Maps. Sculptures. Lecture halls. Art galleries. Ballet classes. Parades. Concrete blocks. Bodies splayed over stairs. Community gardens filled with tires. The genre of “p[art]icipatory urbanisms” describes a range of art forms, practices, and institutions that invite us to think creatively and critically about urban space, community building, activism, and artmaking in the contemporary city. Examples range from the Khirkee Hip-Hop Community Center in New Delhi, India, where youth find a creative outlet in art forms like breakdancing, to the Ciclistas Bonequeiros, or “puppeteer cyclists” of São Paulo, Brazil, who stage idiosyncratic performances with puppets made of recycled materials staged in diorama-style boxes mounted on bicycles.

Now anyone with internet access can engage with dozens of projects of this variety, thanks to P[art]icipatory Urbanisms, an innovative collaboration by UC Berkeley graduate students Kirsten Larson (from the Department of Architecture and City Planning) and Karin Shankar (from the Department of Theatre, Dance and Performance Studies), whose work was supported by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation’s Global Urban Humanities Initiative.

Since debuting last fall, this project has received thousands of hits (more than 4000 in the first week alone), articles have been reblogged and reposted numerous times, and Larson and Shankar have heard from several academics saying that they will be using the anthology in their research and teaching. Larson and Shankar are also planning to curate an exhibition based on this work in São Paulo this fall.

The stylized, bracketed title of P[art]icipatory Urbanisms highlights the project’s interest in blurring the boundaries between aesthetics and politics, whether the subjects in question are performance collectives, educators, collectors of e-waste, or community journalists. “Given the multitude of arenas in which participatory urban activity has been proliferating in the past two decades—including within a range of public, private, civil society, and hybrid formations—participation itself, as mode of engagement, is a critical terrain of negotiation between state, society and market forces,” Larson and Shankar observe in a co-written introductory essay.

There are two parts to the project. The first is a collection of interviews conducted with urban practitioners and artists (broadly defined) in the cities of New Delhi, India, and São Paulo, Brazil. These cities were chosen both because of the project curators’ respective backgrounds in South Asian and Brazilian urbanisms, and, as noted on the project website, because of their similar sizes and “positions in global urban imaginations and political economy.”

The second part is a peer-reviewed anthology of articles divided into four sections: “Memory and the City-Body”; “Austerity Politics, Occupation, and Performance”; “Curating Publics”; and “Ruptures in Neoliberal Space.” The anthology takes readers to and through Port-au-Prince bidonvilles, or shantytowns, in Haiti; street protests in Madrid and Rome; art installations in the Black Sea port town of Batumi, in Georgia; and numerous other cities, including New York City, Shanghai, Guangzhou, San Francisco, and Zurich.

The interviews, collectively titled “Urbanismo Participativo/ Participatory Urbanisms,” are displayed online in a carefully designed diptych, a conceptual form used in visual art to extend canvases and draw parallels. Readers also have the option of downloading the interviews as a 143-page publication. This PDF version presents the interviews one at a time, but reproduces the effect of the diptych by offering Portuguese and English translations displayed side by side.

The interviews, collectively titled “Urbanismo Participativo/ Participatory Urbanisms,” are displayed online in a carefully designed diptych, a conceptual form used in visual art to extend canvases and draw parallels. Readers also have the option of downloading the interviews as a 143-page publication. This PDF version presents the interviews one at a time, but reproduces the effect of the diptych by offering Portuguese and English translations displayed side by side.

“We chose [the form of the diptych] so that readers and interviewees from the two cities could form unexpected connections,” Shankar said in an interview.

Such juxtapositions invite audiences to read between and across Komita Dhanda and Suddhanva Deshpande’s street plays of personal narratives of industrial workers, at IG Khan Memorial in Aligarh, India, on the one hand, and Brazilian graffiti muralists pioneering the practice of “Cartograffiti,” on the other. Each interview also includes a number of arresting photographs, such as the image of Mauro Neri da Silva reproducing the posture of a trash-bin sculpture of a man, chin raised to the sky in a posture of almost yogic supplication, on the edge of the Billings Reservoir, in the Grajaú region of São Paulo.

