War is back. Open military operations in Europe and the Middle East have driven an escalation of geopolitical tensions in those regions. The conduct of warfare is changing, too, fueled by the deployment and sometimes live-testing of new technologies. Meanwhile, a new cold war seems to be settling in. The growth of China’s economic power and worldwide influence has triggered proliferating sovereignty disputes and defensive trade and security policies.

In this Matrix on Point panel, UC Berkeley experts discussed these and other transformations, and offered their views on what to expect in the short to medium term.

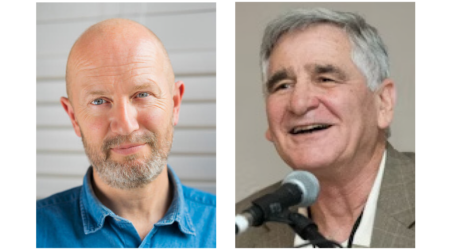

Recorded on September 30, 2024, the panel featured Michaela Mattes, Associate Professor in the Charles and Louise Travers Department of Political Science at UC Berkeley; Andrew W. Reddie, Associate Research Professor at UC Berkeley’s Goldman School of Public Policy, and Founder of the Berkeley Risk and Security Lab; and Daniel Sargent, Associate Professor of History and Public Policy at UC Berkeley, and Co-Director for the Institute of International Studies.

Co-sponsored by the Berkeley Institute of International Studies, the panel was moderated by Vinod Aggarwal, Distinguished Professor and Alann P. Bedford Endowed Chair in Asian Studies, in the Charles and Louise Travers Department of Political Science; Affiliated Professor at the Haas School of Business; Director of the Berkeley Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation Study Center (BASC); and Fellow in the Public Law and Policy Center at Berkeley Law School, all at UC Berkeley.

Matrix on Point is a discussion series promoting focused, cross-disciplinary conversations on today’s most pressing issues. Offering opportunities for scholarly exchange and interaction, each Matrix On Point features the perspectives of leading scholars and specialists from different disciplines, followed by an open conversation. These thought-provoking events are free and open to the public. Learn more at https://matrix.berkeley.edu.

Podcast Transcript

[MUSIC PLAYING]

[WOMAN’S VOICE] The Matrix Podcast is a production of Social Science Matrix, an interdisciplinary research center at the University of California, Berkeley.

[MARION FOURCADE] Hello, everybody. Welcome. Thank you for coming to our first Matrix On Point of the ’24 ’25 academic year. My name is Marion Fourcade. You know me. I’m the director of Social Science Matrix here. So when we planned this panel with Julia Sizek, I should give her kudos because she really helped organize this back in the spring, we decided to call it War is Back.

And of course, it’s always a challenge to plan an event months ahead because you don’t know how things will evolve. But sadly, the panel and its title are more appropriate than ever. Ongoing military operations in Ukraine and the Middle East have expanded further. New technologies continue to be deployed to deadly and sometimes unprecedented uses, for instance, very recently in Lebanon.

And meanwhile, a new Cold War seems to be settling in. The growth of China’s economic power and worldwide influence has triggered proliferating sovereignty disputes and defensive trade and security policies. So to help us grapple with these issues, we have assembled a fantastic panel of Berkeley faculty. Note that today’s event is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Institute of International Studies.

Now, before I turn it over to the panelists, let me just give you a preview of what we have in stock for you the next few weeks. Tomorrow, we have a presentation by Bradley Onishi on Project 25 and Christian Nationalism. On October 9, our next Author Meets Critics will feature Paul Pierson and Eric Schickler for their most recent book, Partisan Nation.

And then the next two Matrix On Point will be about the election, Voices From The Heartland with our own Arlie Hochschild next October 21, and then shifting alignment in later that same week actually. But right now, our topic is war. So let me introduce our moderator, Vinny Aggarwal.

Vinny Aggarwal is distinguished professor and holds the Allan P. Bedford endowed chair in Asian studies in the Travers Department of Political Science. He’s also an affiliated professor at the Haas School of Business, the director of the Berkeley Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation Study Center, and a fellow in the Public Law and Policy Center at Berkeley Law School. His authored books include, among many titles, Liberal Protectionism, International Debt Threat, and Debt Games.

And he has not one but two forthcoming books, Great Power Competition and Middle Power Strategies and the Oxford Handbook on Geoeconomics and Economic Statecraft. His current research examines comparative regionalism in Europe, North America, and Asia, industrial policy and the political economy of high technology economic statecraft. So without further ado, let me now turn it over to Vinny. Thank you.

[VINOD AGGARWAL] Should I come up there.

[MARION FOURCADE] Don’t have to.

[VINOD AGGARWAL] OK, well, I have a mic, so I will just sit down and introduce my colleagues here. So it’s a great pleasure for me to moderate this panel. I think you were optimistic. You said the panel might be obsolete. Unfortunately, I don’t think this panel will ever be obsolete. I think war will be with us for a long time. So even if there’s not war involving the United States, there’s clearly wars going on around the world. And there has been since eternity. I think so, unfortunately, or fortunately for those of us who study war, there’s lots of room to do research.

So without further ado, I’m just going to introduce Michaela Mattes, who’s an associate professor in the Political Science Department. Michaela’s research looks at cooperation and conflict issues, alliance formation, and things like that. Andrew Reddie, who’s at the Goldman School of Public Policy, with whom I work a lot on high technology conflict, looking at quantum computing, AI, synthetic biology, and cybersecurity. And he will be talking about the technological aspects of international conflict.

And Daniel Sargent, my co-conspirator in the academic freedoms seminar series that we run, who is a professor, both in history and public policy. I think beyond that, you can go look at their bios online. So I’m not going to waste too much time. And I’m just going to start in order. Michaela, why don’t you take the floor and you can begin?

[MICHAELA MATTES] OK, so I wanted to start a little bit by interrogating the title of this event. That war’s back, which assumes that war was gone at some point. And certainly, my colleagues who study Civil War would heavily disagree with that. I mean, civil wars have been active and alive and well, you could say, in the 21st century. Thinking of Syria, Yemen, Ethiopia, North Sudan, and then also Myanmar, Burma.

I think when the claim about more being gone maybe is a little bit more applicable to interstate war. And so that’s where my commentary is actually going to focus on, so wars between recognized state members of the international system. And here, of course, there was a time about 15 years ago or so, like in the 2010s, where scholars and observers were very optimistic that war is in decline. So very famously, there was Steven Pinker’s Better Angels of our Nature argument that war is in decline.

In general, we’ve seen this decrease in violence over centuries. We’ve moved away from things like chattel slavery and human sacrifice, some of the more extreme types of torture. And so war will also decline as a result of our ability of humans to use our reason or reasoning skills, in order to create mechanisms to constrain war. And there will, of course, also other scholars such as Joshua Goldstein and John Mueller, who formulated similar arguments. They pointed more to maybe peacekeeping and the strengthening of norms around the constraining the use of force as mechanism for why war should have declined and will continue to decline.

And to be fair, they had a point because after 2003, there was no inter-state war until 2022 when Armenia and Azerbaijan fought each other. And then, of course, the Ukraine war in 2020. Sorry, 2020, Armenia, Azerbaijan, 2022 in Ukraine. And also, there was a very long period of great power peace, really, since World War II, which is arguably the longest period of in centuries. So there was a lot of optimism there.

That being said, some of us were always a little skeptical. I remember being asked in 2010s at my former workplace by a colleague, why do you even still study inter-state conflict? It’s not a topic anymore. And I didn’t quite agree with it, and nor did others. And so some people took this up much more systematically, and I think provided some good evidentiary basis that there really is not a decline in war, even inter-state war.

