If anyone at Berkeley is familiar the nexus of academia, policy, and advocacy, it is Robert Reich, the Chancellor’s Professor at the Goldman School of Public Policy.

Formerly the Secretary of Labor under President Clinton, Reich is one of the United State’s leading voices on the nation’s growing inequality. Recently, at the Aspen Ideas Festival (a co-production of the Aspen Institute and The Atlantic magazine), he had a chance to speak on the subject to some of the U.S.’s “top one-tenth of the one percent”, as he noted recently on his blog.

“When I suggested that we return to the 70 percent income-tax rate on top incomes that prevailed before 1981,” he wrote, “many looked as if I had punched them in the gut.”

Inequality is one of the world’s greatest and most complicated governance challenges. Social scientists who study the issue often reach dramatically different conclusions about its origins and policy implications. Indeed, many would still argue that inequality is inherent to capitalism; Thomas Pikkety’s re-treatment of Marx’s classic, for instance, has inspired a modern revisiting of the “contradictions of capitalism”.

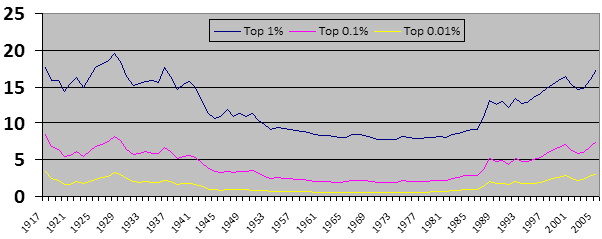

But that inequality is rising in the U.S. is clear, especially inequality in wages and particularly between wages at the top and everyone else’s. Among developed nations, and some developing nations, the U.S. leads the way. Today’s levels of income inequality have not been seen in this country since 1928.

The Aspen Ideas Festival has been held annually since 2005 and attracts some of the world’s preeminent businessmen, political leaders and policymakers, including both Clintons, Sandra Day O’Connor, and many more. This is an important audience for Reich’s message—both his analysis of inequality in the U.S. and its policy implications. Reich’s larger point is not simply that inequality is growing in the U.S., but that such growth is not actually good for the country’s capitalist economy.

“The question,” he began, “is when does inequality become so wide that it threatens a lot of things that we all hold in common: the economy, equal opportunity, and even the coherence of our society?”

As such, Reich’s approach to inequality is in fact quite measured. Far from being a communist, as Bill O’Reilly called him (O’Reilly claims it was a joke), Reich approaches inequality as an issue to be governed so that capitalism can work to the benefit of all and, ultimately, survive in the long-run.

On all three measures—economy, opportunity, and coherence—the U.S. is not doing well, according to Reich. While the size of the American economy has doubled since 1980, the median wage has remained roughly stagnant when adjusted for inflation.

Up until now, Americans have managed to use some coping mechanisms to keep up: women have joined the workforce in unprecedented numbers, both men and women are now working much longer hours, and many Americans, originally fueled by a belief in the ever-rising property value, have used their homes as collateral to borrow money.

When does inequality become so wide that it threatens a lot of things that we all hold in common: the economy, equal opportunity, and even the coherence of our society?

Today, though, these mechanisms are just about exhausted. And this is very dangerous for the broader American economy. While over two-thirds of our economy is based on consumption (of consumer goods, health care, education, infrastructure, etc.), consumption must inevitably decline in a society marked by stagnant wages and ever-growing inequality. Today, 65% of Americans live paycheck-to-paycheck. Indeed, Reich believes the last few years of relatively low post-recession growth are evidence of such decline.

Why can’t the poor move up the ladder into the middle and upper classes to generate the purchasing power that the American economy needs to sustain itself? After all, the U.S. is the land of opportunity. Reich believes that the political and economic drivers of inequality in this country also reduce social mobility. The U.S., for example, is one of only three countries recently surveyed by the OECD that spends more per pupil on middle-class and rich students than on poor students. Ultimately, almost half (42%) of children born into poverty will die in poverty—the highest percentage of any developed country. These inequities demand new policy approaches.

But the irony, Reich notes, is that inequality is so pervasive in the U.S. that its detrimental effects can even be seen in the polarization of American politics. As inequality has squeezed the middle class, reduced social mobility, and driven more Americans further into poverty, Reich believes people have grown angrier and even less open to the kinds of measured debates and policy approaches that the effective governance of inequality demands.

Surprisingly, though, Reich’s message is ultimately positive. He believes that inequality in America is actually a positive-sum game where both rich and poor stand to benefit from effective governance. The wealthy are better off, that is, with a small share of a rapidly growing economy than a larger share of a slowly growing or stagnant economy. As such, it is a vitally important issue for the country’s well-being and requires governance approaches that focus on these broader consequences, not only on the lower classes.

Reich likes to say that he’s not a class warrior, but a “class worrier”. And given the detrimental effects of equality on American economics and politics, all Americans—rich and poor—should share his concerns.