers, a PhD candidate in Geography here at Berkeley. Morgan is a National Science Foundation graduate research fellow and the Black Geographies Fellow at UC Berkeley.

Morgan’s work illuminates Black geographies and ecologies, placemaking, federal dam and reservoir projects, rural planning, moral geographies, the Black commons, and racialized underdevelopment in the New Deal. Thanks for coming on the podcast.

Morgan Vickers: Yeah, thank you for having me.

Sizek: So you trace this program that’s called the Federal Emergency Relief Administration, and more specifically within that, the Rural Rehabilitation Program, which later becomes part of the Resettlement Administration. This is already a lot of acronyms, but what does this program look like and why is it an important program to examine?

Vickers: Yeah, Yeah. So yeah, you’re exactly right. It is a mouthful. And I think that’s why scholars, and I think just general people, consider the New Deal kind of an alphabet soup. It is a lot of names and dates to keep track of. And I have them written in front of me so that I can keep track of them.

I’m studying the New Deal and the New Deal administrations, specifically because I’m offering what I think is a critique of New Deal progress, or this myth of progress that was sort of proposed by the New Deal. A lot of these administrations were sort of designed to rehabilitate the nation.

And in the South Carolina context, a lot of the rehabilitation was intended to transform the human — and often the racialized human — into a more productive citizen, a more productive farmer, and someone who would be in service of rehabilitating American capitalism, essentially.

And so that’s sort of the project I’m working on. And more specifically, in this chapter that we’re sort of chatting about, I’m focusing on how rural resettlement was a project of American rural development in American development as a whole.

Sizek: Yeah. So let’s sort of just dig into resettlement as a project and why resettlement versus other forms of aid. What was sort of the idea behind a resettlement project versus, for example, just giving people some money?

Vickers: Yeah, yeah. So in the South Carolina context, it was not an either/or situation. So in parts of South Carolina, they were offering different forms of aid. So this could be fiscal aid in the form of grants.

In several cases, the federal government, or state governments, brought people out of their homes that were— their homes and farmland that were seen as unproductive and sort of destroyed depleted soil. So they purchased these homes with the idea that these farmers, with whatever money they were given, could move into different properties.

So these people weren’t essentially placed into resettlement communities, but they were “offered,” and I use offered in quotations, a chance to move somewhere else where they could be more productive. But other forms of aid included seed grants, for example. They included tool loans, the construction of schools. It was essentially a lot of different things that would make communities more productive in a variety of different ways.

But compare that with resettlement — and I’m thinking resettlement here as specifically organized and planned communities that were often places, where families were often placed on meticulously designed lots on pre– in prefabricated homes — that was different.

And that’s of interest to me specifically because it wasn’t just about rehabilitating the farmer and rehabilitating his land, but also about rehabilitating the entire human.

So in these resettlement communities, they were placed amongst neighbors who were equally in service of the project of becoming better humans or becoming better financial contributors to the nation. And in these communities, they were offered— or they were sort of forced into positions where they had to undergo meticulous health observations. They had to go to school for a certain amount of time. They had to sort of complete quotas, agricultural quotas.

And some of these things were really positive. Like, these health surveys helped reduce malaria in communities, and some of these communities didn’t have schools before. But other portions were sort of in service of producing for the community and not for sort of the sake of your own family, the sake of your own happiness. And that’s sort of what I’m interrogating here.

What was the creation of resettlement community in service of and was it really in service or for the benefit of these individual farmers and their families and the types of lives they wanted to live?

Sizek: Yeah, so let’s dig in, and maybe we can talk about a couple of the resettlement communities that you look at. So how do you go from folks who are living on either their farms or in some town elsewhere, how do they get picked and then sort of plopped down into this new prefabricated community?

Vickers: Mm-hmm. The quote that I often use is meticulously vetted. So these families were vetted at multiple levels. And you had to meet a series of criteria in order to qualify for placement in these resettlement colonies. One of which is had to be a male under the age of 50 years old.

You had to undergo background checks where your previous landlords, if you weren’t a landowner or your previous employers, would sort of give character statements about you. You had to demonstrate that you were capable of paying off your loans.

That was the key sort of dynamic of this. You were not just supposed to be someone who contributed to a community, but someone who was able to sort of financially take care of yourself. And you were vetted at— I think I mentioned this. But you were vetted at multiple levels.