So I think important there is Bear Braumoeller’s work on Only The Dead, where he shows using data on violent conflict between states, not just wars, but generally, also lower level sorts of violent conflict between states. That there may have been a bit of a decline since 1990, but that there have been other ebbs and flows in history, right? So that war has gone up and down in history over centuries. And so that there is nothing particular or special in this decline that we saw then, and that there’s no reason to believe that it won’t go up again.

He also did some interesting analysis looking at the correlation between various factors that we to be associated with the likelihood of war or violent conflict between states such as alliances, arms, races, territorial disputes, democracy, trade. And so what he found is that the pattern of association between these factors and conflict has not changed over time. So it’s not that the factors that increase the likelihood of conflict have now a weaker association. The ones that increase the likelihood of peace have a stronger association. We’re not seeing that.

Another I think really interesting argument also that questions this decline in war came from Tanisha Fazal, who suggested that scholars often use this operational criterion of 1,000 battle fatalities to define what war is. And so this is problematic because our battlefield medicine has gotten so much better than it was in the past. And so now soldiers can be rescued from the battlefield when they’re injured within this golden hour, right?

The first hour after injury, which really increases their prospects of survival. There are antibiotics, antiseptics, all kinds of other innovations. So that even if fighting actually has the same intensity as it had 100, 200 years ago, we will see fewer soldiers die in these conflicts. In fact, over long periods of time, the ratio of casualty to killed was 3 to 1.

And for the United States, in Iraq, Afghanistan, it was more like 10 to 1. So what this means is that it may look like there is a decline in inter-state war, but that’s an artifact of this criterion that we often use to identify what inter-state wars are, which is these 1,000 battle fatalities. And really, the intensity of conflict is no less than it has been in the past.

Now, I feel like, given what’s happened recently, I think people are more skeptical about this argument in general. There are also other points that one could make, not just addressing that the decline in wars, maybe not quite what others have suggested, but there are other factors that suggest that it’s not clear that war is in decline or has ever been in decline or will go into decline. I mean, for one, the International system remains anarchical, meaning that there is no enforcer that can enforce any kind of peaceful deals between states or that can punish an aggressor.

Furthermore, states remain heavily armed. In fact, when we look at data of the Stockholm International. Peace Research Institute, or SIPRI, and their latest data is for 2023, we’ve seen yet another increase in worldwide defense spending. It’s actually the ninth consecutive year of increase. It’s the biggest jump, in fact, since 2009. And 2023 had the highest military defense expenditures in the world of any year that is recorded by SIPRI, and that even adjusts for inflation, right? So we have anarchy. We have states armed to the teeth.

And we still have plenty of pairs of states or as we call them, dyads, that have significant disagreements between them. I’m sure we all can come up with them, right? They’re the perennials of North and South Korea, India and Pakistan, China and India, Iran and Israel. And then there are some new conflicts to pay attention to such as Somalia and Ethiopia, and Ethiopia and Egypt as well. So there is clearly conflicts between states still.

Furthermore, there is reason to expect that maybe conflict is intensifying. I mean, the great power rivalries were already mentioned, right? So the US and China in particular, that rivalry has intensified using all kinds of economic tools of warfare that Vinny could certainly talk to. I would say that the US, Russia is probably weaker now given that Russia has been so weakened in the Ukraine war. So that’s a very good investment of the US to weaken Russia as a rival by helping Ukraine fight Russia. So that’s maybe less of a threat at this point than China is.

Furthermore, we aside from this great power rivalry, also have other new issues that come up to the table. So in particular, climate change is going to bring up some new potential conflicts. A very, I think high profile one is the Arctic. Once the ice melts in the Arctic, that means there’s going to be major competition over what our significant gas and oil reserves there, and also really important trade routes. So we’re already seeing countries positioning themselves in the Arctic and starting to compete over there, including non-arctic nations like China is.

And then, of course, when areas become uninhabitable, we will see population movements and refugees and migration that can create further tension, that can lead both to civil conflicts and to inter-state conflicts as well. I think another argument to make that conflict is not in decline, we shouldn’t really expect it to be in decline, especially in the future, is that some of the factors that those optimists pointed to that were constraining warfare between states are not things that are permanent. These are things that can change and actually sort of fade away over time.

So some of the arguments were, for instance, about the role of trade in containing conflict, right? Once countries trade heavily, then there is an opportunity cost to conflict, which makes it even less desirable. Well, we have seen in part, as a result of the pandemic, but also in part of a result of great power competition that some of this trade has plateaued and even declined in parts, although there’s a little bit, I think, an increase very recently.

But again, there is no guarantee that this very high trade ties will continue into the future that could constrain conflict. Furthermore, I’m sure most of you or all of you have heard of the Democratic Peace idea, that democracies are less likely to fight each other. And so, yes, after 1990, right, we saw an emergence of more democracies, but that’s been in decline, too. So if we look at Freedom House, the 2024 report, they find that there has been the 18th consecutive year of decline in global freedom scores. So democracy is also weakening.

A third pillar, arguably, of peace in post World War II period and after 1990, was the United States as the hegemon. That would ensure peaceful relations, especially in its areas of zones of influence in Europe and Latin America and some of Asia, and this Pax Americana as a feature that ensured a more peaceful world. Well, I mean, US dominance has declined relative to its closest competitors.

But maybe even more importantly, there is also a lot of hesitation domestically within the US of allowing the United States to be a policeman of the world in the future. So I actually looked it up and it turns out that fewer and fewer Americans are willing to support the US playing a leading or major role in World politics. The last I saw was still 2/3 of Americans. So I think it’s not completely gone at that point. But to the extent that those trends become stronger and the US becomes less willing to become involved in conflicts, that is an important factor.

Another pillar of peace arguably was the strength of norms, such as the norm of territorial integrity. Well, that took a really big hit, of course, with Russia’s attack on Ukraine. And so whether that norm remains intact or maybe even strengthened is very much a function of what will happen with Ukraine in the long run.

So if Russia is allowed to win and take parts of Ukraine, then that will have really Weakened the norm of territorial integrity, and other countries with similar territorial aspirations might just think, OK, we can tolerate some international opprobrium and sanctions in the short run. We just have to wait it out and then we will be able to get that piece of territory, right? So in a way, war holds the key to war here, to future wars is one way to think about it.

Finally, just two concluding comments, both building on Bear Braumoeller’s work that I think are important to highlight. One is that fundamentally, war has a big random component, right? So as scholars, we can identify the correlates that increase the risk of war or decrease the risk of war. But whether war occurs, there’s randomness to this. Whether a particular event is the event that suddenly people think is worth fighting over is something that we cannot easily predict.

So it’s very possible that we see actually no wars happening, even though the risk of war is just as high as it has been in the past. And so that’s something important to keep in mind, that even if we haven’t seen war, it doesn’t mean that the risk of war isn’t high, and that there isn’t this potential for some event that we cannot foresee entirely to really spiral out of control and not just lead to war, but also lead to major war.

And so a second related consideration is that I think it’s dangerous to be too complacent about war. So I think we all sleep better if we think that there’s not going to be much war. But at the same time, I think it is important to remember that it is a possibility in many parts of the world and that the step from war to escalating in a large war may not be a huge step. And so by not being complacent, right, we can more quickly act if disputes seem to be spiraling out of control.

And so just as a mini example of that, I mean, thinking back to the beginning of the Ukraine war when President Biden alerted the various allies that Russia is planning aggression, they didn’t believe it. So I’m European, and German in particular, in the first initial originally. And in Germany, decision makers did not believe that Russia was going to attack Ukraine. I mean, to Germans, it seemed like Russia had integrated into the economic order. It was benefiting from things. It was a partner.

And so there was a lot of reluctance and hesitation to recognize this, and therefore also, delayed action. So maybe if people had not been too complacent about it and had taken stronger measures to really signal to Russia this was unacceptable, maybe deterrence could have worked in this particular setting. And so that’s just important. I think, as we move forward, maybe and I feel like I sound very pessimistic here, though I hear my co-panelists have similar pessimism, so I don’t want to panic everyone, but I think it is there’s some value to being watchful of what is going on.

