How do American child welfare and obstetric healthcare converge? Matty Lichtenstein, a recent PhD from UC Berkeley’s Department of Sociology, studies how state and professional organizations shape social and health inequalities in maternal and child welfare. Her current book project focuses on evolving conceptions of risk in social work and medicine, illustrated by a study of the intertwined development of American child and perinatal protective policies. She is working on several collaborations related to this theme, including studies of maltreatment-related fatality rates, the racialization of medical reporting of substance-exposed infants, and risk assessment in child welfare.

In another stream of research, she has written on social policy change, with a focus on educational regulation and political advocacy, and she has conducted research on culture, religion, and politics. Dr. Lichtenstein’s work has been published in American Journal of Sociology, Qualitative Methods, and Sociological Methods and Research. She is currently a postdoctoral research associate at the Watson Institute for International and Public Affairs at Brown University.

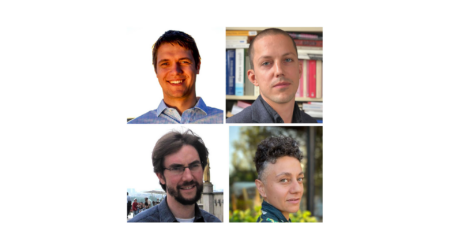

In this podcast episode, Matrix content curator Julia Sizek speaks with Lichtenstein about her research on the transformation of American child welfare — and the impact of that transformation on contemporary maternal and infant health practices.

Podcast Transcript

Woman’s Voice: The Matrix Podcast is a production of Social Science Matrix, an interdisciplinary Research Center at the University of California, Berkeley.

Julia Sizek: Hello and welcome to the Social Science Matrix Podcast. I’m Julia Sizek, your host. And today we’re talking to Matty Lichtenstein, who is a postdoctoral research associate at the Watson Institute for International and Public Affairs at Brown University.

She earned her PhD in sociology at Berkeley in summer 2021. Today, we’ll be discussing her dissertation research, which concerns the Politics of Health and Welfare Governance from the 1930s to the present.

Marty, welcome to The Matrix Podcast

Matty Lichtenstein: Thank you. Thank you for having me.

Sizek: Let’s get started by understanding the basic overview of your work on child welfare. Why were you interested in this topic of study?

Lichtenstein: Thanks for that question. I’m broadly interested in questions about social policy, health, and gender. In particular, my research has focused on family regulation, by which I mean professional or state interventions in families, and how those interventions are linked to efforts to mitigate or to inadvertently reproduce inequality.

As part of this, I’ve studied child welfare, I’ve studied educational policy. I’ve also studied gender roles and organizations. But the project that started my interest in child welfare in particular, began when I first started looking at research for my dissertation.

And I was trying to understand what the role of child welfare agencies in the United States is when it comes to interventions in substance-exposed infants. And by that I mean infants who during pregnancy their mothers used any sort of substance that medical professionals might deem harmful or child welfare professionals would deem harmful.

So when I was looking at this topic, there were two very different kinds of literatures on it. One was the literature on best practices toward this issue. So the literature on best practices tended to emphasize a lot that we need an disciplinary approach to this issue.

So if you have a case of substance-exposed infants or substance use during pregnancy, we need basically teamwork. We need medical professionals. We need drug counseling. We need social work counseling, as well as potentially we might need child welfare interventions. But it’s a multidisciplinary approach.

When I looked at the empirical research on what actually happens with such interventions, most of it, which was largely located in political science and the legal fields, tended to highlight the criminalization of these women or forced medical interventions with women who use substances during pregnancy.

However, when I looked at the actual policies– so when I moved away from the secondary literature and I started to look at the policies that focus on this issue, I saw that the policies overwhelmingly authorized child welfare. So there isn’t actually that much criminalization in the law. It’s overwhelmingly child welfare that’s the profession that tends to intervene in such cases.

And when it comes to child welfare interventions with such cases, those interventions are often linked to high levels of foster care placement of these substance-exposed infants, which the literature sees as potentially problematic for substance-exposed infants healing process.

So my question was, how did we get here? How did child welfare become authorized to do this? So, in brief, my research shows that child welfare has over the past several decades developed into a profession with considerable resources– nearly $30 billion in 2018, to focus overwhelmingly on reducing the risk of child abuse and neglect.

And one important tool of this sort of risk reduction is child welfare’s ability to coerce families into interventions through this threat of child removal. This combination of coercion and risk prevention is built on child welfare’s national infrastructure to actually carry out these interventions.

And combination of these three things is what convinced state legislators to authorize child welfare as a primary authority authorized to intervene in substance-exposed infants beginning as far back as the 1980s. But what was interesting about this was that to figure this out, I had to slowly unpack this because child welfare was not always like this.