So you underwent a federal sort of background check, and then you underwent a state background check. And oftentimes there was a community leader, an overseer in some ways, who would do their own individual background check to make sure that you fit within the community.

And I mean “fit” sort of within the structure of the community, but also within the values of the community.

Sizek: And so given that there’s all these sort of extensive background checks, how do people and why do people choose to opt into these resettlement schemes? Because it seems like it’s not like the government is saying, hey, you, go settle into this other place. How do people opt in?

Vickers: Well, some people weren’t given a choice as to whether or not they had to be resettled into these communities. So right, my larger dissertation project studies the Santee Cooper Hydroelectric and Navigation Project. This was a New Deal project constructed between roughly 1934 and 1941.

And 901 families were dispossessed in the making of this project. The majority of these families, about 80 to 95 percent of them were Black. And a lot of these– I think, to the earlier question, a lot of these families were offered money or were relocated through eminent domain and were sort of scattered.

They were forced to figure out where to go. But a select number, again, those who met these criteria, these quotas and these qualifications, were “allowed,” and again, I use allowed in air quotes, to move into these resettlement colonies as they were called in South Carolina.

So they were moved into specifically Orangeburg Farms, one of the largest resettlement colonies in the state. It was the only interracial resettlement colony in the state, but they weren’t really given an option in that case.

They were told, you need to move off of your property because it is going to be flooded. It’s going to be inundated in this hydroelectric project. You can either go into this resettlement colony, or you can find somewhere else to live.

And the amount of money that a lot of these families, especially the Black families and especially the former tenant farmers who didn’t own property, it was a much better option for them to go into a planned community where they could, in theory, acquire the right to their own property at the end if they were to pay off their loans, rather than trying to find property on their own with the small amount of money they were given.

So I– at least from my understanding, a lot of these families weren’t really given an option. Just as the families who were resettled and not placed into resettlement colonies, a lot of them also weren’t given an option.

The government deemed their property to be sort of unfit for farming, unfit for human habitation. And it was sort of, get off of this property, go somewhere else, whether it’s with your family members in another state, onto a resettlement community if you qualified, or just get up and go somewhere else, essentially.

Sizek: Yeah, so you mentioned Orangeburg, which is one of the resettlement communities that you study. Can you tell us a little bit more about this site and what’s sort of interesting about Orangeburg in relation to the other resettlement communities in the area?

Vickers: Yeah, so– and for some background context, there were four total resettlement colonies in the state. One was Orangeburg Farms, one was Allendale Farms, one was Ashwood Plantation, and one was Tiverton Farms.

So Ashwood Plantation was the only all-White resettlement colony in the state. Orangeburg Farms was the only interracial resettlement colony in the state. And interracial is sort of loosely interracial because there was a dividing line between the White and Black populations. They called it a buffer zone.

But the other two resettlement colonies were all Black. And so originally, in the state of South Carolina, the state proposed having one singular 1,000-unit resettlement colony. Essentially, nowhere in the state was willing to accept 1,000 what they perceived to be destitute families.

They didn’t want to have that many impoverished people in their own community, and so they decided to scatter it into four different resettlement colonies. Originally, it was supposed to be six, but they reduced that number.

So how Orangeburg sort of compares to the other ones. A lot of these properties, a lot of these communities received sort of similar aid. So they received, again, prefabricated houses. They received seed grants. They received tools. A lot of homes were constructed— sorry, not homes. A lot of schools were constructed in these communities, recreational facilities, stores and businesses, et cetera. So there were all sort of given this baseline similar infrastructure. But what differed was the amount in the levels of support in each community.

So in my research, I found that Ashwood Plantation, the all-White community, was sort of given the largest capital investment, but not only the capital investment. They were given more robust homes and schools and infrastructure.

And by more robust, I mean they were given a brick school rather than sort of a prefabricated, poorly designed school that was often given in Tiverton Farms or in Allendale Farms, for example. These all-Black communities.

Orangeburg was a little bit different again, as I mentioned, because it was interracial. It was one of the only communities that was explicitly fought against. There was an organized group of, I think it was roughly around 300 families in Orangeburg County, who actively resisted the construction of Orangeburg farms.

It was originally intended to be an all-Black resettlement colony, but because of resistance of local White elite families specifically, who didn’t want to have a Black belt in their town, the government essentially decided to reduce the number from 200 Black families to what was supposed to be 160 Black families and 40 White families.

And that number eventually came down to about 80 Black families and 40 White families. And so the dynamics were totally different in that community. They had to provide separate facilities.