[VINOD AGGARWAL] Thank you, Michaela. I’ll remember that next time we’ll have you go last, not first, so that everyone won’t be depressed. But brilliant. I think a brilliant discussion of all of the key factors that suggest that war is still with us, unfortunately. So Andrew, are you going to say some really warm, positive, fuzzy things?

[ANDREW REDDIE] Oh, absolutely. Yes indeed, about the AI among other things. No, thanks, Vinny, for corralling us. Many thanks, Marion, for having me. It’s a privilege to be back at the Social Science Matrix. I received support from Matrix as a graduate student. So graduate students, there is a future, I promise. It’s a privilege to be here. So you’ve already heard from Michaela the premise war is back. Maybe troubling, but there’s also a debate that we’re having about whether and how technology is reshaping warfare as well. So that’s where I’m going to end up focusing my remarks.

And I’ll start with a rhetorical question. So what do senators, military leaders, and authors of science fiction have in common? And the answer is more than perhaps you might think. So they have visions of the future of warfare involving technologies, fundamentally different from the present, from super soldiers with biological or robotic enhancements. Have you seen this in The New York Times. It’s there if you look for it, to drone swarms using biometric data. I submit to you the future of life video called slaughterbots. To maneuverable missiles that travel to the target over 6000km/h. Those are hypersonic capabilities.

And I’m more than happy to talk about each of these during the Q&A. That said, my concerns, as you’ll see, are perhaps a little bit more prosaic than some of those headline grabbing technologies. And I’ll do my best to name check each of the ones that you might expect me to talk about. So nuclear capabilities, AI, military integration, advances in ISR, intelligence surveillance reconnaissance capabilities. But before we begin, any given any time that I’m asked to give a talk on emerging technologies, I also want to talk to you about the boring stuff, because the boring stuff is also not going terribly well.

So first, there’s various non emerging technologies, and perhaps mundane concerns that deserve the attention of all of us in the scholarly community and also our policymakers. We have a major challenge inside the defense industrial base. We no longer produce enough bullets and shells to take up what we’re sending overseas to the likes of Ukraine and Israel. We are not currently able to produce a plutonium pit for our nuclear weapons, and that’s despite our nuclear posture review calling for an increase in the number of plutonium pits to be created in order to keep the nuclear deterrent exactly where it lies today.

Moreover, no technology or widget exists in a vacuum. So any time that you see individuals, whether it be scholars or policymakers, talking about hypersonic weapons, for example, the end widget, it’s the very end of the product cycle. We have all sorts of the supply chain risks to worry about as well. So in another life, the National Labs before it came back to the Academy, that was what we were really focused on.

There are a variety of different individual technologies that all go inside any particular capability, each of which are vulnerable to cyber attack. The example that we were talking about up here before. You also have the headlines about the pagers in Lebanon. That’s exactly the kind of thing we’re worried about in the context of our nuclear weapons. For example, our cyber satellites used for reconnaissance capabilities. And so there’s all sorts of things to worry about at this technology meets war intersection.

Second, what constitutes emerging technology as it pertains to warfare is at best, a fuzzy concept. Indeed, in my class on war question mark emerging tech, we spend a lot of time problematizing the concept itself. And ultimately, we have lots of technologies that we overestimate in terms of their proximity. So for example, you’re seeing probably a lot of headlines about Terminator and Skynet and artificial general intelligence.

On the flip side, we also have technologies that always appear 10 years away and then all of a sudden they arrive. How many of you use ChatGPT? And nobody saw that coming. And then all of a sudden, all of our students are writing their essays using it, and we all have to adjust. The invention of a given technology is also the only first step to being fielded by a military.

One need only look at the early years of aviation for lots of examples of problematized use cases. So we were dropping bombs out of hot air balloons and we’re using flammable airships to drop ordnance. Not a good combination. And so it takes time to figure out what strategies and doctrines, and also institutional characteristics go into actually deploying a particular technology in war.

And Michaela gave you lots of readings. So I’ll just point to Mike Horowitz, recently out of DOD and back to Penn, where he runs the Perry World House. He talks a lot about the degree to which the governments and militaries need the institutional capacity to actually come up with the appropriate combinations of technology and how they might be used on the battlefield.

And then finally, we should be skeptical of claims that any particular technology is a game changer. Indeed, that’s one of the things that really annoys me as an academic in this space. What I’m interested in is how each characteristic of a weapon system, whether it be its range, its precision, its blast effects, its radiation effects, how do those characteristics actually end up altering what a country is likely to be able to do with it vis a vis an adversary, by the way.

One of the major challenges we have analytically in this space is it’s not just the creation of a technology in a vacuum. It’s the United States developing a capability, the Chinese developing a capability, the Russians, the Europeans, et cetera. And the ways in which countries around the world think about these technologies looks very, very different. If I were to say AI to all of you, you immediately think of LLMs. In Russia. If I say, they think about robotics and robotic applications.

So if any of you have seen the Boston Dynamics, little robot, it looks like a little dog, that’s what they’re thinking of when we say AI, that’s different for us. So ultimately, we have to be really careful when we talk about what’s actually changing inside of this space.

And I spend a lot of my time thinking about first strike stability concerns and the degree to which deterrence might hold or not hold in a new technological environment, the degree to which technology impacts crisis stability, so how likely I am to escalate a conflict or not. And then also arms race, behavior. And I think Mikayla did a nice job of showing you that that arms racing is actually happening as we speak. So when I’m studying an emerging tech, I want to see how things are actually changing as these various different countries move against one another.

With that said, you probably expected me to talk about the sexy stuff. So here we go. All right, so in the nuclear state of play, are things changing? The answer there is it depends. So to a large extent, we have the Chinese developing new capabilities, both quantitatively and qualitatively. So all of a sudden, US Defense planners have to think about what happens when China has 1,000 nuclear warheads rather than their current 300 to 500.

And also, what happens when they start to have ICBM silos, and a submarine launch deterrent rather than their land-based mobile missiles? And so that impacts all sorts of things. For example, the amount of time that it might take for them to fuel rockets and launch them, which obviously gives us time to respond, and also change the types of risks we might be worried about the Chinese actually bringing upon themselves. So I’ll point to you the fact that it took us more or less two decades to build the nuclear triad that we live with today, right? So the combination of submarine launch forces, ICBMs, and bombers.

And subsequently, we made all sorts of institutional decisions that tried to address this, what we call an always never dilemma. I always want my nuclear weapon to work when I ask it to. I never want it to go off unless I ask it to. Eric Schlosser’s Command and Control does a really good job of pointing out to where that always never dilemma has failed. But if you’ve got a country like China who’s rapidly creating new legs to its triad, all of a sudden you drive up the potential for accidents. And that’s something that we worry about quite a lot.

Also too, I’ll point out that one of the things that senators want to do as soon as they hear that China are increasing the number of nuclear weapons, is that they want the number of nuclear weapons in our arsenal that matches what the Chinese have and the Russians have together, OK? Is that a good idea? Is that not a good idea. For what it’s worth, I’m a fan of offsetting capabilities, not matching capabilities. There’s a tendency in our Congress, bless them, to see an adversary deploying a capability and then saying we need that too.

And so that’s actually traveled to, for example, the Russian development of, and let’s get this right, in orbit nuclear tipped anti-satellite weapon. You saw this in March Time. So the Russians have developed a new capability that would effectively make entire swathes of orbit uninhabitable for our satellite systems, which is a good thing to do if you’re Russia because we rely on our space assets for pretty much darn near everything in terms of our military command and control assets.

