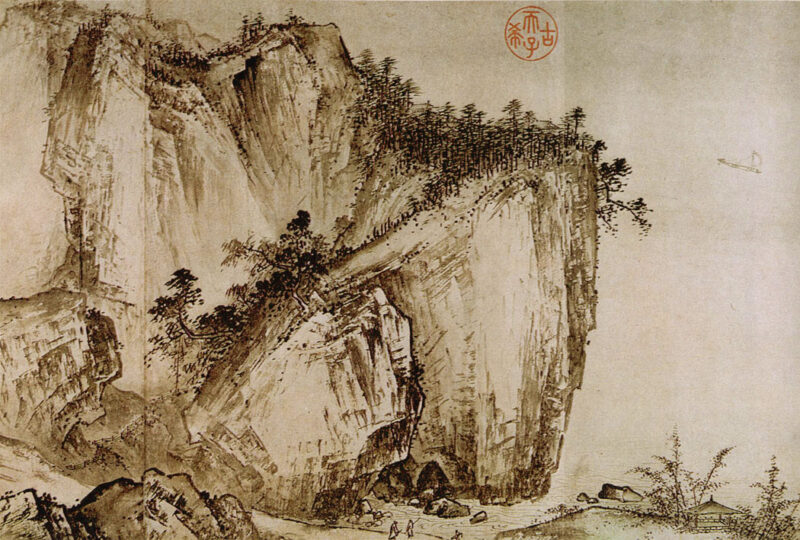

For the past four years, Jesse Rodenbiker, a Ph.D. student in the UC Berkeley Department of Geography, has traveled to China to research ecological urban planning projects. Over time, he has noticed that many of the planners responsible for ecological zoning in modern-day China rely on an ancient Chinese aesthetic concept known as shan-shui, a term made from the characters for “mountain” and “water” that is translatable as “landscape.”

Shan-shui has traditionally been expressed through landscape poetry and painting, but today the concept is finding a new medium in cities, as the concept has become part of what Rodenbiker calls the “distinctly Chinese imaginaries of sustainable urbanism.”

In 2017, Rodenbiker published “Superscribing Sustainability: The Production of China’s Urban Waterscapes,” in UPLanD, the Journal of Urban Planning, Landscape, and Environmental Design, which explores how the concept of shan-shui originally emerged in third-century Chinese landscape poetry, but now “is used to reconfigure and reimagine sustainability and contemporary China’s urban landscapes.”

In 2017, Rodenbiker published “Superscribing Sustainability: The Production of China’s Urban Waterscapes,” in UPLanD, the Journal of Urban Planning, Landscape, and Environmental Design, which explores how the concept of shan-shui originally emerged in third-century Chinese landscape poetry, but now “is used to reconfigure and reimagine sustainability and contemporary China’s urban landscapes.”

Rodenbiker’s interest in Asia dates back to his undergraduate days studying classical Indian and Chinese philosophies. After graduating, he worked for a non-governmental organization near the border of North Korea and China, where he worked closely with second and third-generation Korean-Chinese who had emigrated to China from North Korea. In the process, he developed Chinese language skills, and he later wrote for a magazine in China on environmental issues, foreshadowing his future research focus. Once he was back in the U.S., Rodenbiker worked with the Sustainable Cities Initiative and began studying geography at Berkeley. He has since made contributions to the field in both Chinese and American journals.

“I find geography so compelling in part because it’s so unabashedly promiscuous: it draws on so many different types of disciplinary research methods,” Rodenbiker said in an interview. “When I started to read geography, I found it really spoke to me. I thought, if there’s a future doing research, it would be this kind that transects the social sciences and humanities.”

For “Superscribing Sustainability,” Rodenbiker focused on two municipal ecological projects, Tangshan Nanhu Eco-City and Meixi Lake. These projects were ideal for research because of their ambitious, environmentally conscious designs, which included alternatives to automotive transportation, carbon sequestration, and material reuse. They also both provided for ample connection to nature, through habitat preservation, park space, integration of gardens, and other measures. Tangshan features a massive “Tea Island” constructed out of repurposed coal ash and a constructed wetland with over 80 species of birds, according to Tsinghua University. Meixi Lake centers the city around a 40-hectare lake; in the aerial photo on the architecture firm’s site, the lake is an attractive deep topaz.

“I show how this aesthetic concept, originally emerging in third century Chinese landscape poetry, is used to reconfigure and reimagine sustainability and contemporary China’s urban landscapes,” he explained in the publication’s abstract. “I draw on original mixed methods fieldwork, including interviews over a two-year period, digital archiving, historical texts, and discourse analysis. Through these methods, I detail the emergence of shan-shui aesthetics, then draw on the concept of superscription, the historical process of layering symbolic meanings, to understand the contemporary superscription of shan-shui with urban sustainability through the writings of prominent Chinese scientists and urban planning experts.”

