In 1875, a Liverpool doctor named Richard Caton found that when electrodes are placed on the surface of the skull, “the current is in constant fluctuation.” Such neural oscillations have continued to baffle researchers ever since. They appear at nearly every level of observation: single neurons firing in short bursts, local synchronized neural networks, and, of course, the large-scale “brain waves” that appear in electroencephalography (EEG) and define the stages of sleep.

No one fully understands where these neural rhythms come from and what they do. Recently, however, neural rhythms have shown up—almost synchronously—in published research from labs across UC Berkeley. Researchers are quietly beginning to uncover the role of neural rhythms in functions as diverse as navigation, executive control, motor learning, and working memory. Their discoveries have deep implications for neuroscience, and they may usher in a new wave of neurotechnologies.

Spatial navigation

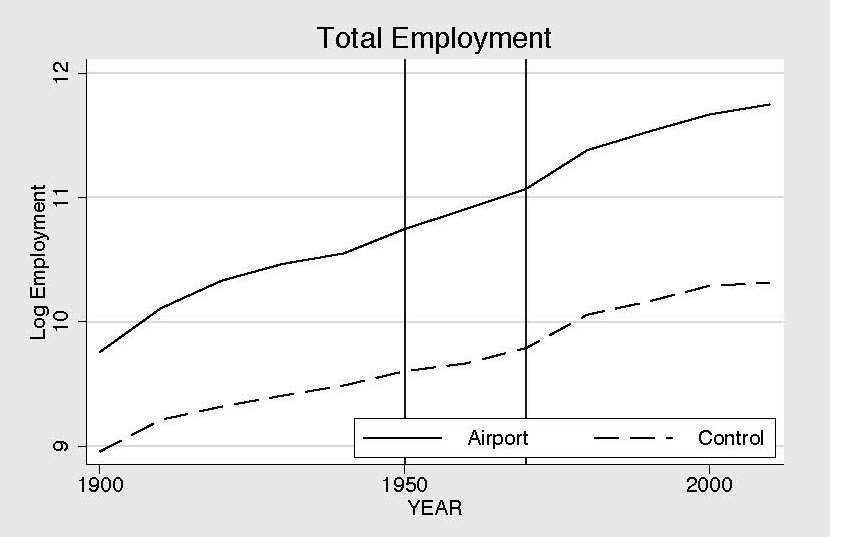

Neuroscientists have long observed that the hippocampus, an inner brain region responsible for memory and spatial navigation, undergoes mysterious electrical pulses about 6-10 times per second (6-10 Hz), a time signature known as “theta oscillation.” In May, a publication by UC Berkeley researchers in the journal Science may have shed some light on the information hidden in these hippocampal oscillations. A team led by Gautam Agarwal, a doctoral student in neuroscience, used implanted electrodes to measure the activity of groups of neurons dotting the hippocampus of rats navigating a maze. They showed that the electrical pulses traversing the hippocampus (visualized here) have a unique signature for each part of the maze the rodent passes through. They were even able to use the electrodes’ pattern of rhythmic activity to accurately predict rodents’ spatial position in the maze.

“By analogy to radio communication, we defined the theta oscillation to be a carrier wave whose modulation contains information,” the authors explain. In other words, they derived information from the hippocampal rhythm in much the same way that a radio receiver scans radio waves and converts them into music or speech.

More work needs to be done to understand why the hippocampal rhythm contains spatial information. However, many researchers have theorized that, like radios, brain regions communicate by oscillating in discrete frequency bands. In particular, some researchers have suggested that the hippocampus uses theta oscillation to coordinate spatial working memory with the prefrontal cortex, an area known for its role in in executive function, the ability to allocate attention, problem-solve, plan and execute actions.

Of course, this remains largely a conjecture, and what happens in the rodent brain may not be fully applicable to humans. The oscillations of the human hippocampus are not as strongly dominated by a theta rhythm. On the other hand, theta oscillations occur frequently in the human cortex (the outer brain structure that is more pronounced in humans than other animals). In addition, a recent Berkeley review concludes, based on several recent papers, that forming long-term memories requires the rhythms of the hippocampus to synchronize with those of certain parts of the cortex. If this synchrony occurs while subjects are memorizing words, they are more likely to remember them later on.

Neural communication

Recent studies in humans and primates have tested the basic notion that neural rhythms enable long-range communication between distant brain areas. For instance, a 2012 study led by postdoctoral neuroscience researcher Sepideh Sadaghiani at UC Berkeley, published in The Journal of Neuroscience, looked for rhythmic coordination across the entire human brain.

Sepideh’s team measured the brain activity of human subjects at rest with concurrent fMRI (functional magnetic resonance imaging) and EEG (electroencephalography). In fMRI, powerful magnetic fields are used to track oxygen in the brain, which is delivered to areas where the brain is active. fMRI yields a fairly slow signal, sampling every 2-6 seconds, but generates a fine-scaled image with a resolution of about 3 mm, measuring tens of thousands of sample points. EEG, by contrast, uses electrodes placed on the scalp to generate an extremely fast measure of brain activity, yielding multiple samples every millisecond. However, this measure has a limited spatial resolution. In this case, 62 recording channels were used.