It wasn’t always a national network of agencies. It didn’t always have this strong focus on maltreatment. Instead, I found that there were actually major transformations in American child welfare during the 20th century that brought us to this point.

Sizek: So how has the child welfare system changed over the span that you study?

Lichtenstein: Sure. So I focused my research starting after the passage of the Social Security Act because that is the big dividing line for American Child Welfare. Prior to 1935 when the Social Security Act was passed, we basically had a sort of fragmented patchwork of mostly private child welfare agencies throughout the United States.

The passage of the Social Security Act basically enabled a massive expansion of– well, I don’t know if massive, but a reasonable expansion of funding for public child welfare in particular. So state and local public child welfare. And the main shift that happened over there had to do with really thinking about what welfare meant and what it still means today.

So in general, when we think about welfare, we are referring to government support for individuals or groups. And the main distinction, especially in the 1930s, was between support as financial support– giving people money when they needed it and couldn’t get it any other way. Or some sort of services.

So that could mean something like referral to medical services, funded medical services, educational services, or it could also mean psychological counseling. And across social work in general, which was the parent discipline of child welfare.

It had that tension between how do they help people? Do they help people by getting them financial aid? Do they help people through social services? And there had been this development throughout the ’20s and ’30s toward emphasizing social services. That social workers were essentially able to provide mental health counseling, perhaps references, et cetera. Though some did focus on financial aid.

The Social Security Act made that distinction quite clear for child welfare services because the section that focuses on child welfare services emphasized that this was about services in general. And not financial aid. Financial aid was a separate part of the Social Security Act for families.

And so one of the things that the public child welfare in particular and increasingly private child welfare as well had to figure out is what does it mean to be child welfare? How do you serve children? And one of the things that I find is that there was this increasing emphasis in the ’30s and ’40s, in basically trying to develop a population that child welfare serves.

Basically trying to argue that child welfare has a specific function and that is to serve all of the various needs that children have. And that emphasis on we’re providing all of the needs of children have, not just poverty-related. In fact, they veered a little bit away from poverty-related needs, towards psychological needs, medical needs, health needs, et cetera.

Helped child welfare advocates push for more funding and more resources for child welfare. And so one of the things that happened is that public child welfare in particular grew exponentially over this period in the 1950s and 1960s.

And so the number of child welfare workers started rising dramatically. Went from 2200 in 1946 to 13,000 by 1959. Funding rose dramatically. And so you really had this huge expansion. And this leads really to one of the important things that I find which is that this led to a larger shift in child welfare and thinking about what child welfare is meant in the ’60s and ’70s.

Sizek: So I think you gave a great overview of not only the complexity of the child welfare system, but also the way that it changes over time. What people think or prioritize for children’s welfare. So what becomes the focus of the child welfare system in the ’60s and ’70s?

Lichtenstein: So one of the major findings of my dissertation, very much conflicts with the conventional narrative of child welfare history. So the classic narrative of child welfare history is that there was in the ’60s– starting in the late ’50s, and then in the particularly in the ’60s, we saw the discovery of child abuse as a social problem.

So before then, scholars argue, by the late 1950s, nobody was talking about child abuse and neglect. Nobody cared about child abuse or neglect, basically social workers and the public just did not see it as a problem. And that in the ’50s, in the research world, you start seeing more of an emphasis on child abuse.

And by the ’60s, it had become a public and political issue and you see an enormous amount of laws being passed to mandate reporting of child abuse. And this leads to basically the creation of child welfare as we know it today, which is highly and heavily focused on child abuse prevention and response.

The problem– for a while, I was following this narrative in thinking about different aspects of my research. The problem was that as I dug through more archival resources, I found that that just wasn’t the case.

So sort of the most damning piece of evidence that I found was a publicly available report that was put out by the Children’s Bureau in 1959, which stated that 49% of public child welfare in-home services related to abuse and neglect. And this was in 1959 when current scholars are saying nobody talked about abuse and neglect.

And the survey showed half of in-home services at least for public child welfare, which was the dominant provider of child welfare services at the time, related to abuse and neglect. And so I spent a few months in a sort of existential crisis of what is the meaning of my dissertation? I don’t understand. Everything is wrong.

And eventually, I figured out that not everything is wrong. A lot of what was written in this historical works about the history of child welfare were correct. There was much more of an emphasis on child abuse. There were this research on the causes of child abuse. Those laws did pass. All of that was correct.

But what it missed was this larger moment of transformation in child welfare. So as I said previously, the Social Security Act allowed child welfare to establish what they were about. And what they decided they were about was serving all of the possible comprehensive needs of children in America. And that meant everything.

So when you look at the reports and the materials that child welfare agencies and the Children’s Bureau were producing in that period from 1935 through the 1960s, there’s just basically everything in there. We’re going to focus on medical problems. We are going to focus on educational problems. We’re going to fix all of the psychological and social and physical needs of children.