Rodenbiker discovered that, while ecological zoning projects are often executed at the municipal level, the dictates for their creation come from all levels of Chinese government and society. He notes that the work of ecological scientists from the 1980s, along with the work of ecological Marxists and economists from the 1990s and 2000s, coalesced to “articulate this green development platform that now goes under the name of ecological civilization-building.”

Rodenbiker discovered that, while ecological zoning projects are often executed at the municipal level, the dictates for their creation come from all levels of Chinese government and society. He notes that the work of ecological scientists from the 1980s, along with the work of ecological Marxists and economists from the 1990s and 2000s, coalesced to “articulate this green development platform that now goes under the name of ecological civilization-building.”

The concept of ecological civilization-building is evident at the highest levels of government. In 2007, President Hu Jintao proposed the concept of “ecological civilisation” as part of the nation’s plan for economic growth, and years later, the CPC enshrined ecological civilization-building in the Party Constitution. As an article by Dr. Ben Parr and Professor Don Henry explains, “The Congress stressed that the development of ecological civilisation should be integrated into all aspects and the whole process of economic development, political development, cultural development, and social development.”

The dominance of ecological discourse is also visible in arenas of popular consumption, like TV advertisements. “It seeps into the national ethos,” Rodenbiker says. “Different branches of the municipal state communicate with state-led urban design firms. They draw on these kinds of classical imaginaries of Chinese landscape poetry and classical ink painting to derive a reputable city-planning branding rubric that operates as a sustainability fix, while at the same time doing something for the local municipal political economy, which allows cities to generate funds and generate finances to provide services.”

Chinese cities vary in their ability to respond to the central state’s requirements, Rodenbiker notes, and a complex network of different institutions has emerged to provide support. That network includes private-sector architecture firms, government officials who approve bids and sign off on projects, and the municipalities that have to clear swathes of land to make space for ecological building. Cities at a lower level in the Chinese administrative tiao kuai power matrix are able to exert power through their control and use of pieces of land. (Tiao is the vertical line of administrative authority, while kuai is the horizontal, expressing the geographic space over which an institution has local jurisdictional coverage). In this system, cities that might normally be low in the hierarchy of power have influence and jurisdiction because of their control of real estate: Rodenbiker points to cities like Kunming, Chengdu, and Dali, which are lower in the tiao but have vast lands on the kuai side, affording them myriad options for ecological zoning.

Yet while Chinese cities’ integration of shan-shui and ecological planning have spawned utopian images used for marketing, Rodenbiker notes that one element is almost always absent from these depictions: people. The beautiful mock-ups of environmentally conscious buildings almost never depict the lived experiences of residents, who are often asked to move from their homes in order to make room for new projects. Further, Rodenbiker argues, these residents have little power to define or frame the ecological civilization-building that radically shifts the ground beneath their feet.

“Residents do not make the symbolic connections connoted through superscription,” he writes. “The urban spaces designed and promoted as the shan-shui city are not recognized as such in the everyday lives of residents.” He quotes the vice-director of an urban design firm saying that local officials “have Chinese traditions in their bones” and that “utilizing shan-shui incorporates ideas, which are highly ingrained in popularized behavioral norms….” But he also quotes a resident of one of the eco-cities, who told him, “this is just another urban development project, it does not have anything to do with Chinese culture; it is a totally new construction.”

“From the lived experiences of these residents inundated with construction projects, the emergence of Tangshan Nanhu in a previously abandoned brownfield reads as banal,” Rodenbiker writes. “In this banality, the mediating veneers of digital imagery, urban plans, and municipal government rhetoric are affectively transparent enough to evade conscious recognition of living in the ‘shan-shui city’.”

As part of his current work, Rodenbiker is integrating “photo voice” (images produced by research subjects who document their lived experiences with cameras) as he investigates the nuanced consequences of displacement. Not everyone displaced by ambitious government projects experiences that displacement in the same way, Rodenbiker cautions. Varying forms of compensation and options for relocation mean that dislocation might hold disruption in one hand and opportunity in the other, depending on individual circumstance. Rodenbiker arrived at this finding through careful research he undertook in housing for residents who had been displaced by ecological civilization-building projects, and he sees opportunity for further findings in illuminating the lived experiences of everyday people.

Beyond the mountains and water of shan-shui lies a complicated new narrative, and Rodenbiker’s research is showcasing the experiences of individuals to paint a different kind of picture. Some urban planners want to use glorious shan-shui paintings from China’s past to tell the story of ecological civilization-building. But as he writes in “Superscribing Sustainability,” in this process, there is a “significant disconnect between the state framing of urban space and the lived experiences of urban residents,” and “the lack of resonance with everyday residents’ urban experience shows the dearth of power to narrativize urban development outside of state circles.”

Top photo credit: Xia Gui, work in Public Domain, Wikimedia Commons.

Inset photo credit right: Master plan for Nanhu Eco-City in Tangshan, ISA Internationales Stadtbauatelier, Creative Commons 3.0 Germany License