Tourists headed for a picturesque weekend in California’s wine country often careen across the Richmond Bridge expecting waterfront views, only to encounter an enormous prison. Located less than twenty miles from San Francisco, San Quentin State Prison is the only prison in the state to house and execute death row inmates. But like every other prison in the state, it is grossly overcrowded, typically operating at 200-300% capacity. Courts have ruled that these prisons threaten the safety and health of its occupants, raising a haunting question: do the conditions of American prisons constitute torture?

The question of whether California’s modern prison system is constitutional lies at the heart a new book by Berkeley criminologist Jonathan Simon, Mass Incarceration on Trial: A Remarkable Court Decision and the Future of Prisons in America (New York: New Press, 2014). Simon long ago established himself as an expert on the quantifiable changes in American penology, authoring two prize-winning books. Yet when he moved to California to teach in the School of Law and the Program in Jurisprudence and Social Policy at UC Berkeley, he was struck by how numbers failed to represent the inhumanity of the state’s prisons, or as he explained in an e-mail interview, “how miserable the conditions, how extensive the overcrowding, how deep the level of medical neglect and suffering, how severe the unmet need for psychiatric care.”

The 60th anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights further motivated Simon. “Like many U.S.-centered students of law and society, I tended to think about human rights abuses as a problem happening somewhere else,” he explains. “If the U.S. was engaged in something like that, it was in places like Guantanamo.” A year at the University of Edinburgh allowed Simon to explore the investigatory agencies and regulations that ensure humane incarceration practices in Europe, and led him to ask why there were no such institutions in the United States.

In Mass Incarceration, Simon carefully reads several recent U.S. court decisions that affirmed the basic humanity of prisoners and condemned prisons for violating the standards of humane punishment. From these readings, Simon concludes in his book that “mass incarceration is inherently unconstitutional.”

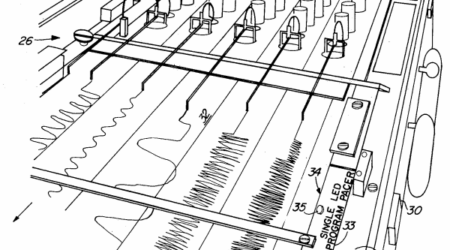

How did the modern justice come to violate the law it is meant to uphold? Simon’s narrative begins with penal reforms put in place in the 1970s that treated prisoners like medical patients, catalogued in a comprehensive data system. New state-of-the-art prison architecture projected an image of order and humanity that appeased experts and ordinary citizens alike.

Prisons have become places of extreme peril, not from violence per se, but because of the chronic overcrowding, regular lockdowns, and medical neglect.

Yet the reform and expansion of the prison system veiled its worst offenses. An ethos of “total incapacitation” transformed the role of the American prison from that of a safeguard against society’s most violent offenders into an instrument to prevent violent crime altogether. An emerging common sense dictated that prisons were, as Simon writes, a “humane way to prevent crime by keeping a largely incorrigible population safely separated from the general public.” New criminal laws called for the imprisonment of petty drug offenders, transforming a once-modest count of violent felons into a ballooning number of mentally ill, non-violent addicts. These convicts aged into a geriatric, chronically ill population that prisons failed to tend.

One recent decision carries particular weight for the future of the mass incarceration regime. In 2009, a special three-judge trial ruled in a landmark case that California must reduce its prison population by 40,000 inmates—more than the entire size of the state prison population in 1970. As Simon explains, “the court went beyond talking about conditions and pointed the finger squarely at laws and policies that drive overcrowding and indifference.” When the state appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court in 2011, a 5-to-4 ruling not only upheld the order, but also denounced California’s prison system as a humanitarian crisis. The majority opinion decried the state’s incarceration practices as “incompatible with the concept of human dignity” and fundamentally uncivilized. Through this decision, these cases “had, in effect, put mass incarceration on trial” and illuminated “a way out,” Simon explains, noting that the “way out” requires changing the conventional wisdom about incarceration in the U.S.

“Popular culture imagines prisons as places of austere control,” he says, while “legal elites tend to imagine prisons as places where, as the Supreme Court put it in 1994, ‘dangerous men are held securely in humane circumstances’,” Simon writes. Instead, he says, prisons have “become places of extreme peril, not from violence per se, but because of the chronic overcrowding, regular lockdowns, and medical neglect. These were not places of law, but of emergency governance and gang rule.”

As these abuses come to light, “chastened citizens [will] radically expand their vision of humanity,” Simon predicts. He foresees an impending revolution in common understandings of prisoners’ rights that will transform American penal codes.

“I hope,” he says, “that my book will advance that recognition.”