In Fall 2014, Nancy Scheper-Hughes, Professor of Anthropology at UC Berkeley, and Sam Dubal, MD/PhD candidate (Harvard Medical School/UCSF-UC Berkeley), co-organized a Social Science Matrix seminar called “Envisioning Radical Experiments in Social Science and Clinical Medicine.”

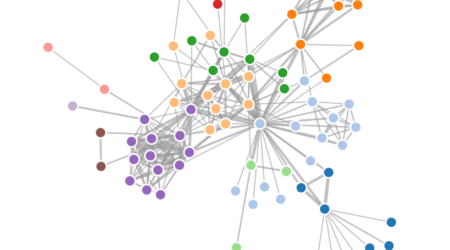

This seminar sought to bring together not only scholars from multiple disciplines (including public health, clinical medicine, anthropology, sociology, history, geography, information, economics, comparative literature, public policy, and social work), but also physicians, psychiatrists, patients, and community members, with a goal to create “a collaborative crucible for a new form of medical practice,” Dubal explains. “We ask: how can we envision and design innovative ways of addressing inequities and inequalities in clinical medicine, as informed by critical theory as well as clinical and personal experience?”

Scheper-Hughes explains that her interest stems from longstanding concerns with the criminalization of poverty and madness based on her research on the relationship of ‘schizophrenia’ and historical traumas (e.g. the ‘Great Famine’ in Ireland, and dislocation, camp life, and genocide during and after WWII) and the presence of the severely psychotic in prisons and jails in the U.S. Her work in radical psychiatry was strongly influenced by psychiatrists who were willing to question the norms of biomedicine and come to the aid of the so-called “criminally insane”.

Dubal is completing his dissertation on the reintegration of former militant rebels in northern Uganda; based on his work, he has developed a “deep suspicion of a philosophy of humanism that serves as the lynchpin for humanitarian intervention,” as he explains, and maintains “an enduring concern with the hegemony of liberal humanist philosophy as a paradigm of care in clinical medicine, and the way in which it depoliticizes clinical care.”

“We teach our clinicians to care for the individual suffering of the patient in front of them,” he says, “but we don’t teach them to care for or about a politics which generates social suffering.”

From Radical Psychiatry to Community Health

One of the goals of the seminar, says Scheper-Hughes, is to create a dialogue among “critical psychiatrists, critical anthropologists, ethno-psychiatrists, critically engaged psychiatric social workers, and other providers, together with the psych-survivor community,” who share a “strong sense of dismay at the failures of the dominant psychiatric paradigm that reinforces cognitive and emotional differences by reducing them to ever-changing and refashioned diagnoses and submitting them to powerful and often damaging drug regimes.”

Another theme: the search for autonomous solutions to local crises that stem in part from economic and medical globalization. “Sam and I are both dissatisfied with the global health agendas: the humanitarian aid that is a Band-Aid for diseases caused by poverty, political conflict, violence,” Scheper-Hughes says. “We are looking for solutions beyond “drugs for all” and “Doctors without Borders”, etc.” We hope to identify solutions that acknowledge and respond to the sick-making issues of institutionalized racism, economic inequality, environmental exploitation, gender violence, and other forms of injustice and inequality that manifest themselves in the clinical encounter.”

The two anthropologists witnessed first-hand the clinical care-delivery challenges facing local communities in Spring 2014, when they visited Timbauba (pop. 55,000), in Northeast Brazil, where Scheper-Hughes has conducted multi-decade anthropological research. While participating in a training session for 120 community health agents (local citizens trained by the state to provide basic medical services in the absence of resident doctors), they heard complaints such as, ‘We are frustrated,’ ‘We have the most difficult job with no backup,’ and ‘We don’t know what we will run into when we walk inside a home. Sometimes it is a raving madman or a violent drug dealer, and sometimes it might be a woman in labor without time to get her to a public hospital in Recife [the capital city].”

Scheper-Hughes served as a community health agent in Timbaúba during the 1960s, when she delivered babies, immunized babies, administered injections, treated infectious diseases (TB and schistosomiasis), and bandaged wounds. “Today’s community health agents are not allowed to put salve on a baby’s skin, let alone to ‘catch’ a baby,” Scheper-Hughes says. “The poor people living in hillside slums (favelas) in the area are forced to either travel to the capital for a pre-arranged C-section or to give birth at home just as their grandmothers once did because there are no resident obstetricians in the public health sector.”

Through their Social Science Matrix seminar, Scheper-Hughes and Dubal brought together an array of perspectives to find solutions to such challenges. “We realized that to be able to transcend the limit of existing interventions on healthcare inequalities, we needed a different approach—one based in praxis and organized by horizontal collaboration,” Dubal says. “We could not rely on the experiences of patients and physicians alone, relatively detached from critical theory; nor could we base our interventions on the dizzying theories of critical scholars, relatively detached from lived experience….We are united by a common goal of creating a social medicine proper: a healing of the illnesses of not only individual patients but also society itself. Our approach to this goal, and the central problem of this seminar, is to co-design possible experiments whereby critical theory may come to inform clinical practice.”