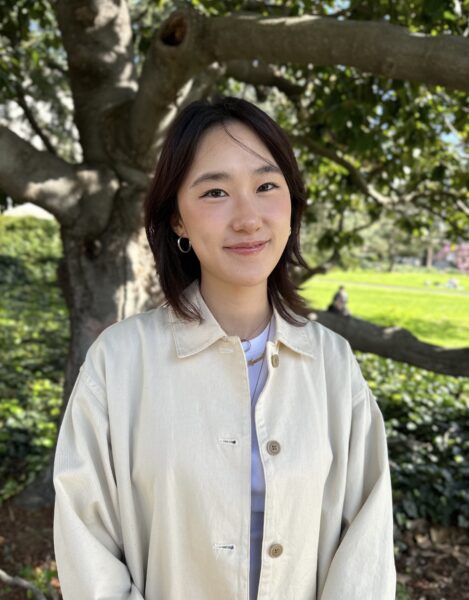

Korean beauty products, or “K-Beauty,” are not only a part of the beauty industry, but part of a long legacy of the Korean War. For this visual interview, Matrix Postdoc Julia Sizek interviews Claire Chun, a Ph.D. candidate in the UC Berkeley Department of Ethnic Studies with a Designated Emphasis in Women, Gender and Sexuality Studies, about her work on the industry and its history. Chun’s research explores how modern conceptualizations of “Korean” and “Asian” beauty, wellness, and aesthetics are shaped by overlapping forces of U.S. militarism, tourism, and humanitarianism.

Korean beauty products, known popularly as K-Beauty, has not only become a multi-billion dollar industry, but has become one of the cornerstones of international beauty products. Your work situates K-Beauty in a particular context: the legacies of the Korean War. What can we learn from looking at the rise of K-Beauty alongside that of a war that was never formally ended?

For many of us, the word “K-Beauty” immediately surfaces images, ideas, feelings, and maybe even fantasies. These images might range from cosmetic and skincare products to the poreless faces of Korean celebrities to familiar phrases like “10 step skincare routine” or “glass skin.” We might feel good, secure, and assured when thinking about K-Beauty.

In fact, in a 2021 article, “What is K-Beauty? Here’s Everything You Need to Know,” women’s lifestyle magazine ELLE confidently asserted that K-Beauty is “the secret to looking as luminous as is humanly possible.” Now a permanent mainstay in our “global beauty lexicon,” K-Beauty is no longer simply defined by skincare and beauty products, but has come to signify a larger ecology of embodied and mediated desires, practices, actors, and aesthetics. My research argues that the otherworldly luminosity promised by K-Beauty is much more than a qualitative description of the skin. But what kinds of promises does Korean luminosity extend?

In my research, I am really interested in thinking about what such promises and their failures might reveal about the fantasies and anxieties that shape not only global beauty markets, but also Korean modernity, the social life of war, and everyday practices of bodily rehabilitation. In other words, my project moves away from the question of “what does beauty look like?” to “what is beauty doing?” and “what does beauty require?”

Although cosmetic industries have been pivotal in the meteoric rise of global Korean visibility since the turn of the 21st century and throughout the ongoing accelerating militarization of the Korean peninsula and the Pacific, the bulk of critical scholarship on U.S. empire and militarism has not considered beauty practices and body politics very expansively. I think in many ways it is Korean beauty’s oversaturation in global media discourses that has occluded a more rigorous examination of its stakes. My dissertation, “Beauty Ecologies: War, Wellness, and the Aesthetics of Repair,” wrestles with this scholarly gap and explores how beauty and wellness are vital sites of racialized war-making and alternative sense-making.

Here, I’m really interested in expanding our commonsense understanding of beauty as simply a set of aesthetic standards or consumer products or industry trends. Instead, my thinking is aligned with that of other critical beauty studies scholars such as Thuy Linh Nguyen Tu, Mimi Nguyen, S. Heijin Lee, Vanita Reddy, and Genevieve Clutario, who really push us to take beauty seriously as an animating force, an “imperative discourse” (Nguyen); as that which “[holds] out hopes for vitality, for life itself” (Tu); and as a “set of narratives and practices that map forms of Asian modernity” (Lee, Moon, Tu).