Childhood abuse and neglect? Sure. That, we’re also going to fix. It’s all there. What actually happened– what I show is that it’s not so much the child welfare agencies and employees rediscover child abuse, as much as they relinquished and sometimes willingly and sometimes unwillingly any jurisdiction over most other child welfare issues, including poverty, health issues, and education, and retain jurisdiction only over child abuse and child abuse and child neglect.

And what I show is that this happened largely due to larger trends in the American welfare state, specifically welfare state retraction and increasing focus on efficiency in welfare governance in the late ’60s and 1970s, which basically demanded that child welfare focus on issues that could be easily defined and easily provided services that you could put a price on.

So foster care, adoption. This vague counseling for all of these different things, that was not something that was of interest to administrators. And this was part of also a larger process in what I call a shift from population to problem. So the Children’s Bureau could no longer be– say, hey, we serve all of the needs of the population of children. Instead, there was an increasing shift toward what is the problem you’re here to resolve?

Problems like health go to the health department. Problems like education, go to the education department. What do you focus on? Your problem is child abuse and neglect. And so that sort of– yes, there were advocates that pushed for more focus. But it was all part of this larger shift in the American welfare state that enabled this to happen.

And the other thing that I also emphasize a lot is that previous massive expansion of child welfare in response to we’re here to serve all of the needs of children. That growth of staffing, that growth of funding, also made it possible for all of these laws saying, hey, you need to report child abuse to say, well, where do you report it to? Well now you have a child welfare agency.

Now, there are thousands of child welfare workers. So you kind of have this unintended consequence that happens where all of those new child welfare workers that were supposed to solve all of children’s problems, to put maybe a little simplistically, were now there to solve one problem, which was the increasing number of reports of child abuse and neglect.

Sizek: Yeah, so let’s try to understand what ends up falling into the category of child abuse and neglect because it seems it’s both a specific problem that people are identifying and then also sort of a capacious category that ends up, as I think, as you write about how I guess it brings in these other questions about is poverty an example of child abuse and neglect. So, what is this category? How is it initially defined, and how does it transform over time?

Lichtenstein: So the early research that really tried to refine this issue and try to say, you know what does it mean to have abusive parents, was primarily in medical journals. And that was usually based on things like X-rays of children with broken bones and trying to figure out was this an accident or was this caused by who could it be caused by. And then also psychiatric evaluations of parents saying, what is wrong with parents who do this and how does this happen sort of a diagnostic model of approaching child abuse and neglect.

And so the cases that they were referring to were usually fairly severe cases of child abuse and neglect. However, the laws that were passed in the 1960s basically told professionals across the board. Originally, in the 1960s, a lot of the laws mostly addressed medical professionals, but they quickly expanded in part because medical professionals pushed back and said we can’t be the only ones mandated to report this.

And so it quickly started to expand throughout the 1960s and through the 1970s to include professionals across the board who have any sort of interaction with children, teachers, anyone in an educational setting, anyone in a medical setting. Obviously, people who work with in funeral homes, anything like that might have any sort of interaction.

Photographers eventually were basically became mandated reporters which means that they would be penalized at least formally they were supposed to be penalized if they did not report what were often very vaguely defined forms of abuse and neglect. And so essentially they were being asked to report any sort of suspicion of abuse and neglect. This varied greatly across states. Every state had different laws have different sets of mandated reporters. There’s a huge amount of variation.

And so what happens is that child welfare becomes the recipient. Child welfare agencies across the country in different counties and different states start to receive a skyrocketing number of reports. Now this does not mean that everyone is reporting every suspicion. A little bit of data we have on this a lot of mandated professionals either ignored this didn’t necessarily report it, et cetera.

But there was enough based on all of these new mandated reporting laws, enough reports pouring into child welfare that they basically had to figure out, especially because they had lost jurisdiction over so many other issues they had to figure out what do they do with all of these reports. And so as a result that forced in the 1970s, beginning in the 1970s and then increasingly in the 1980s a sort of reckoning of what does it mean. How do we define child abuse? And then more importantly, how do we figure out if what’s happening is child abuse and neglect?

And the thing that’s important to understand in this context is that out of these, hundreds of thousands and then millions of reports that started pouring in during this era. The majority of the reports were usually unsubstantiated. So, in the mid-1970s, when we started to have this data, usually around 60% of reports were unsubstantiated. The majority of reports that are substantiated are neglect reports, and those are highly correlated with poverty.

So something like from the data again, some of this data we only have for later years, but something like in terms of substantiated reports of neglect, there’s eight times the rate of substantiated reports of physical neglect among low socioeconomic status children versus middle or non-low socioeconomic status children. So what that means is that you have this very broad category of neglect, which could include everything from passively allowing your child to starve to not having child care, so leaving your child home alone for a few hours when you go out to work.