And part of why I focus a lot of attention on this community in my chapter is because it sort of illuminates, in the highest definition, the fact that the New Deal government on the federal and state levels in this community were not willing to sort of push back or challenge any existing racial orders.

They were willing to provide funding to the extent that it would improve the individual citizen, but not improve the racial or social dynamics of the state. So this one— this community, Orangeburg Farms, was sort of in high definition demonstrative of these racial tensions at play within the community, but also in relation to the larger community, which they were sort of expected to participate in.

Sizek: Yeah, so what did some of those tensions look like on the ground at Orangeburg Farms? Like, on a day-to-day level, what were the interactions, or perhaps the lack of interactions, between the Black families and the White families that were there?

Yeah, it’s my understanding that the interactions on a sort of face-to-face daily level were not many, basically. This buffer zone was literally only feet apart. Like, the houses were not allowed to be in close proximity to each other.

So it was sort of a line dividing the White communities from the Black communities. And in some texts, I read that there was a fence. I’m not sure if they ever— there was a planned fence. I’m not sure if they ever actually constructed that fence in between the communities.

But because of segregation laws at the time, they weren’t allowed to be in the same school houses. So even the infrastructures that they had to produce required them to attend different schools.

And in some cases, before these schools were constructed within the communities, families had to go to community schools outside of sort of the community proper— the constructed community.

But sort of beyond just within the community, there were, I think, six or seven lynchings that happened within this time period between the ’20s and the ’40s within Orangeburg County. So they weren’t explicitly within this community, not that I can identify at least.

But there were still severe and intense racial tensions at play in the community. And so this was sort of an overarching or looming sort of background experience that informed the lives and the racial relations within this community.

Sizek: Yeah, and this also– for me, this raises a question of how you’re pulling together all of this information from different sources to try to figure out what’s happening here, because you mentioned there’s a planned fence that was going to be constructed. Maybe that’s coming from a federal document.

What was the work that you did to try to figure out what’s happening in Orangeburg Farms?

Vickers: Yeah. So this– a lot of my dissertation, but especially this chapter, is largely an archival project. Orangeburg Farms doesn’t exist anymore, and so it’s trying to sort of reconstruct or understand a community that you can’t go and visit, you can’t go and look at the homes.

It is a lot of looking at former photographs, or looking at photographs of former homes, and reading sort of through the lines of these archival materials. I had to go to state archives in South Carolina, University of South Carolina archives, National Archives in both DC and Atlanta to try and sort of paint a picture of this.

And I think to go back to the first question about sort of all of these different organizations being sort of formative in the creation of these resettlement colonies, it makes it really difficult to reproduce this story or to understand this story because you’re looking at FERA archives on one hand. And then you’re also looking at Civilian Conservation Corps archives, on the other hand, and Santee Cooper archives. So I’m sort of looking all over the place just to try and reconstruct this story.

And it feels like every different organization or former organization has their own take on how this community was supposed to look, how all of these communities were supposed to look. And it’s difficult to understand how they actually looked.

And so as I was constructing this story, some of the things I looked at included things like architectural renders of the prefabricated homes. I looked at lists and lists of seed grants that were given, livestock that were sort of housed within the community.

It’s a little bit ironic because it was easier for me to figure out how many cattle were in a given community or how many cattle that a specific family owned. But it was sort of impossible for me to figure out the name of every single family that lived within the community.

So a lot of this reconstruction work that I was doing in a historical sense was about pulling all of these puzzle pieces together, trying to figure out where the gaps were in telling this story through these extant materials about the geography, the sort of material — well, now the disappeared material reality that they lived within.

Sizek: So one of the people who you follow in this town of Orangeburg Farms is Cammie Fludd. And she sort of has an interesting and maybe different story from how you discovered some of these other people. So can you tell us a little bit about her and her role in the community?

Vickers: Yeah, Cammie Fludd was a home economics advisor. She had a few different positions. But as a home economics advisor, one of her tasks within the community was to offer guidance to women specifically about how to keep a home.

She taught them skills like weaving. She taught them how to bake, how to run a home garden in the backyard. But she was also sort of an interlocutor between farm agents at a state level and a county level and then also farmers on the ground.

So she was instructing them on how to sort of keep the best agricultural land, how to maintain livestock, things like that. She was one of dozens of home economics advisors across South Carolina — and probably 100 across the country — whose role it was explicitly to help create better people.

