Achievement gap. Racial prejudice. Microaggressions. These terms are frequently thrown around in the media, but for many minority students, they are an everyday reality.

Rodolfo Mendoza-Denton, Professor of Psychology at UC Berkeley, conducts research to pin down the long-term effects of racial bias and stereotypes in the classroom. His work focuses largely on minority students at the university level, and examines factors that affect students’ achievement and emotional health.

Providing support for minority students at universities is important, Mendoza-Denton says, because when students are a part of a stigmatized minority, their campus experience can lead to questions about belonging and acceptance. This can have far-reaching consequences: it may influence students’ future identities and career decisions. When a minority student does choose to enter a field in which s/he is underrepresented, he explains, it “brings up questions and ambiguity about one’s status, and whether you can see yourself making a career in that kind of context.”

Mendoza-Denton and colleagues in the UC Berkeley Relationships and Social Cognition Lab are not alone in examining the effects of stereotyping in higher education. Many classic social psychology studies have demonstrated the effects of negative stereotypes. In a 1995 study, psychologists Claude Steele (currently Berkeley’s Executive Vice Chancellor and Provost) and Joshua Aronson examined test-taking by White and African-American students in two conditions. For the first test condition, researchers told student participants that the test was merely to study psychological factors in problem solving. But for the second condition, students were told that the test measured intellectual ability. Under the first condition, White and African-American students performed equally well. However, when told that the test measured intellectual ability, African-American students performed less well than their White counterparts. This phenomenon is known as stereotype threat and has been linked to students’ concerns about fulfilling negative stereotypes.

Mendoza-Denton and colleagues in the UC Berkeley Relationships and Social Cognition Lab are not alone in examining the effects of stereotyping in higher education. Many classic social psychology studies have demonstrated the effects of negative stereotypes. In a 1995 study, psychologists Claude Steele (currently Berkeley’s Executive Vice Chancellor and Provost) and Joshua Aronson examined test-taking by White and African-American students in two conditions. For the first test condition, researchers told student participants that the test was merely to study psychological factors in problem solving. But for the second condition, students were told that the test measured intellectual ability. Under the first condition, White and African-American students performed equally well. However, when told that the test measured intellectual ability, African-American students performed less well than their White counterparts. This phenomenon is known as stereotype threat and has been linked to students’ concerns about fulfilling negative stereotypes.

Stereotype threat has generated a substantial body of research. Mendoza-Denton has contributed by highlighting the importance of social climate and relationships. For this work, he often refers to the “four Rs” of academic achievement; noting that people are familiar with the first three (‘reading. ‘riting ‘rithmetic), Mendoza-Denton stresses the fourth, relationships, in his research.

For example, in a 2002 study, Mendoza-Denton and colleagues tracked how student concerns about being targets of discrimination on college campuses translated to a lack of belonging. The research team was also interested in how students avoided contexts where they might be discriminated against. When these contexts include classes and professors, Mendoza-Denton notes, minority students are at a disadvantage, as they are diverting attention away from learning toward vigilance. The result, Mendoza-Denton shows, can be underperformance.

To make matters more complicated, racism can often be covert and ambiguous. “The complexity of addressing prejudice is that it has an explicit and an implicit, sometimes unconscious manifestation,” Mendoza-Denton says. Consider a 2003 study from the National Bureau of Economic Research that sent fictitious CVs in response to real job postings. The CVs were assigned typically African-American-sounding names or typically White-sounding names. For highly qualified applicants, this did not matter: the researchers found that they were awarded the job regardless of race. But between two mildly qualified job applicants, the White applicant was more likely to be awarded a position than his/her minority counterpart. This was the case even for those listings that claimed equal opportunity employer status in the advertisement.

“We’re in the thick of the struggle, and you can’t achieve a new normal without that struggle.”

At the university level, racial bias can affect more than test scores and choice of major. In his most recent work, Mendoza-Denton has discovered higher rates of inflammatory processes, or the body’s physical reactions to stress, in otherwise healthy undergraduates, a finding he attributes to concern about discrimination as well as stereotype threat. Seemingly innocuous interactions, such as professor-student meetings, can be anxiety-inducing for some students who fear discrimination.

Although his research suggests that racial bias may be deeply rooted in educational institutions, Mendoza-Denton believes that there are solutions. He focuses in part on providing more effective training for teachers, professors, and mentors on how bias can creep into student evaluations and mentorship.

Indeed, Mendoza-Denton’s research has shown that minority students are less likely to receive the type of mentorship that is vital to their success in higher education. Too often, he notes, teachers will give up on students due to perceptions of inability or lack of preparedness. This only leads to a confirmation of this expectation without giving the student a chance to grow and develop. Effective mentorship, he notes, should not be available only to a chosen few.

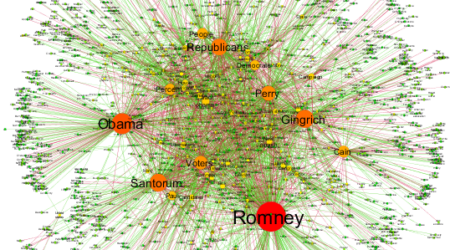

As a result, Mendoza-Denton stresses the importance of mentorship and interaction in friend groups. Supportive, positive peer networks can affect a student’s sense of belonging at a university. For example, in one recent study, Mendoza-Denton and colleagues found a positive effect of ethnic theme houses on students’ well being. He has also documented positive effects of cross-race friendships, suggesting that the wider someone’s social network, the more likely that individual is to feel connected and at home within a university. A diverse social network is important to feeling a sense of comfort in different campus spaces, the research has found.

More than 60 years after Brown v. Board of Education, the landmark Supreme Court case that integrated public schools in the United States, researchers are still unearthing the effects of racial bias upon minority students’ academic achievement at all levels of education. But Mendoza-Denton remains confident that, even given the slow pace of progress, a more egalitarian future lies ahead. “We’re in the thick of the struggle” he says, “and you can’t achieve a new normal without that struggle.”

Photo Credit: CC 2.0, via Flickr: John Morgan, “People of Berkeley – Meeting Place“. Image modified from the original.