And so immediately in response, we had various members of Congress saying we should have that too. Well, the Russians don’t rely on space for command and control nearly as much as we do. So what we should be really thinking about is offsetting capabilities. And so all sorts of different questions about what the Chinese are up to. The Russians, Putin’s never seen a nuclear weapon he doesn’t like. So they’re deploying nuclear torpedoes, you might have heard.

And there’s also renewed conversations about dead hand nuclear systems. So there, you have some of the autonomy concerns matched with nuclear capabilities. So don’t move to Seattle, and perhaps thinking about don’t live don’t live in San Francisco. He also wants to develop and is tested a nuclear powered nuclear tipped missile, which is a terrible idea. You don’t want that to go boom. And indeed, he ended up irradiating part of Finland during one of the tests. So at the same time as you have the Chinese doing their quantitative increase and qualitative breadth, you’ve also got Russia qualitatively moving things as well.

At the same time, you’ve got the End of Arms control as we know it. So various different agreements have collapsed from the INF Treaty to new start more recently. And so there’s real questions about whether we might end up finding ourselves on a period in which we really do increase the number of nuclear weapons again moving forward. And this, of course, happens in the United States at the same time as we’re undergoing our own modernization effort.

And I should be very clear, the program of record does not say that the United States is increasing or broadening capability. It’s the Obama administration’s modernization plan that effectively tries to take type for type the triad. So we’re moving from the Minuteman III, ICBM, to GBSD Sentinel, ICBM. We’re moving from the Ohio class to the Columbia class of submarines. And we’re moving away from the B-2 to the B-21 bomber force. And we’re just doing it on a one for one basis.

But of course, we have conversations about how much that is costing, whether we need ICBMs moving forward, where it is what we might actually spend money, increasing capability. And of course, on the back end, you worry that the incremental increase in nuclear numbers might subsequently increase the likelihood of use. And one of the major debates is taking part in the field, and that I do some of the wargaming that my team does around is really on this low yield nuclear weapons question.

So the idea being that you might want to have low yield nuclear weapons in the US arsenal to match what the Russians have by way of non strategic nuclear weapons. But of course, how do we think about low yield nuclear weapons? Does that make them more usable? Is it more palatable if I’m causing small amounts of damage rather than large amounts of damage? And so that conversation is getting played out right now in terms of the submarine launched cruise missile with the nuclear tip, and specifically whether to deploy that on attack submarines or not.

Of course, the response to that potential development has been met with some of our colleagues, like Vipin Narang at MIT with derision, because obviously, the problem is that if I have a submarine surfacing, launching a cruise missile, and we have nuclear tipped capabilities in the arsenal, now our adversaries no longer know whether they have a nuke coming at them or a conventional asset coming at them. And of course, if it were me, I would assume the worst. And our fear is that our adversaries would too. And so you get escalation spirals from there.

OK, so that was the nuclear weapons. I mean, I guess I brought it up very briefly when I was talking about the plutonium pits. But things are also not going very well in the mundane side of the nuclear enterprise. So the recent congressional Strategic Posture commission report suggests that less than half of our facilities are fit for purpose in terms of the facilities at Lawrence Livermore, National Lab, Los Alamos, Oak Ridge National Laboratory. And so there are real pressures here in terms of us being able to actually feel the deterrent that we’ve come to rely on, let alone think about increases.

When it comes to the AI, hot take time. I’m a bit skeptical about whether AI changes a great deal. We’ve had AI capabilities inside of the military for a long time, nigh on six decades. And traditionally, we’ve used it for things like early warning systems, so signal detection algorithms, anomaly detection algorithms to figure out when adversaries are launching something hot at speed coming from a particular place, and/or to figure out whether they’re doing something unusual.

That said, even in the run up to the Russia, Ukraine crisis that Michaela mentioned, it was actually the blood movement, not the military exercises that was the smoking gun in the data that led to ODNI saying the Russians are going in. So we’ve had these capabilities for a long time. And ultimately, they’ve proved fairly effective.

We also use a lot of the tools that were developed in the Valley to manage supply chains in the military space, too. So predictive maintenance, predictive logistics, right? Moving my maintainers and materiality around the world, such that I have a probabilistic rate of failure in my F-35s, for example. It’s higher than the military would want. And so we use algorithms that help move things around. So in the same way that Tim Cook justifies being CEO of Apple, our military planners, right, also are moving things around the chessboard based on various different algorithms.

But what all of these applications have in common is that the failure modes are fairly mundane. So ultimately, if my engineers and my material are missing one another in Okinawa by three days, I’ll get yelled at, but nobody’s going to die, OK? So one of the applications that does start to worry people is on the decision support side. So the use of various different AI tools to actually help militaries around the world make decisions about what it is they ought to be developing, when they be they ought to be deploying capability, and when they should go, go, go.

And again, there’s a really good video by the Future of Life Institute called TLDR that you can go and watch, that really makes that risk salient. One of my bugbears with that particular video that really pushes on automation bias concerns where members of the military getting an algorithm saying, “You must escalate, you must escalate,” and the human operator is effectively saying, “Yes, yes, yes, yes, yes,” because they’re getting service by the model so quickly. So that’s an automation bias problem.

The issue is what’s the data that actually goes into these algos? So we’re all care carrying, right, academics in this field. And we know data sets like correlates of war, Vinny may have coded it once upon a time. Are we comfortable using correlates of war or MIDS and other data set in the field to make decisions about war and peace? Or even some of the work that I do. Are we comfortable with my synthetic data generating war games to be used to make decisions about war and peace.

I see people saying, no, not really, right? And so can we imagine a world where militaries were overestimate the capability of what you’re able to get here. So there’s massive training data concerns. So altogether, given the failure modes and the potential deleterious consequences of deploying the assets, there’s a lot to be reticent about in terms of how AI is going to be changing warfare, at least any time soon.

Where things actually are moving the needle is actually, again, somewhere where we don’t spend enough attention. But intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance capabilities. Here at Berkeley, we’re developing all sorts of new, different types of sensing, whether it’s synthetic aperture radar, or hyper and multispectral imagery tools, new IR imagery tools. And all of those are getting deployed on increasingly interesting delivery platforms.

From micro satellite systems to pseudo satellite systems, such that we have a pretty good sense of everything that’s actually happening on the Earth’s crust, more or less in real time if you really want to spend the resources to get it. And that has use cases in all sorts of different places from finance, but also in war. And so that really has moved the needle. Indeed, in my view, the Chinese have actually changed their nuclear posture because of these capabilities, and because they feel that we know where their land based mobile missiles are, rightly or wrongly, given these areas, different types of assets.

So will these technologies ultimately change the game? When I say drone to my students, they often think of things like the MQ 9 Reaper, right? Massive systems, 60-foot wingspan, top speed of 300 miles an hour, right? Really sexy system, OK? But the ways that drones are actually being used in the battlefield today are DJI quadcopters coming out of China. That people are throwing over the horizon and looking at the trench next to them.

Indeed, the war in Ukraine has a lot in common with World War I, right? At the same time, as I talked to you about AI, new types of nuclear systems, et cetera. And so that’s something that we really need to square. So right, ultimately, be wary of the science fiction of it all, and really think hard about how things are shifting. So we’re really looking for the discussion to follow, happy to pull on any of these particular technological threads. Looking forward to this session. Cheers.

[VINOD AGGARWAL] Thank you, Andrew. I’m going to ask you later whether AI will kill us all. That’s a different issue.

A different question.

Use against the Russians or the Chinese. OK, next, we have Daniel. Thank you, Daniel. Sargent.

[DANIEL SARGENT] All right, Andrew has talked about the future, so I’m going to talk about the past. And I’m going to lead off with a set piece juxtaposition of classical political theorists. And the problem that I want to use these theorists to interrogate is the political nature of man. To speak to this transcendent question, I’m going to summons two venerable authorities, Thomas Hobbes and Jean-Jacques Rousseau. These canonical theorists of politics, as most of you know, proceed from opposing premises.