The interviews, Larson and Shankar note in a joint preface to their publication, “map the multiple and disjunctive ways in which ‘participation’ is enacted…. [They] trace how these urban actors create politico-aesthetic ruptures; experience and experiment with the material and affective force of participation; leverage its power to potentially reshape urban space; and contend with the limits of participatory working processes.”

This ambitious project statement is fulfilled by the scope and scale of the work itself. The interviewers, including both Larson and Shankar as well as a number of research assistants, elicit provocative, deeply thoughtful reflections on the intersections of time and space, the performance of collectivity, the fact of urban multiplicity, pedagogical practice, voice, mediation, and the relationship between individual city dwellers and city infrastructures. Interviewees reflect on challenging issues of urban informality and inequality—on the fact that, in the words of Ravi Vasudevan of the SARAI Collective, people live in these cities “despite not being allowed to have all sorts of things that they should be allowed to have.”

This ambitious project statement is fulfilled by the scope and scale of the work itself. The interviewers, including both Larson and Shankar as well as a number of research assistants, elicit provocative, deeply thoughtful reflections on the intersections of time and space, the performance of collectivity, the fact of urban multiplicity, pedagogical practice, voice, mediation, and the relationship between individual city dwellers and city infrastructures. Interviewees reflect on challenging issues of urban informality and inequality—on the fact that, in the words of Ravi Vasudevan of the SARAI Collective, people live in these cities “despite not being allowed to have all sorts of things that they should be allowed to have.”

The emphasis in each interview is the concept of “praxis,” which Shankar defines as “a being, doing and knowing.” As she explains, “the artist collectives, waste worker collectives, graffiti muralists, and other groups that we have interviewed define, enact, and create knowledge about a multitude of ways in which to effectively ‘take part’ in the cities of New Delhi and São Paulo. In São Paulo, for instance, Coletivo Pi, a feminist dance collective, is thinking about how to create urban kindness through their movement and dance works…. Graffiti muralists from the collective Imargem, in the periphery of São Paulo, are thinking about how graffiti may provide an alternate itinerary through the city. In New Delhi, a media collective in a working class neighborhood thinks about urban citizenship as a sense of ‘belonging’; a dance collective is working towards creating a ‘dance ecosystem’ . . . These present different and generative ways of thinking, doing, and knowing about urban participation.”

Of course, not all of the interviewees agree on the key terms of the larger project—including “publics,” “counter-hegemony,” “agonism,” “memory,” “occupation,” “participation,” “infrastructure,” and “cooptation”—and that is half the fun of hearing their ranging perspectives. Shankar points out that at least two different views of “urban citizenship” emerge from interviews with a waste workers’ collective in New Delhi and a media collective in a working class neighborhood. For Bharati Chaturvedi in Chintan, New Delhi, urban citizenship is “when everybody has a basic standard of living, and can access the city, whether it’s the park, the metro station . . . urban citizenship is about how and where you are able to contribute to the city and whether the city administration facilitates . . . or allows you to contribute.” By contrast, for SARAI’s Vasudevan, questions of “rights and entitlements” lead to “a limited notion of citizenship.” Citizenship, he says, “is also about belonging; you are here in the city and so the city is yours. Now, that’s a different order proposition, and a much more interesting one.”

P[art]icipatory Urbanisms also includes a peer-reviewed, 156-page anthology of articles, which features both traditional journal articles and five formally experimental articles that perform urban scholarship in new ways, including a manifesto for “a liberatory black spatial politics”; a photo essay on a wrestling rink in Gurgaon, India; and a personal essay about the democratic politics of basketball played on a public court in Oakland, California.