It was— her job was not explicitly about the farm itself, but how to sort of maintain an entire family, a farming family, a community oriented family, a civically-minded family within this sort of modernizing era.

So Cammie Fludd was from South Carolina. She worked specifically with Clemson University, part of their extension service. And she had a few different roles throughout her time working with Orangeburg Farms. And she also sort of worked with other resettlement communities from afar, including Tiverton Farms.

But because she was a local and because she was a Black woman, her role in Orangeburg Farms was specifically designed to sort of physically and socially get closer to the Black community. There were also White extension workers and White home economics advisors, and they largely worked sort of to the point of segregation at the time.

They largely worked with the White community. And in the times where they did work with the Black community, they were often met with distrust. They were often met with resistance, because a lot of these Black families specifically didn’t want an outside— an outsider, but an outside White person to come in and tell them how to live their lives.

And so Cammie Fludd was in this interesting position because she was an agent of the state, technically. She was an agent of the state. She was an agent of Clemson University. But she formed these really deep, intimate relationships with these community members in Orangeburg Farms.

And she was sort of growing alongside them. So part of the journey of her life, part of what I follow within this story, is not only her time within Orangeburg Farms, where she is helping to improve — and improvement is the word that they use — to improve the community as a whole in the Black community specifically.

But this is also a trajectory of her life. I follow her afterwards into Spartanburg, South Carolina, one of the largest towns— one of the largest cities in South Carolina — where eventually, there is a statue created in her honor. There are buildings named after her, public housing buildings named after her.

And she has this legacy of sort of trying to improve the Black communities around her and the communities within wherever she is living at the time. And so, part of this chapter is about studying improvement in how specific individuals are responsible for the improvement of entire communities, of entire races to some extent.

And improvement is a word that we hear a lot in relation to home economics and Blackness, essentially, in South Carolina, specifically in the New Deal, but sort of throughout the Progressive Era into the 1950s.

Sizek: So when you say improvement, obviously, there’s a sense of agricultural improvement, or maybe improving a field. How do they think about improvement, and what does it have to do with race in South Carolina?

Vickers: Yeah. So improvement was quite a racialized term. Improvement of the White community was often thought of in the context of creating better citizen consumers. That’s sort of the phrase that they used.

And actually, Mona Domosh, who is a professor at Dartmouth, wrote a really wonderful book called Disturbing Development, where she talks specifically about improvement in the Progressive Era. And so I think alongside that book as I think about the racialization of improvement.

So in the White context, its improvement in terms of becoming a better consumer, becoming a better citizen, becoming more active. And we see this in Ashwood Plantation, where a lot of the community events every single year, the May Day festival, performances that children put on, were all in service of demonstrating how they were becoming better every single year.

They were a strong community because of the government intervention. They were strong because they were independently minded, because they could produce on their own, because they paid their taxes every single year.

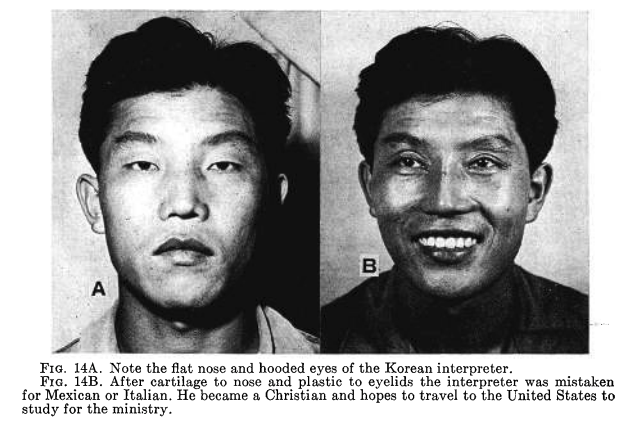

But then improvement in the Black context, in the other three resettlement communities — and I’m including Orangeburg Farms here because improvement is really targeted in Orangeburg Farms — so improvement in the context of Blackness was to bring them up to the standards of modern society.

So a lot of the improvement measures included things as simple as rural electrification. They believe that the Black populations before were not modern citizens because they were doing work by candlelight, for example, or they didn’t have modern fixtures.

Part of it also was intense health and sanitation measures in Black communities, whereas those were sort of marginal in White communities. And so they had extensive health testing, extensive health treatment.