Using both methods concurrently, the team found that a certain group of brain regions, known as the “fronto-parietal network,” has a unique rhythmic fingerprint. Regions in the fronto-parietal network, located using fMRI, are widely known to activate together when a subject is beginning a task or rapidly responding to something unexpected. Sepideh’s team found that when the fronto-parietal network is active, its constituent regions tend to oscillate together at frequencies around 8-12 Hz. In technical terms, they share the same “phase”—i.e. the peaks and troughs of their oscillations occur at the same time. This suggests that synchrony in the 8-12 Hz band might be the mechanism that allows regions in the fronto-parietal network to communicate when they need to rapidly integrate information.

A more recent study, published by UC Berkeley neuroscientists Antonio Lara and Jon Wallis in Nature Neuroscience , suggests that these neural oscillations have an important behavioral function. The two researchers used implanted electrodes to measure activity in the prefrontal cortex (PFC)—a little-understood brain region with a putative role in executive function—as subjects engaged in a working memory task.

The pre-frontal cortex might use neural rhythms to act like a quarterback.

Specifically, subjects had to remember whether the precise colors of squares that were flashed on the screen for half a second were the same as the colors of squares that reappeared a second later. They found that subjects were better at identifying the colors when the activity in certain prefrontal neurons oscillated strongly in the 1-12 Hz range. They concluded that these neural oscillations could allow the PFC to coordinate brain areas involved in memory and sensory processes, allowing perceptual information to be maintained in working memory. In other words, the PFC might use neural rhythms to act like a quarterback, directing players (allocating visual brain regions’ attention), monitoring their movements (keeping track of the color information held in memory), and attempting to deliver the pass (choose the correct button).

Scientists have also looked at how neural rhythms are synchronized during non-memory tasks, such as listening to music. A collaborative study by researchers at UC Berkeley and the Wadsworth Center in New York—published in the August 2014 issue of NeuroImage—measured neural rhythms with implanted electrodes while people listened to a song by Pink Floyd. They found that the music activated rhythmic connections throughout the auditory, frontal, and premotor cortices.

Another Berkeley collaboration—this one with the Leibniz Institute in Germany, published in February in the journal PLoS One—used implanted electrodes to peer at neural rhythms as people learned to perform various motor tasks. Each task required subjects to respond as quickly and accurately as possible to various cues using a keyboard. They found that as subjects got better at each task, the brain regions involved in the task oscillated in a sort of harmony: the phase of low frequency oscillations (4-8 Hz) was highly correlated with the amplitude of high frequency oscillations (80-180 Hz). They interpret this as indicating that, for improvement at the task to occur, long-distance communication between brain regions (reflected in low frequency oscillations) had to coordinate local activity within each region (reflected in high frequency oscillations). In other words, each region started acting like a worker on an assembly line, timing its own activities to be in lockstep with the other regions involved in the task.

New technologies

A common thread throughout these studies is that neural rhythms seem to allow brain regions to communicate, whether the goal is to navigate the environment, remember visual cues, interpret auditory signals, or plan motor movements. But what happens if these oscillations are manipulated directly? This is already being done by neuroengineers, who are finding that neural rhythms can be harnessed to operate brain-machine interfaces (BMI), and can be stimulated to treat disorders and enhance cognition.

A study published by UC Berkeley researchers in the April 2014 issue of The Journal of Neural Engineering showed that neural rhythms can be used to operate a 2D cursor. As the researchers used electrodes to record activity from the motor cortex, subjects had to use their brains alone to move a digital cursor toward targets presented on a monitor. The direction and speed of the cursor’s movement were controlled by how the rhythms recorded from each electrode were oscillating in a chosen frequency band. Using each of three different frequency bands (0-40 Hz, 40-80 Hz, or 80-150 Hz), subjects were consistently able to learn to control the cursor. Previous BMI devices had only used the amplitude, rather than the rhythm, of brain activity. This new approach could open up exciting new channels for brain-machine control.

Other groups have manipulated neural rhythms directly using a noninvasive technique called transcranial alternating current stimulation (tACS). In tACS, a weak, alternating electric current is induced between two electrodes placed on the surface of the scalp. A German study published in the February 2014 issue of Current Biology showed that tACS could be used to strengthen or bolster brain waves at selected frequencies, simply by alternating an electric current at the corresponding rate.

Recent studies have already used this technique to generate some stunning effects on behavior and cognition. A 2013 Oxford study in Current Biology used tACS to “phase-cancel” resting activity in motor cortex—i.e., align the peaks in electrical stimulation with troughs in resting activity, and vice versa. As an example, this is the same technique that is used by noise-canceling headphones to eliminate ambient sound (as explained in this video). They used this to reduce motor cortex rhythms associated with tremors in Parkinson’s disease, resulting in an almost 50% reduction in tremors. (A study with rodents suggests that a similar technique could reduce epileptic seizures by up to 60%.)

Another remarkable 2013 study in Current Biology used tACS for high-level cognitive enhancement. By applying tACS over people’s frontal lobes, researchers enhanced their fluid intelligence: they made people 15% faster at solving difficult logic problems.

An Emerging Field

Although these advances are clearly impressive, the science of neural rhythms is still in its adolescence. So far, engineers trying to leverage this science have had to play a bit of a guessing game: along with the site and amplitude of recording or stimulation, they’ve had to speculate on what phase and frequency to use. With all of these parameters at play, it’s nearly impossible to find the perfect combination.

However, as the science of neural rhythms progresses —driven by research at UC Berkeley and elsewhere — we’re likely to see this technology improve. Expect to hear more about brain rhythms in the coming years.