For Hobbes, of course, the political nature of man is malignant to the marrow. Avarice, fear, and strife are for Thomas Hobbes, are primordial political condition. It is, of course, to emancipate ourselves from the primordial violence of this pre political condition, Hobbes argued, that we build political institutions. We created a political hierarchy, Hobbes speculated, in order to escape from the primordial violence that Hobbes calls the war with a double R E, of all against all.

This entirely speculative anthropology is, of course, the point of departure for a great deal of modern theorizing about international relations. The familiar premise that world politics are defined by the condition of anarchy, by the dearth of superior authority, that is endures in the writings of canonical theorists from Machiavelli to Morgenthau and beyond.

Inter-state war in the Hobbesian paradigm is both rooted in our fundamental political natures as human beings, and a consequence of institutions that have evolved over time to constrain substate violence, but have failed in the containment of violence at the inter-state level. Wherein, the war of all against all endures, much as Michaela observed in her opening remarks.

Let’s turn from Hobbes to my counterpoint, Rousseau. Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s founding premise is, of course, the reverse of Hobbes’s. For Rousseau, the political nature of man is inherently benign. For Rousseau, what creates conflict and strife is the historical advent of political complexity. The invention of private property, Rousseau argued, thrust men and women into a new era of exploitation and history, into a new era of violence and war. War, in short, is for Rousseau, a result of political institutions, flawed institutions, not of inherent human nature.

Now, back in the early modern period, the conflict between these opposing views of man’s political nature was, in essence, a normative dialogue, a normative conversation for the simple reason that theorists lacked hard evidence upon which to predicate their conclusions. The political nature of pre-political man varieties in the 17th and 18th century was inherently unknowable. Today, we are happily able to bring a little bit more evidence to bear on the question.

Archeological, surviving, anthropological, and even zoological reasoning deployed by way of analogy, points to an overwhelming conclusion. Hobbes was right. War is hardwired into human nature. This, I believe, is a crucial premise from which to interrogate the proposition that war is today back. If war is inherent to human nature, if it’s part of who we are as human beings, we’re going to have to proceed in recognition of the reality that war never went away. The propensity to initiate and to escalate war is part of who we are as humans.

And yet, the historical record nonetheless records a measurable reduction in the incidence of war over the very long term. Conclusions derived from the skeletal remains of hunting gathering peoples indicate, in the pre-political condition, a propensity to violent death far beyond what even the most violent modern societies record. Put simply, we are far less likely to perish at the hands of our fellow human beings today than was the case for our pre-political forebears, say, 10,000 years ago.

How should we explain the macro historical reduction in the incidence of violent death, in the incidence of war? Two hypotheses seem to me plausible. One is moral evolution. I should be clear. Here, I am not talking about changes in our biological natures. Such evolution occurs only at timescales far vaster than the horizons of human history. Rather, I am talking about the possibility of evolution in our normative or cultural precepts.

The second possible explanation for the long term decline of organized violence involves institutions. Perhaps we might contemplate. We have succeeded in building institutions capable of restraining, at least to a degree, are immense and amply demonstrated propensity to violence. In the minutes that remain, I would like to contemplate the utility of each of these explanatory hypotheses with regard to the problem of war in the contemporary era, and I’m going to focus first upon the institutional hypotheses.

Utopians in the modern era have recurrently conceived institutional solutions as a necessary, inevitable response to the problem of war. The examples range from Immanuel Kant’s Federation of Republics, a possibility, of course, discussed in Kant’s famous essay on perpetual peace, to Woodrow Wilson’s League of Nations.

What such frameworks have sought to accomplish in the end is the submission, at least to degrees, of the decision making sovereignty of states to some kind of superior political authority. World government at some level has always situated at the heart of institutionalist solutions to the problem of war. Such solutions, I would argue, have for the most part, achieved little of any real consequence in the modern era, except perhaps at the regional scale.

European integration is probably the outstanding example of a Kantian or institutionalist solution to the problem of war. Elsewhere, whatever institutional solutions human beings have devised to the problem of war have been far more provisional, far more ad hoc in nature than those that Immanuel Kant and Woodrow Wilson envisioned.

The interlude of great power, peace that occurred during the second half of the 20th century, I would argue, owed far less to the institutional accomplishments of the United Nations than it owed to the accidental geopolitical equipoise, the nuclear standoff that we call the Cold War. Put bluntly, the immense power of nuclear deterrence functioned for a time as a meaningful disincentive to the initiation and escalation of great power war.

What this means, I think, is that we have achieved no meaningful institutional solution to the problem of war. Rather, the operative question for today is whether the ad hoc solutions that were improvised in the aftermath of the Cold War– sorry, in the aftermath of the Second World War, in the era of the Cold War, that is, retain the power that they manifested in the classical Cold War era. I would argue that they do not.

Nuclear deterrence has shown itself to be incapable of restraining conventional aggression, as we see in the case of Ukraine. Similarly, alliance relationships have also demonstrated themselves incapable of constraining military escalation by subordinate allies, as we see in the Biden administration’s demonstrated incapacity to constrain the war that Israel is today waging against Hezbollah in Lebanon. In short, the limited ad hoc solutions to the problem of war that emerged during the second half of the 20th century are today demonstrating themselves to be wholly unequal to the awesome and eternal task of war prevention.

Let’s turn then to the problem of culture. To what degree has cultural or moral evolution meaningfully constrained our propensity to wage war? The first point that I want to make is that we should not underestimate the power of culture to exercise a pacifying influence on the affairs of states. This is the point at which I may part company with my colleagues in political science. I would argue that during the medieval era, Europe lacked meaningful institutional solutions to the problem of war.

But the ideological power of the universal church nonetheless functioned as a potent cultural discouragement to the initiation and escalation of inter-state violence. My colleague in the history department, Jeff Koziol, has actually written recently about this medieval experience in his excellent book, The Peace of God. Conversely, I would argue that the erosion in the 19th and 20th centuries of the pacifying force of Christian ideology in Europe led to the rise of secular ideologies unconstrained by the kinds of normative commitment that Christianity had once affirmed.

The result was, of course, the 20th century, probably the most violent century in the long and torrid history of complex human civilization. Here, we might also reflect on the secular ideology of human rights, an ideology that in our times has sought to present itself as a universal and general solution to the problem of war.

Does the ideology of human rights not affirm, after all, the unique and singular value of all human life? Does it not affirm the universality of rights, perhaps including the right to be free from premature and violent death? Unfortunately, the secular ideology of human rights are modernity’s alternative to the secular constraints that Christendom once imposed upon European states, has demonstrated itself in the absence of effective enforcement mechanisms to be, essentially, incapable of constraining war, as the torrid history of substate war in the second half of the 20th century amply showcases.

To the extent that culture has exercised any meaningful, constraining effect on our propensity to engage in violent conflict, I would argue that the operative cultural constraints in our times have originated, not in metahistorical commitments, whether secular or Christian, but rather, in the lived experience of the recent past, in recent historical memory. that is.

On this concluding point, I’m going to offer you just one piece of suggestive evidence. In the summer of 1972, the Soviet Communist Party General Secretary, Leonid Brezhnev, hosted Richard Nixon for a summer meeting. It was held just outside of Moscow in a luxurious dacha. During the course of this conversation, Brezhnev at one point turned to Nixon and declared, of course, a war between us would be wholly unthinkable. We can all agree on that. Both men, it hardly needs to be said, were veterans of the Second World War. Brezhnev, of the Eastern Front, Nixon of the Pacific Theater.

Today, their generation has passed from the scene, and we as a result, no longer possess the tangible human connection to the horrors of past wars that their lived experience provided. The kind of historical reconstruction that writers like me produce, I would suggest, is a poor substitute for that lived experience.