There’s this belief that this population, the Black population, was pestilential or malarial. And so a lot of the targeted improvement measures were about cleaning up the Black population. But other measures included sort of trying to standardize how communities behaved in the home.

And a lot of the behavior— the behavioral improvements they were trying to make were to trying— were trying to make sure that the Black population was on par with or behaving in the same way that White families were in the home.

And so a lot of this, even when not explicitly stated that we are trying to bring you up to the standard of White people, it was based on White metrics of productivity, White metrics of health, White metrics of what is proper behavior in the school or in the home.

And this was met with some resistance in Black communities. But I think to bring it back to Cammie Fludd, for example, the government may be rightfully believed and understood that putting a Black extension worker into their homes and communities could offer a way for the government to physically get closer to these Black populations and improve them without the threat of sort of a looming government entity trying to enforce that.

Sizek: So you mentioned that the improvement projects were seen as improvements to the families, but they’re also improvements for the community and sort of new experiments in different forms of living.

And so you mentioned in this piece that Ellendale Farms was a place where New Deal economists thought that the settlers would have to create new institutions, and sort of create new ways of being. And all of them were also a little bit of a social experiment.

What were some of both the successes and the failures of these as experiments? You already mentioned that Orangeburg Farms no longer exists.

Vickers: Mm-hmm. Yeah, most of these communities no longer exist. In fact, I would say pretty much all of them no longer exist, at least in the form that they were in the 1930s and ’40s. Most of them failed by the end— by the end of the ’40s, but by 1950.

Except for Ashwood Plantation, in which the high school continued long after the community sort of existed in its structured form, existed with government funding. And a lot of this, I think, has to do with sort of the Whiteness of the community and the funding that was imbued into the community.

But I think, to your point about experimentation, I think there are a lot of experiments at play here, one of which I would say is health experimentation. I mention this in the context of Orangeburg Farms.

Essentially, the health programming that was happening in South Carolina at the time was one of the most robust health systems in place. This sort of pre-dated a nationally— a national health system, basically that we have a standardized health system across the state or across the nation.

And so this was sort of an experiment in community health, in public health on what at the time was a massive scale. There were also agricultural experiments, as you mentioned, and these were sort of scientific experiments.

I mentioned how Cammie Fludd acted as an interlocutor between the federal government and the local communities. But other extension workers, specifically ones that worked with the Clemson Extension Service, for example, where they had test farms on their campus — part of what they would do is go into communities, listen to the needs of the farmers or sort of identify issues that they were dealing with on the ground there, bring these questions and concerns to the scientists at Clemson University, who would run their own tests.

And so it was basically testing grounds in different agricultural spaces across the state. I mentioned that originally it was supposed to be a 1,000-unit single resettlement colony. And part of why they distributed it, beyond just community resistance at the time, was because they wanted to have communities situated in different agricultural zones, different agricultural regions across the state, in part because they could test out the success of cotton in one region, for example, or the success of growing corn in another.

And so these were agricultural experiments. I think to some extent— and what I argue in this chapter is about social experiments. Orangeburg Farms, again, is a good example of trying to see what it would be like to have an interracial community. To that extent, it was not successful because it was not actually an integrated community. It was a community that housed people of different races, but it didn’t really push back against any of the existing social orders at the time, which meant that it sort of was a failure in that it didn’t actually integrate anything.

And some of the other social experiments included things like requiring children to go to school up until or through high school, which was not standard at the time, especially for children of farmers, for example.

And to sort of bring it back to Ashwood Plantation, they do have such a robust alumni association from their high school, in part because the school lasted, I think, until the ’70s or maybe into the ’80s.

But because eventually, Ashwood Plantation, despite being the only White community, the White resettlement community at the time, integrated in the ’60s and ’70s. And so they expanded their reach with this single institution of this school that was sort of founded upon these federal dollars, this federal funding that these other communities weren’t given.

So it was an experiment in differential development, uneven development across the state. And that’s sort of– these series of experiments, I think, are sort of the sum of what the New Deal was. I think they were just throwing things at the wall and seeing what would stick.

And in the case of Ashwood Plantation, their school system is what really stuck. The buildings were torn down throughout the early- to mid-20th century, but the school was always this standing building. And in fact, the school itself doesn’t serve as a school anymore, but it still stands as like a gymnasium, an auditorium, a place where people gather.

So I think it’s sort of a testament to sort of the investment, like what sort of investments have longevity. In this case, a school does the lack of investment in these buildings that were to house people, was an experiment at the time, too, and obviously led to sort of the failure of the construction of these buildings, but the failure to continue to house them long-term.