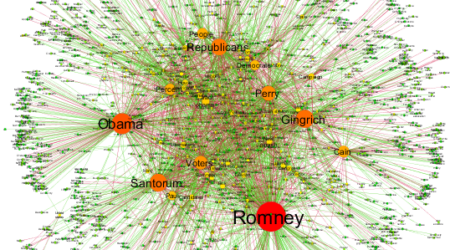

In the instructive introductory essay to the edited volume, Larson and Shankar link this work to other contemporary movements, “from Occupy (2011) to Tahrir (2011) to São Paulo (2013) to Taksim (2013) to austerity protests in Southern Europe and Greece (2014-) to #BlackLivesMatter (2014-).” This genuinely global view of relational art practices, urbanisms, activism, politics, and aesthetics (as in its older meaning, they note, “as simply ‘perceptible to the senses’”) is matched by scale and scope of the articles themselves. For example, Kavita Kulkarni’s “Ruptures in Neoliberal Space” examines ‘Soul Summit,’ an open-air house music dance party that has been held since 2001 in the historically black, rapidly gentrified neighborhood of Fort Greene, in Brooklyn, New York. Larson and Shankar especially appreciate how this work “explores the political potential of the various assemblages (both ‘live’ and in social media) of open-air house music culture . . . and how, through various forms of participatory co-production, Soul Summit works to counteract ‘the spatiality of peripheralization’ and the ‘temporality of extinction’ imposed on black social life in the [United States].”

Shankar recalls being particularly moved by two of the articles in the “Austerity Politics, Performance, and Occupation” section, which emerged from participant ethnographic research in Athens and Madrids. She and Larson describe these essays thus: “[They] present urgent and vivid ethnographic accounts of the urban manifestations of radical democratic responses to Europe’s contemporary austerity regimes. Andreea Micu’s reading of the affective forms of protest around ongoing housing struggles in Rome and Madrid identifies ‘indignation’ as the prevailing affect in times of austerity…. Her article] explores how this affect is mobilized to powerful effect in street protests…. [Gigi Argyropoulou’s article] describes how emergent and collective participatory practices in the occupied [Embros theatre in Athens during the debt crisis] may have faced repeated failures, but succeeded in marking a paradigm shift, thereby opening up the space of possibles for alternate ‘instituent’ practices of politics and culture in times of austerity.”

Shankar recalls being particularly moved by two of the articles in the “Austerity Politics, Performance, and Occupation” section, which emerged from participant ethnographic research in Athens and Madrids. She and Larson describe these essays thus: “[They] present urgent and vivid ethnographic accounts of the urban manifestations of radical democratic responses to Europe’s contemporary austerity regimes. Andreea Micu’s reading of the affective forms of protest around ongoing housing struggles in Rome and Madrid identifies ‘indignation’ as the prevailing affect in times of austerity…. Her article] explores how this affect is mobilized to powerful effect in street protests…. [Gigi Argyropoulou’s article] describes how emergent and collective participatory practices in the occupied [Embros theatre in Athens during the debt crisis] may have faced repeated failures, but succeeded in marking a paradigm shift, thereby opening up the space of possibles for alternate ‘instituent’ practices of politics and culture in times of austerity.”

Reading the essays from the anthology, I was struck not only by the quality of the interventions, luminosity of the prose, and genuine interdisciplinarity of the work as a whole, but also by all the ways in which the anthology—like the curated interviews—is itself a participatory, collaborative work of art, an artifact not only of scholarly research but citizenly and neighborly love. The artist Pâmella Cruz’s description of Brazil-based Coletivo PI might very well also apply to Larson, Shankar, and their scores of collaborators and co-creators as well: plainly, they “believe in the possibility of positive transformation”; of using scholarship to “establish affectionate relationships, relationships of real complicity, of getting to know and not being afraid of the other, the unknown, the faraway.”

The sheer plenitude of P[art]icipatory Urbanisms is worthy of celebration. That the project is also deeply critical yet hopeful, attuned to global urban inequalities yet redolent with possibility, and celebratory of the lives, aspirations, artworks, frustrations, and conceptualizations of men, women, and children from cities around the world, is worthy of wide dissemination, animated discussion, and the praxis of close reading.

Images: Courtesy of Karin Shankar. All rights reserved.

Top Image: Performance and theater collective, Companhia Antropofágica’s, walks with a Karroça (stage cart) performing street plays in the city, 2011.

Image 2: A Jana Natya Manch (People’s Theater Form) performance in Jhandapur, Delhi, 2013.

Image 3: Artist Amitabh Kumar paints a mural for a Khirkee shopfront, Khoj Artist Workshop, Delhi, 2012.

Image 4: Actors from the performance collective, Coletivo Pi, walk down São Paulo’s Avenida Paulista dressed as “petrified” executives, covered in clay and blindfolded, 2015.