As a result, I would conjecture, the cultural constraints on the initiation and escalation of warfare that we initiated from the Second World War are today fraying. In the absence of effective institutional constraints, constraints that we have failed to devise over the past 70 or 80 years, we must see the inevitable progression of cultural and historical memory as a source for grave concern.

Our problem, I will conclude, is not that war is back, at least not yet. Rather, our problem is that our experience of war has faded, especially in the West, and it is perhaps in the depleted soil of our cultural memory. A cultural memory from which war is all too absent that the seeds of new cataclysms may be germinating. That’s my optimistic conclusion.

[VINOD AGGARWAL] Well, it’s been a real fun day so far, so maybe I should just stayed home. Yes, so I think I’m not going to ask questions. I’m going to actually open it up to the audience. And if the audience doesn’t have any questions, I have about 25 questions to ask you, but I will refrain from doing that. So why don’t I just ask for questions? Just introduce yourself if you can. And please try to ask questions, not make statements if you can. Yes, sir. Just introduce yourself.

[AUDIENCE MEMBER] Yeah, I wasn’t– hoping I wouldn’t be first. Hi, I’m Damian Shanks Dumont. I’m a PhD candidate and Berkeley Law’s jurisprudence in social policy program, where I study international legal history. With respect to, it seemed all of you were struggling with this idea that war is back, and the idea that it was ever gone in the first place. And it strikes me as– and I promise this is in a statement, we’ll get to a question, but it’s background. With respect to Professor Mattes’s point that there’s the threshold that’s written into the formalistic criterion in the Geneva Conventions of 1,000 deaths.

But there’s a secondary criteria on as between the first and the second additional protocols between international armed conflict and non-international armed conflict. And it seems non-international conflict, or what we would colloquially call Civil War, has been a constant presence this entire time. And that still, that rhetoric of non-international conflict still plays a big role in the wars that we’re seeing today.

Putin discussed the invasion of Ukraine as a police action, and today, the denial of Palestinian sovereignty is a big part of the retributivist flavor of the actions with respect to Gaza and now the extenuation of the war against Hezbollah, and the Houthi rebels, these use of indiscriminate weapons that would be blatantly a violation of international humanitarian law, and yet are done and justified through this idea of the criminal law corollary of what Bush’s war on terror was, right? Non-state enemy combatants.

So I would like, I guess, the ruminations of all of you on what role, retribution, and the way that the wars are being played out now in the popular consciousness, in the rhetoric of state officials, and in the media as not actually interstate war, but some third thing that has the flavor of criminal law and yet has these effects of being international war.

[AGGARWAL] Start with you?

[MICHAELA MATTES] I was hoping to get some more time to think about it. I mean, there was a lot in your question, so I’m– can you just state it really succinctly?

[AUDIENCE MEMBERS] How important is it that today, most of the wars, that the wars that we’re seeing are not justified and spoken about as if they’re interstate wars, i.e., World War II, but rather as police actions or war against terrorists, or the inherent right of self-defense as against non-state actors?

[MICHAELA MATTES] I guess one, it’s not directly in answer to your question, but a thing to think about. So there’s some interesting work in international politics about why it is that we have seen a decline in formal declarations of war. It used to be the case that countries would formally declare war, and they don’t anymore. And so there’s some debate about why that is. And some would say that it is actually to try to circumvent some of the constraints of international law that have become much stronger, of course, in the aftermath of World War II. And so we’re not seeing that as much anymore.

Other arguments are more that you don’t want to be seen as an aggressor, right? So I think that, so in part, that maybe would be one way to think about it. The reason there are these statements that what Russia is doing is a police action, or that emphasizes the not inter-state nature, is a way to try to minimize the appearance of international aggression, which I think there are strong norms against that at this point in the world. And the more countries do that, the weaker though, those norms are going to be.

[VINNIE AGGARWAL] Andrew, do you want to add something?

[ANDREW REDDIE] Yeah no, I mean, I think Michaela is spot on. And also too, obviously, there’s a reputation benefit from using that type of language, but there’s also a material benefit. So if you’re Russia, you get to– I’ll turn this back on again. You get to escape the sanctions regime, because you’re able to convince some number of countries that the US action is inappropriate, given the language that you’re using.

To give you a tech flavor on the question, militaries have long been entirely agnostic as to whether it’s a Civil War or a state-based war in terms of the lessons that they’re learning. So the historical example, often, is the Spanish Civil War that effectively created the conditions for blitzkrieg from the Germans. So the Germans were effectively learning from the Spanish Civil War and then subsequently using that. And again, we have all of this conversation today about, well, what is it that the Chinese are learning vis a vis a Taiwan Straits contingency from the war in Ukraine?

And are we learning, potentially, the– ignoring the lessons from the Ukraine in terms of how we should be retooling the US military, given that we tend to like large programs that are incredibly expensive, where the cost of force exchange ratios are never going to be in our favor. And should we be moving more toward attritable systems, for example? And so we’re having that debate as well. And so for the military planning perspective, war is war. I don’t care what you call it. I’m going to learn my lessons from it either way.

[AGGARWAL] Daniel.

[DANIEL SARGENT] I’ll be succinct. Look, I don’t know that the phenomenon you describe is especially novel. The US wages wars in the 19th century against the Spanish empire, against Mexico on the pretext that these states are unable to constrain transnational acts of aggression against the United States. So I think what you’re describing is an old theme.

I don’t see, I’m afraid, international law as a institution that has demonstrated a particularly robust capacity to protect the inhabitants of weak and failing states against acts of warfare by better organized neighbors. I think the only meaningful defense that we have seen to such acts of warfare is the organization of a more effective state.

[VINOD AGGARWAL] OK, Jack. I know who you are, Jack. Just introduce yourself.

[JACK CITRIN] Yeah, I want to say that these were fabulous presentations. Really brilliant. Since I retired a few years ago, I’ve avoided as much as possible political science discussions, but I’m really happy I came to this. I just want to ask one very question. The underlying premise may be unspoken, is that war is a bad thing. Avoiding war is really [INAUDIBLE]. Maybe war is the right thing for a particular state to do at a particular time.

And sure, there can be costs, but if you take the example of Polk initiating a phony war with Mexico, certainly, if you think about the long run benefit, to the US is quite clear, maybe not morally, but in terms of all kinds of material. And I think that’s often the case. And so sometimes, you take in the case of Israel, preemption has often been their strategy, given that they’re surrounded by people who don’t accept their existence. So maybe in terms of war is back, it’s one-sided. The question never went away. I think you’ve convinced us all.

No.

But the particular instances can sometimes, I would think from the perspective of the actor, be rational choice. Just a simple, rational choice. This is to our benefit, and to hell with the UN and to hell with everyone.

[MICHAELA MATTES] No. That one, I’m happy to go first on. When I teach my students in conflict management class, I often struggle with this because they think all conflict is bad. And my reaction is like, no. I mean, sometimes it’s conflict or a really terrible piece. And so that it’s not necessarily a bad thing, I think, is it rational from an individual state actors? Well, our series would suggest it does not. But I think the question more is that normatively always bad or good?

And I don’t think it is normatively always bad to go to war. I mean, I am happy as a German that the US decided to go to war with Germany in World War II. I mean, that was the right thing to do. It was the better thing to do. So certainly, think an interesting extension here is pressing for a ceasefire. That may actually be a bad idea, sometimes to press for a ceasefire fire.

We know from research in international relations, both civil wars and inter-state conflict, if the parties are pushed to a ceasefire too quickly before beliefs have converged about who will likely win at what cost, those types of peace deals do not last very long. So, yes, you’re saving people in the moment, but you’re actually risking a recurrence of conflict later and you may be overall worse off than that. So I totally agree that war is not normatively undesirable under all circumstances.