Sizek: Yeah, so you mentioned a lot of sort of the infrastructure that sticks behind. What are some of the social things that you think maybe lasted beyond the duration after this program was over?

Vickers: Yeah, I think— at least in Ashwood Plantation, I think it was a lot of community networks. They had an annual May Day festival. And part of the May Day festival, it coincided with the National Health Day. And so one of the things they would do every single year is gather, throw essentially like a parade and celebration.

And this was a longstanding tradition thereafter. And so that’s sort of like a social gathering that I see as sort of developing the social network within the community, a space to convene, have these conversations, et cetera.

I think in terms of some of the other communities— so Tiverton Farms might be a good example where Tiverton Farms was founded at the same moment as a state park was founded right down the street. And part of the development of the state park required Civilian Conservation Corps labor.

At the time, originally, it was Black labor, and they met some resistance in terms of the White surrounding community didn’t want Black people to sort of exist within their community. So they had to move them essentially to another CCC project.

But one of the lasting social relationships that I follow within this chapter is about how a man who lives with— lives and lived within this community of Tiverton Farms started working at the state park at the moment he moved into Tiverton Farms.

So he was, I think, 14 years old and continued to work at this park six miles down the road for the rest of his life. And he built these strong relationships, not only within his immediate community, but within the park system.

He passed away in the 90s and is still honored to to this day as sort of an integral part of the formation of this park. But also because he had built roots in this community and Tiverton Farms only had 20-something houses by the end of the construction period.

It was all Black, only 20 something. In theory, 20 something families lived there but because he was born and raised there, refused to leave after sort of the failure of Tiverton Farms. And maybe refused to leave is too strong of a term because he had paid off his home in full.

He built— he essentially added additions to his home. He built bricks on the outside of his home to make it more durable and insulated in the winter time. And he also had children. And his children ended up moving into houses sort of adjacent to him down the street from him.

And so part of building a social network for him in this case was creating his own community, literally birthing sort of the new generation of this community. His children ended up marrying people who were also from that community. They still live in this community as recently as, I think, 2012.

I read newspaper articles about his daughter still fighting for their street to be paved in 2012, nearly a century after this community was created. And so I think that’s sort of a testament to sort of the woven social networks and the woven economic networks.

So much of his economic life and his ability to stay in this place was because he worked just down the street six miles, but he worked down the street from where he was living.

And then he was able to form these really strong connections because the community was so small, because it was only 20 families, and he knew every single person who lived on– they all lived on effectively a street.

And so despite the fact that they weren’t receiving the maybe financial and infrastructural investment that Ashwood Plantation was, they formed these really strong kinship networks that sort of essentially outlived the life of this community.

Sizek: Yeah. So you mentioned that often these social networks can survive, but ultimately, the communities sort of fall apart, either because the houses literally were not built to last that long. And one of the things that you sort of theorize this as being is “planned abandonment.”

So can you tell us a little bit about how you landed on this term as describing what happens to these communities?

Vickers: Yeah, yeah. So part of it– part of it emerged out of my identification or recognition that essentially, just like the prefabricated buildings were never meant to sort of last decades and decades, these communities were sort of never invested in in such a way that would enable them to endure, at least without sort of outside intervention as they were given at the beginning.

And part of me arriving at the term “planned abandonment” is because I was reading about planned obsolescence at the exact same time. And planned obsolescence is a concept that emerged in the early 1930s just as the New Deal was sort of ramping up. And the logic there was that, prior to the New Deal, a lot of goods, a lot of furniture and things like that, were constructed with longevity in mind. They were constructed to be purchased once and to last sort of a lifetime.

But the man who coined planned obsolescence argued that what we should really be doing to bolster the economy is to construct and to build and to sort of manufacture goods that did have an expiration date, in order for them to sort of consume more and put more money into circulation.

And so in thinking about that, and in thinking about these resettlement colonies, I was thinking about how specifically one of the concepts or one of the phrases used by the government was that these resettlers, these rehabilitants, as they called them, were designed to be tax payers and were designed to be people who eventually put more money into circulation for the government.

So they were given money at the outset and given loans that lasted five, seven, ten years that needed to be paid off. But at the same time, to the point about improvement, they were given tools and skills that would allow them to sort of do all of these things on their own.