Against the backdrop of the unended Korean War (a peace treaty was never signed, leaving the two Koreas in a suspended stalemate to this day), my own thinking and theorizing builds on these formulations to offer a reading of beauty as fundamentally a question about managing life in war. From South Korean plastic surgery’s wartime origin in U.S. medical humanitarian aid, to the rapidly expanding state-sponsored wellness tourism industry and intensifying militarization of Jeju Island, to discourses of transgenerational trauma and healing in Korean diasporic expressive culture, my research explores how beauty gets recruited, consolidated, and distributed in terms of repair.

In some ways, plastic surgery began literally as repair, in the context of the Korean War. How did plastic surgery rise in Korea?

The history of plastic surgery in Korea is a history of war. As scholars such as S. Heijin Lee, So Yeon Leem, John DiMoia, and Alka Menon have traced, the practice and consumption of plastic surgery in Korea emerged during and in the immediate aftermath of the Korean War. Indeed, plastic surgery as a field of surgical science developed to meet the needs of repair in the wake of two World Wars that left soldiers and civilians disabled and disfigured. Plastic surgery techniques thus had to innovate to treat unprecedented scales of debilitation wrought by new weapons of war, including severe burns and facial disfigurement caused by chemical warfare and artillery fire.

What interests me about the history of plastic surgery in Korea, however, is the ways in which reconstructive and aesthetic surgery were explicitly doled out as global humanitarian aid efforts by the U.S. military during the Korean War, whereby military surgeons performed cosmetic procedures alongside reconstructive surgeries for combat victims and civilians alike. It’s the very slippage between the reconstructive and aesthetic that I’m especially concerned with, specifically within the contexts of the unended Korean War and ongoing U.S. military occupation of Korea. When we reframe beauty within the terms of debility and repair, how does that change its stakes?

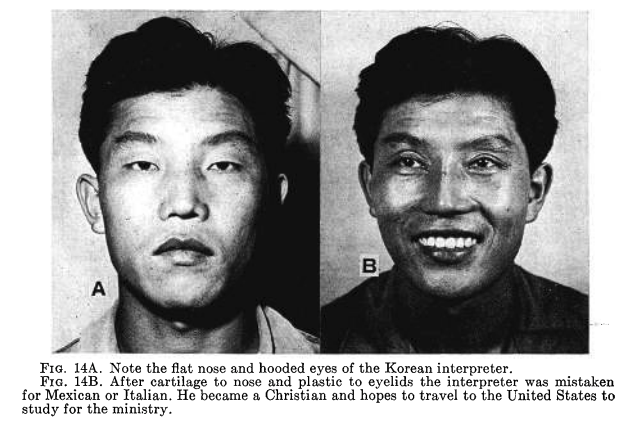

Many English language accounts credit the modern practice of cosmetic surgery in Korea to Dr. D. Ralph Millard, who served as Chief Plastic Surgeon to the U.S. Marine Corps during the Korean War. Having written on his experience in Korea, Millard reveals in his published medical literature the humanitarian impulse behind distributing plastic surgery as a form of American benevolence: “One of the purposes of the U.S. Marines remaining in Korea after the ceasefire was to assist the war-ravaged people in their rehabilitation. It seemed that plastic surgery should be a part of this project and through it would be constructed visible evidence of American goodwill in Asia.” There’s something really significant here about the ways that Millard formulates rehabilitated Korean bodies as “visible evidence” of America’s so-called “goodwill.” This formulation reveals how vital the visuality of repair, which I argue is also to say beauty, is to legitimizing the project of American military occupation and empire-building.

Indeed, much of Millard’s published literature about his work in Korea hinges on “before” and “after” portraits that reveal a remarkable transformation. One such makeover that widely circulates in relation to Millard’s legacy is that of a Korean interpreter (pictured above) who in Millard’s words, “came in requesting to be made into a ‘round-eye.’” According to Millard’s account, this Korean man hoped to migrate to the United States but was concerned that the “squint in his slant eyes” made him appear inscrutable and thus distrustful to white Americans.

The explicitly racialized motivations informing Millard’s surgical practice during the immediate post-war period are important to understanding how racial ideologies scaffolded ideas of aesthetic repair. Indeed, Millard referred to his cosmetic surgical work in Korea, the bulk of which was most concerned with widening the eyes through surgical incisions and sutures on the eyelid, as “deorientalizing.” As such, the blepharoplasty procedure (colloquially known as double eyelid surgery) has become almost synonymous with Korean plastic surgery, despite its 19th-century origins as a reparative procedure.