[VINOD AGGARWAL] Good. Andrew.

[ANDREW REDDIE] Yeah, I mean, one of the things that Fearon’s bargaining model really struggles with the productive aspects of war as well. So I’m going to take this in a tech direction. No surprise there. I mean, despite the fact that the Valley likes to ignore it, a lot of the inventions that came out of the surrounding 100 miles or so were funded ultimately by DOD. So with thanks to the US military for GPS, the internet, semiconductors, or even prior to that, right? Research that happened in military contexts leading to nuclear energy and nuclear medicine, et cetera. And so there is a productive side of it. Now, right, do you necessarily want that, right? Probably not. But you do get all of these externalities out of it as well.

[VINOD AGGARWAL] Daniel.

[DANIEL SARGENT] Sure. Look, I agree with the premise of the question, and I actually agree with the historical case that you invoke. But I think risk assessment always involves two dimensions. One is probabilistic, the other involves the impact that the eventuality would produce. And I do think when you think about those two dimensions of risk impact, you have to think about great power war or systemic war in the nuclear age as an eventuality that would be unambiguous and unacceptably atrocious.

And that’s a reality that I think does bear powerfully on any conversation about war in the contemporary era, and especially on any efforts to assess the risks and prospects of war in relation to historical experience. So I would very much align with historians and political scientists who take seriously the transformative impact of the nuclear revolution for our discussion about war. And I think it has to be reflected upon in the relation to the question that you posed, Jack.

[VINOD AGGARWAL] Thank you, Daniel. So next question. Yes, in the back. Could you introduce yourself? Oh, you have the mic. Did you have a question?

I do.

OK, we’ll ask you and then we’ll go back.

[AUDIENCE MEMBER] And thank you for your presentation. I have actually three sets of questions. My name is Julian, I’m a visiting scholar in sociology. Sorry, my three sets of questions. The first is about the role of church in designing mechanisms of governance, then the distribution of the experience of war, and then the space for moral in today’s war. And I’ll try to connect them together. So you say that during the middle age, church was some sort of coping mechanism for waging war.

I would say also that historians are sure that the peace of God were also the war against the others. It was very common for church leaders to go to war. It was very common to go to war for the formation of knights and the whole hierarchy. So I’m wondering, which type of regulating mechanisms do you really see at work during that time that would inform today’s war?

Second, you mentioned that there was the first said experience of war was fading right now in the West. I’m quite surprised to hear that because I see also the amount of veterans in the United States. And I’m wondering as well, what the other scholars here make of the fact that perhaps there is a professionalization of war in the West, but the firsthand experience of war and conflicts around the world is certainly rising through refugees, migrations, and conflicts.

So what to make of the distributary between the professional of wars in the West and a civil society is increasingly enrolled into violent conflicts. And third, about moral. That may be more to Andrew, but is there a space for moral discussions in AI wars? And what is it today? Thanks.

[VINOD AGGARWAL] OK, lots of questions. Short answers, please. Start with you, Daniel.

[DANIEL SARGENT] Great. Look, I don’t want to take too long on the question. It’s difficult to make statistically well-founded comparisons between medieval and modern international politics. And I’m not presuming to deny that crusades occurred or that they were violent. But when you look at the scale of medieval European warfare and compare it to the scale of modern warfare, or for that matter of pre medieval Roman era warfare, you’re looking at a more marginal phenomenon in the life of the society. And I think that does reflect, to a degree, the power of cultural or normative constraints upon state behavior.

Your second question about– it’s a good question, and I actually hope that more robust representation of veterans in our Congress can exercise a pacifying effect on our statecraft as a society. But if you compare veteran representation among members of Congress, it’s a very easy metric to deploy. The evidence is unambiguous. Our lived experience of total warfare as a society is today minuscule by comparison with what it was for the post World War II generation.

[VINOD AGGARWAL] OK Michaela, do you want to add anything?

[MICHAELA MATTES] I guess just a couple of thoughts on the war fatigue argument. I mean, my first reaction, and this is not a really good one to Daniel was like, well, I mean, in World War II, they should have learned from World War I and they didn’t, right? But I mean, of course, I don’t believe the one case ever shows something to be incorrect. I think there is– I do agree, though, with the argument that, yes, there are many, of course, soldiers in the US who served in Afghanistan and Iraq, but they’re professional military, and they’re professional soldiers.

And so most people, I don’t think, engage with them very much, right? So it’s not a shared experience among us in the same way that World War II would have been or World War I would have been. And in terms of the experience of individuals in war, there’s some interesting work in international relations where actually, politicians who served in the military but did not fight tend to be more war prone or conflict prone, more willing to use force, than even ones that never served.

And the ones who are the most– sorry, the most warped– sorry, the most conflict prones are the ones who served but didn’t fight, and the ones who served but did fight tend to be actually quite avoidant of conflict. So that it’s a little bit of a mixed pattern.

[ANDREW REDDIE] Yeah, really good question. I mean, as you can imagine, there is a massive moral discussion around AI and military integration here on campus. Stuart Russell in engineering school, is a major driver behind the campaign to stop killer robots, which you might have heard of. He’s also fairly high up in the Future of Life Institute that I name checked a couple of times that are producing various different videos to try to drive some public sentiment around these moral concerns.

Toby Ord and Ewen MacAskill, the longtermism movement, you might have heard of. So for them, AI, climate, and nuclear are the three things that we need to be focused on when you’re thinking about risk over the centuries type term. And then more prosaically, right, we have inside of the UN, a group of government experts focused on lethal autonomous weapons issues. Although there, I’ll point to the clashing of realpolitik on the one hand and normative concerns on the other.

And so lots of discussion inside of that framework about the degree to which lethal autonomous weapons are distinct from chemical weapons, or landmines, or cluster munitions. And there’s something of an argument that ultimately, we get agreements like those because they’re no longer militarily useful. And indeed, where they are military useful, like here in the US, we don’t sign the agreements. And so given the lack of certainty around where and under what conditions these capabilities will actually be useful, it strikes me as very unlikely we’re likely to see anything fairly strong coming out of that loss process.

And what we usually tend to find is that the Russians and the Chinese will back one particular international governance conversation, and the Americans and the Europeans will back another one. So, for example, in the cyber domain, we’ve got the GGEs, the group of government experts that are now led by Russia, China. And we the OEWG, the open ended working group, and they actually can’t even come up with a list of common definitions around cyberspace. And so we’ve got the same problem happening in lethal autonomous weapons. That said, I still got to go to Geneva and have the conversation, so that’s fun. But yeah, it’s alive.

[VINOD AGGARWAL] Good. We had somebody in the back. Do you have a mic there?

Yeah.

That’s great. Can you just introduce yourself?

[AUDIENCE MEMBER] Hi, I’m Cat Smith. I’m a fourth year undergraduate studying political science and legal studies. And my question is more specifically for Professor Reddie, but the rest of you are more than welcome to answer. Also, thank you for being here. It’s been an awesome panel to listen to. You talked a lot about the great powers of Russia and China specifically, and the development of nuclear programs. Is there a US agenda for the proliferation of programs for more minor powers such as North Korea, India, Pakistan, and Iran are also programs that are talked about as potentially developing? And how is that being addressed? And then curious if surveillance might be the answer for that, because as you said, China is changing its posture. So how could that work potentially for minor powers?

[ANDREW REDDIE] Yeah, good questions all. So with regards to North Korea, ultimately, that’s what our missile defense capability is supposed to be addressing. Missile defense, by the way, being an autonomous weapon that’s already deployed and would not work if you put a human on the loop. So that’s what that’s for. Obviously, we fear about Iranian proliferation. And also, too, you would fear other countries in the region also responding. So, for example, it’s very unlikely that if Iran were to get the bomb, that Saudi Arabia wouldn’t follow immediately.