Eventually, the idea was that they would never need federal intervention again. They would never need government dollars in order to pay their taxes and in order to pay for a loan and in order to purchase things on the market that would help them sort of feed the American economy.

So that’s why I think about it as planned abandonment. They planned only for the first five years, or they planned only for the first 10 years, which is why these a lot of these resettlement colonies had a lifespan of 1939 to 1949, for example. They only planned as far as sort of a 10 year span.

And then after that, they pulled out all of the funding, regardless of whether or not these families had paid off their loans. They had just never planned for a long-term lifespan. And I mean, one of the things I theorize as well is that they—

—part of this investment that was unevenly distributed, the uneven development of these communities, had to do with the fact that they were sort of put– literally putting money on the success of certain communities over others.

So the robust infrastructure put in place in Ashwood Plantation, for example, that I just mentioned as being sort of part of their longevity over time, had to do with the fact that the government was quite literally banking on them succeeding in paying off their loans, succeeding in continuing on after– succeeding in paying their taxes.

Versus Tiverton Farms, which I just mentioned, as recently as a decade ago still didn’t have paved roads. They weren’t banking on the success of that community. They were banking— because this was a Black community, they were banking on improving this population.

And to that extent, improvement perhaps was the end goal, but they weren’t there to sort of see it out beyond that time period. I think there were also a few other factors at play, right? In the early 1940s, the US entered World War II, and they sort of extracted funding from these communities.

They no longer needed to invest in them because they had other means of making money at that time. But there was— but part of my argument is that there was specifically this plan to only invest in the short-term in hopes that they would have long-term sort of profit from these people.

Sizek: Yeah. And so this also– I mean, for me and in thinking about the broader significance of this project is, like, what happens at the end of the New Deal and, like, how do you think about this fitting into the New Deal’s legacy and how we can think about this, this time that is now being brought back into the news through thinking about things like the Green New Deal, for example?

Vickers: Yeah. This is– it’s not the focus of this chapter per se. It’s something I am thinking about in my dissertation broadly in terms of sort of the second or the new life that the New Deal is getting in this present moment.

I think in terms of thinking about how it relates to the Green New Deal, for example, part of my critique of the New Deal right now is about offering avenues or pathways towards what I think could be more equitable policymaking within the Green New Deal.

So how do we attend to these historic wrongs or these historic unevenness– this historic unevenness that was sort of enacted within different communities with the same goal in mind, right? Like creating better citizens, despite not providing them with the same financial or social or agricultural opportunity.

Another factor, though, in terms of thinking about sort of the end of the New Deal, I alluded to it a little bit ago in terms of the start of the Second World War, but thinking about what came out, sort of what happened to American citizens on the other side.

If the goal in the New Deal, specifically New Deal resettlement projects, and more specifically in White resettlement projects, was to make them better citizen consumers, than we sort of see that at play in the 1950s with sort of this era of consumption, this era of modernization.

Like, this was a project to modernize America. But another component— especially in these rural resettlement communities, part of this modernization was rural electrification.

And rural electrification, not just for the sake of illuminating the nation, but also to make them more tied with urban society, and make them more tied with the rest of the nation. We do sort of see that emerge in the post— in the post-New Deal era.

And I should say that in terms of rural electrification, some of these Black communities specifically didn’t become electrified until the mid ’50s or the late ’50s, even into the ’60s. And so there was still this unevenness in the wake of what was supposed to be New Deal progress for all.

And so again– so to return back to the Green New Deal, for example. In thinking about how to make policy like that more equitable, I had a conversation about this with someone the other day about how it’s essentially not about sort of unilaterally implementing the same policies in every single community.

The New Deal itself was kind of a mess in terms that there were so many different organizations operating at local, state, national, federal levels. But part of that distribution of policy at multiple levels did function to enact these national policies differently within specific communities.

And although it wasn’t always successful, as I was talking about earlier, and although it wasn’t actually always equal, part of this had to do with who was in charge at these different levels, I think enacting policy with regional specificity— so the South is a very specific region in terms of its agriculture politics, et cetera.

With regional specificity and community specificity in mind is something that I’m sort of pushing for and pushing towards when sort of retrospectively looking at the New Deal itself.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

Sizek: Well, thank you so much for coming on the podcast and telling us a little bit more about the New Deal.

Vickers: Of course. Yeah, thank you for having me.

Woman’s Voice: Thank you for listening. To learn more about Social Science Matrix, please visit matrix.berkeley.edu.