However, while Millard is often credited with introducing and popularizing the blepharoplasty procedure in Korea, John DiMoia and Alka Menon further contextualize the development of Korea’s plastic surgery industry by pointing to the regional forces that also shaped cosmetic surgical procedures before the Korean War. In particular, they underscore the development of surgical techniques in Singapore and Japan prior to Millard’s arrival in Korea which, as they argue, informed his own practice as well as the development of a regional Asian aesthetic. And so, I’m really interested in paying attention to these overlapping forces, as plastic surgery in Korea is fundamentally entangled in transnational and regional circuits of aesthetics, medicine, war, and empire.

Today, the figure of plastic surgery in Korea seems very different from its origins. The popularity of plastic surgery in Korea has led to the coining of a phrase translated to “plastic surgery monster,” which describes someone whose plastic surgeries have rendered them into a grotesque figure. What is a “plastic surgery monster”?

As I mentioned earlier, K-Beauty likely produces positive feelings for the average consumer. We feel reassured, maybe even hopeful. But just as quickly as we are able to imagine the aspirational fantasies of clear skin, we might also be reminded of the seemingly terrifying excesses of such desires for beauty, most notably in the form of plastic surgery. Since the turn of the 21st century, South Korean plastic surgery consumption has saturated global media discourses, inciting fascination and horror among Western and Asian audiences alike. We’ve likely encountered Western news media articles with spectacular titles like, “Victims of Craze for Cosmetic Surgery” or “South Korea’s Growing Obsession with Cosmetic Surgery” that stoke the flames of hysteria. And even in Korea, online users have coined a term, sung-gui, which directly translates to “plastic surgery monster.”

Explicit in its naming, the term, which first began circulating in the early 2010s, describes a person who has undergone excessive cosmetic alteration to the extent that their postoperative body looks highly artificial and indeed, grotesque. In Korea, there are recognizable features of a plastic surgery monster which, as So Yeon Leem details, includes a “convex forehead, overly wide eyes and thick eyelids, a long and protruding nose, an awkwardly shaped mouth, and an excessively small jaw.” We can see in the illustration above a caricaturized representation of these very features. As both Leem and this illustration demonstrate, the plastic surgery monster is marked by a mimetically formulaic appearance that has been criticized as “cheap-looking,” “unpleasant,” and “unnatural.”

Body modification by way of plastic surgery has long been a source of visual disorientation, repulsion, disgust, and even terror. As the global media response indicates, the seemingly otherworldly contortions of skin, flesh, cartilage, and bone continue to provoke acute anxieties about race, gender, and the body. Against this backdrop, what really interests me about the label “plastic surgery monster” is the implied accusation that body modification deemed excessive is explicitly monstrous. How do we measure excess in this context? What are the metrics of monstrosity?

The very category of “monster” warrants a thorough analysis — which I can’t provide here in this interview, but have written about in my published work — as the history of racialized bodies organizes the discourse of monstrosity. Scholars like Jack Halberstam and Fatimah Tobing Rony track the ways in which the “monster” is racialized as a “foreign alien” and “taxidermic specimen.” Thinking with Halberstam and Rony, I want to know more about what exactly is monstrous about the surgically modified Korean woman. How does her monstrosity shift and signify differently in different places and historical moments? And thus, what kind of warning is the condemnation of her aesthetic pursuits meant to provide? In other words, what should we be afraid of?