Just one note there. When Iran produces its first weapon, it will not announce it. Like the North Koreans before them, you’ll want to have an arsenal that you think is large enough to give you some semblance of survivability. So you’re not likely to know that Iran has a weapon until they have on the order of 30, 50, et cetera, and have figured out how to deploy them, so some sort of delivery system.

India, Pakistan, super interesting. Traditionally, Pakistan was our ally. The war on terror got a little bit icky. Now, we look to India and try to use India as a counterbalance to China. And so we brought them into an arrangement called the quad. The problem with the Indians, of course, is that they still actually buy military equipment from who? Moscow, and have long ties to Russia. And so we have the enemy of my enemy is my friend dynamic, but everybody’s not on the same side.

And so that’s one of the major bugbears that I have with Cold War 2.0, as the way of describing this reality. In some ways, our reality is far more complicated. So I’m just back from Omaha and STRATCOM, and they talk about the 2 plus peer problem. It’s the fact that you’ve got to get this, right, videos where it talks about spaghetti or noodle bowls. It’s noodle bowls of alliance frameworks, and it’s terribly complicated.

On our side, for what it’s worth, the South Koreans are fairly nuclear latent. They can probably produce a capability pretty fast. The Japanese, the same, the Germans the same. And it was obviously here in this building where Walt said, “Give nuclear weapons to everybody, the world would be safer.” I’m not so sure he’s right. But I think that whether we still have the same number of proliferated states in 2030 as we do in 2024, I don’t feel terribly good about it. Not to be even more pessimistic than we’ve been the rest of the time.

[VINOD AGGARWAL] Michaela, do you want to add anything?

[MICHAELA MATTES] I wanted to add something pessimistic. Same here. I mean, looking at Iran, right? Just took a big hit to its axis of evil with the decimation of Hezbollah and Hamas. So what are they going to do, right? I mean, it seems to me like shifting more towards nuclear is one way of trying to bolster up. So whatever that will lead to, we don’t know. But just making things a little bit more pessimistic.

[VINOD AGGARWAL] I think we have enough pessimism. Does anybody have anything optimistic? All right, let’s take more questions. Oh yeah, Rosy.

Hi.

Introduce yourself.

[AUDIENCE MEMBER] A professor of political science at Temple University, and visiting scholar at the Berkeley Economy and Society Initiative. This is a really fascinating conversation. Just a couple, I guess a question based on a few things have been said. So [INAUDIBLE] mentioned rationality around war. And then Julian mentioned the crusades, right? And I’m just thinking about, Daniel Sargent, what you mentioned about the universal ideological power of the church. How about just war? And the idea of there may be some morality to go to war to defend certain ideas and powers, interests, and so forth. So I thought if you have some thoughts about that, and welcome the other panelists too. Thanks.

[DANIEL SARGENT] Absolutely. No, I think that’s a great question. And of course, just war theory, beginning really with Augustine, is the foundational step on the genealogical progression that takes us to the modern Geneva and Hague Conventions, to the institutionalization of rules of war. What we should make of such rules, I think in the end, that’s a normative question.

I think that the effort to institutionalize rules of war entails a recognition of the legitimacy of the premise of Jack’s question, that war can sometimes be just a necessary. It probably also concedes the permanence of war. It may have what we consider to be a normative benefit insofar as it meaningfully constrains the brutality with which war is waged.

[VINOD AGGARWAL] Anybody else want to add or should we continue?

Hey.

Yes, sir.

Hi, so I’m TK.

Please introduce yourself.

[AUDIENCE MEMBER] Hi, I’m TK. I’m a graduate of history PEIS here from Berkeley. I work in the higher education field. I won’t go specifically into it. So we know in the 1960s and ’70s, there were major militant movements on student campuses. They took direct action, violent and non-violent, like People’s Park, right? Black Panther Party. And if you look at the US diplomatic cables around the world at that time, they’re saying like, “Hey, this is making us look bad, right? The intensity of the fighting internally, right? We better loosen up, right? We better scale down, right?

There were talks like this, both the way they treated people here and abroad. But during the Iraq war protests, they said, these were the largest anti-war protests in history and was just ignored, right? It was just ignored because they were very calm, orderly. So I’m just wondering if you think that the lack of– the more pacifist approach to, or the lack of more direct action contributes to the kind of wars we are engaged in right now, and what seems to me to be a disregard for protest movements in general.

[VINOD AGGARWAL] OK, who wants to start?

[ANDREW REDDIE] I’ll give a crack at it. I mean, ultimately, the salience of national security issues and the body politic, particularly in the US, is relatively low, and always has been. I mean, you can see that in the polling around the election, for example. National security ranks well behind everyone else. Everything else you could possibly be worried about from the economy, which is usually number one, to abortion issues, et cetera. And so the degree to which you’re going to agitate for any particular national security concern is going to be low, all else equal anyway, despite the fact that, of course, that’s the only place where the executive actually has privileged access to policymaking. Terribly ironic. They don’t control the Fed. So I would note that.

I mean, a recent event that sounds similar was Project Maven. So we had in the Project Maven episode in 2017, a group of Google engineers that said we’re not going to complete a DOD contract, which was focused on bringing autonomy into DOD operations, entirely not kinetic, right? So not war facing capabilities. And that was something of a black eye for the government. And they had to think really seriously about who to use in the future because, of course, DOD bringing in Google was their attempt to bring in the next generation of company that wasn’t Lockheed, Raytheon, Honeywell, et cetera. And that was something of a black eye.

Now, of course, after Russia, Ukraine, a lot of the tech companies are now very much in line with the US government. And so Microsoft, for example, provide much of the cyber backbone to Ukraine. And you also have various luminaries in business like Eric Schmidt actually writing the drone policy in terms of thinking who they should be procuring from for Ukraine as well. And so that relationship is very different in 2017 to 2024. So it can turn quite quickly.

[DANIEL SARGENT] Yeah, can I just push back a little bit of the premise. For all of the scale and volume of the anti-war movement, Nixon wins the ’68 election and then escalates the war. And then in ’72, he trounces McGovern, who runs as a peace candidate. So I’m not sure that protest does have such a powerful, constraining effect on domestic politics, as your question presumes. But I do think that you’re right to suggest that domestic politics can be a powerful source of constraint on this country’s, or for that matter, any Democratic country’s participation in war.

That’s the premise of the Democratic peace theory, which has shown itself to be quite robust when tested against the empirical evidence. And I think the historical evidence also affirms the point. The US is slow to get involved in World War II because of the power of domestic politics. Congress in 1938 comes close to passing a pacifist amendment to the Constitution. Voters can and do restrain state behavior, but I’m not convinced that violent protest is the most effective means for domestic politics to exercise that constraining effect.

[VINOD AGGARWAL] Michaela, you work on these issues a little bit.

[MICHAELA MATTES] Well, yeah. So I was going to say that I think that probably a bit more optimistic about the role of public opinion in constraining leaders, and although you sound like it, too. I mean, I’m thinking for one, the US is a special case, right? The US doesn’t have to care. Americans don’t have to care that much about the rest of the world, right? They tend to be safe from other conflicts. If you are Israel, or if you are in Taiwan, or if you’re Japan, or if you’re Germany, international politics matters a lot more to you in those countries.

And I think we’re certainly seeing in Israel, right, that there’s quite a bit of support for going after Hezbollah. And in fact, it’s strengthening Netanyahu’s government. But even in the US, right, probably one of the reasons we’re not seeing President Biden be stricter with Israel and trying to constrain their war against Hamas and now about Hezbollah, is to worry about what that will do to the election, right? I mean, Michigan is a swing state and there’s real concern about, yeah, what progressives might think, what Arab American voters might think. So I think we are seeing these things matter in some ways.