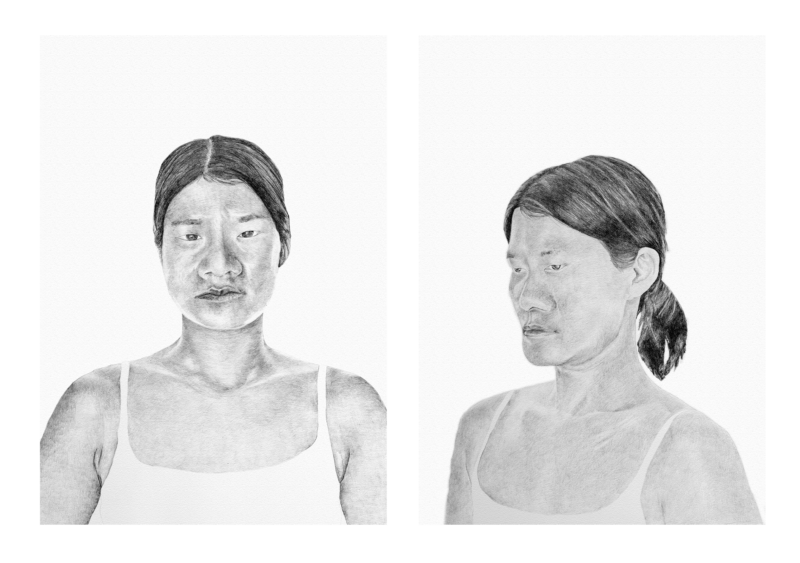

To understand this phenomenon, you look at the work of Mirae kh RHEE, whose The Multiverse Portraits imagines herself in parallel universes. The images are evocative as both self-portraits and imagined self-portraits of what one could look like. Can you describe the portraits?

Mirae kh RHEE is an interdisciplinary artist based in Berlin whose self-portrait series The Multiverse Portraits (2015-2016) was at the center of my recently published essay, “Monstrous Beauty: Unruly Bodies and Diasporic Plasticity in kate-hers RHEE’s ‘The Multiverse Portraits.’” (The artist was formerly known as kate-hers RHEE but now professionally uses the name Mirae kh RHEE.) The work is a multimedia installation that incorporates photography and drawing in its speculative representation of RHEE’s body across three imagined parallel universes: The Reality Universe, The Gangnam Universe, and The Ethnic Hardening Universe (Self-Portrait Exaggerating my Mongoloid Features). These imagined “co-existing self-contained realities” are intended to evoke before and after images of pre- and post-surgery makeovers as frequently utilized in plastic surgery advertising in Korea.

The Reality Universe is a photographic portrait of RHEE in what she describes as “unflattering lighting” and “unflattering clothing,” meant to reference the “before” images of plastic surgery transformations.

In contrast, her post-makeover portrait, The Gangnam Universe, is a heavily photoshopped rendering in which her face and body have been altered in accordance with Korean beauty standards.

Lastly, The Ethnic Hardening Universe (Self-Portrait Exaggerating my Mongoloid Features) is a direct response to what American plastic surgeons refer to as “ethnic softening,” a term used to describe cosmetic procedures performed on non-white patients. As the term implies, such procedures are intended to soften the “hardness,” which is to say the seeming immutability, of racialized facial features.

I was really captivated by how RHEE leans into and plays with the body horror of the plastic surgery monster by literally metamorphosizing her body through Photoshop and drawing. She gets us to critically reflect on how biological determinations of race continue to persist in the ways we make meaning out of the face and body (i.e. “African American nose,” “Asian eyes,” “Caucasian nose”). By surfacing these taken-for-granted racial signifiers and then also contorting them, RHEE pushes us to lean into our voyeuristic viewing practices, inviting viewers to look, stare, and feel by recruiting ethnographic techniques of photographic documentation.

As a self-described “visual anthropological presentation,” the taxonomical and taxidermic display of RHEE’s face and body across all three portraits borrows criminal portraiture conventions, showcasing RHEE in both full-body shots and headshots. Here, RHEE complicates pre- and post-surgery photography to draw out its shared aesthetic form with photographic conventions that have historically rendered racialized subjects into objects of surveillance. And so, as participatory spectators, we become enmeshed in this visual history. The Multiverse Portraits captures our attention and holds our gaze in ways that might feel unsettling. You want to look away, but you can’t. What happens in these moments of repulsion and discomfort?

These images are both realistic and manufactured, as if they are both anthropological taxonomies and imagined selves. How does the simultaneous realism and lack of realism in these images shape your reading of the artworks?

The trouble with realism is at the heart of RHEE’s work. It’s the very slipperiness of “realness” that RHEE draws out and experiments with across her self-portraits. Plastic surgery procedures and their consumers are often indicted as “fake,” “artificial,” and “excessive.” However, such critiques implicitly depend on the legitimacy and coherence of a “natural” and “real” body, which, as scholars across ethnic studies, Black studies, Native studies, disability studies, and feminist queer theory have made clear, reifies the human body as a stable, discrete entity. And so, I’m really captivated by how RHEE takes up plastic surgery as a direct mode of address whereby we are tasked with confronting our presumptions of authenticity. By getting us to think hard about what kinds of beauty we celebrate as “truthful” and condemn as “deceptive,” RHEE extends a larger critique about how transpacific projects of war racialize non-normative bodies and subjectivities as deficient and unruly, and thus in need of repair.

By appropriating ethnographic tropes and methods, RHEE is able to morph and contort her body in ways that render her self-representation unreliable. For instance, in The Ethnic Hardening Universe, we can see that she has hyberbolized certain phenotypic features such as her nose, cheekbones, and jaw, while minimizing others, most notably her eyes. In so doing, RHEE leans into the ugly artifice of not only her plasticized body, but also the dysphoria of her ethnoracial “inauthenticity” as an adopted Korean person.

As Korean adoption studies scholars like Eleana Kim, Kim Park Nelson, Tobias Hübinette, and Arissa Oh demonstrate, Korean transnational adoption began as a post-war response to not only the surplus of orphaned children, but also more specifically, mixed-race children born to American GI and UN officer fathers and unwed Korean mothers. These adoptions exploded in the mid-1980s, with an average of 8,000 children leaving Korea every year. Korean babies would prove to be a powerful transnational currency that would inaugurate not only Korean modernization by way of millions of crucial dollars in national revenue, but also secure diplomatic relations with the Western nations receiving Korea’s expendable children. Against this historical context, RHEE thus undermines the assumed veracity of her own self- representation as an adopted Korean person, unsettling any viewing desire for her full interiority. And so, while her portraits are presented as a diptych in the gallery space, her work might be more fully read as a triptych that surfaces the unlikely historical intimacies connecting the transracially adopted Korean, the plastic Korean woman, and the primitive ethnographic spectacle together.

Ultimately, I read RHEE’s playful tarrying with racialized markers of her face and body as a means to disrupt our visual field and our assumptions of what (or who) gets to count as a “real” body and who gets to count as a “real” Korean. By playing with our expectations of what a Korean body looks, sounds, acts, and feels like, RHEE ultimately sabotages the fantasies of American benevolence and Korean modernity that attempt to resignify overseas Korean adoptees as flagbearers of Korea’s vision of cosmopolitan futurity. RHEE rejects this demand for legibility, and instead maintains her artificiality and inauthenticity. She remains intentionally inscrutable; she is out of reach, and deliberately so.

Mirae kh RHEE’s work is part of a broader set of works from the Korean diaspora that you examine. Why examine these works from the diaspora, and what do you think they can help us understand about Koreanness?

Throughout my fieldwork in Korea, I’ve witnessed and experienced a real urgency from multiple state actors to consolidate a national Korean brand — in other words, a locatable and identifiable category of Koreanness. From K-Dramas to K-Pop to K-Literature to K-Food, the global explosion and circulation of Korean cultural productions since the turn of the 21st century has assembled a highly flexible imagination of Korea and Koreanness. The ubiquitous attachment of the prefix “K” to any and all Korean goods, products, and services attempts to seamlessly cohere “Korea” into a site and object that is at once immediately legible and endlessly elastic.

The recruitment of the Korean diaspora — in particular, Korean adoptees — in the making of a “Global Korea” is one such instance. However, this global branding obscures the Korean War’s ongoing effects by papering over how foundational militarized violence has been to Korea’s state-building endeavors. And so, the diasporic Korean artists whose work I study disrupt the legibility of Koreanness, thereby calling attention to the violent histories and present realities of militarized life. I argue that this disruption functions as a form of diasporic critique that ultimately refuses reconciliation in permanent war. It feels vital, then, to turn to the diaspora and diasporic cultural producers who are grappling with the violences of war, which have shaped forces of displacement, migration, and family separation. If we are to take seriously the unended status of the Korean War, then I want to know how conceptualizations of Korean beauty get trafficked through formulations and fantasies of repair, which I argue is about more than just the body as a site of aesthetic optimization.

My attention to aesthetics and visual culture invites a serious consideration of how diasporic art heightens our attention, pressing us to think with and learn from seemingly unlikely characters, fields of thought, and geographies that would otherwise not be thought of together. From Canada to Denmark to the United States, the works I assemble are necessarily transnational in scope because I am interested in how aesthetic practices in the diaspora surface the sensorial violence of ongoing war while carving out forms of intimacy and relationality — a diasporic theorization of healing — that take up repair as a collective, expansive process. At the heart of my research is a commitment to taking seriously the profound meaning and political thrust that beauty has in our social worlds, whether or not we’re entirely tuned in to its magnitude. And so, I hope that my project might offer some openings, some other options and possibilities for thinking about what beauty means to us and our lives, and why that all matters so much.