So just this huge range that varies again by state by county in some states and all of this is basically sort of evolving in the ’70s and ’80s. And so then the question becomes, if you have this huge number of reports coming in and the majority of them are not even actual abuse and neglect, and the majority of the ones that you determine as abuse, neglect it’s not even clear if it’s neglect or it’s poverty, the question then becomes, how do you create a system to prevent and treat a problem that we’re not even sure exists?

And that’s really where you start to see this focus on risk. Child welfare and medical professionals affiliated with child welfare begin to develop different tools, practical risk assessment tools, to try to determine what is the risk that A, there’s an actual case of child abuse happening or even we can’t actually say that there is any abuse and neglect happening here, but maybe it will in the future. This is a high-risk situation.

So this is the period in which they start to develop these tools in the ’70s and ’80s, and these tools have all sorts of problems that are built into them in that period.

Sizek: So let’s dig in a little bit into this emergence of the system of surveillance and the transformation of these surveillance processes into these risk assessment tools. So, can you tell us a little bit about one of the risk assessment tools that these professionals are using, just what it looks like if you’re a doctor or a social worker and you’re going into a home with this list of questions?

Lichtenstein: Sure. So, the thing to keep in mind is that the early tools in the ’70s and ’80s were often built on what was called a consensus approach to risk assessment. And so what that essentially meant is that it was built on what social workers consider risk variables. And so this was deemed very problematic by the 1990s, but they were still widely used for the first 20 or so years in which tools were spreading.

And so these tools tended to incorporate all kinds of variables having to do with the environment of the child. So not so much again we don’t necessarily have any sign that the child is harmed directly. There’s no sign on their body. There’s no necessarily sign in how they’re speaking, but we look at the environment, and we try to assess if there are risk variables there.

So that has to do with everything from the income status of the family with the health issues of parents, marital status of the mother, usually the mother, child care access could be a risk factor, as well as other issues like the stability of the home. There were risk assessment tools in the 1970s that also had factors like does the family, do the parents take this child to movies? Do they have a camera? Do they take the child fishing?

In addition to, is there dangerous wiring? Do they all sleep in the same room? Does a child have a mattress? So what you can sense from this is there’s just a huge– it’s just really hard to disentangle poverty from this. There are also sometimes sort of cultural factors.

So you’d have questions about does the parent have this as an early tool, and I think 1978, if I recall correctly, where they asked if that was approved by the predecessor to the Department of Health and Human Services and recommended it for wide use among social workers and this tool asked the question about whether the parent had wider family support in child care. But then also asked about whether they were overly dependent on their family.

So, putting aside the paradox in that that also gets at something that is cultural, not just economic, which is that often in families of color, studies have found that there’s more interdependence that there isn’t as much of an emphasis on nuclear family units and this itself could be seen as problematic in some of these risk assessment tools. And then, of course, there’s drug or alcohol use was assessed as a risk factor.

And the thing that’s also important to recognize in this is that when you look at the earlier surveys about child welfare services before this transformation to focus on child abuse, they would talk about health and family issues as issues that child welfare addressed, but they weren’t risk factors for abuse. So you’d see a survey about what a child welfare do why do they intervene in a family. And one of the reasons could be, hey, there’s some sort of health issue with a parent but that was seen as distinct.

Whereas when you look at the later studies in the 1970s and by the 1980s for sure, those same factors are no longer seen as like they intervened because of the health issue. Now it’s, is this health issue a risk factor for abuse or neglect? And so you see this sort of transformation of structural factors, structural inequalities, and health issues into risk factors. And part of what that does also is instead of trying to say, how do we help this family as a whole, you instead have a sort of a how do we assess– the assumption is we’re trying to see if the parent is harming the child.

So, there’s an approach in which a parent and child are seen as distinct units. And the question is, are they in some sort of conflict? And part of the thing that I think is most interesting about this is that this is a relatively rare problem in which there is sort of this intentional effort of the parent to harm the child it certainly happens. But it’s relatively rare and you see it in the data that it’s relatively rare.

And so the framing is basically, like I said before, trying to find a problem that isn’t very common. And so instead, we kind of have to take things that are more common, like poverty and other issues, and try to see, well, can we link it to a risk of this problem of child abuse or neglect happening down the line.

Sizek: Yeah, I think another thing that you really bring up is the way that these systems are interrelated to each other that, for example, the medical system is implicated in child welfare or that the general welfare system becomes part or entangled with child welfare. Can you speak a little bit about how this balance between these multiple systems that have to do with children as people are interacting and how they’ve been changing over time?

Lichtenstein: Sure. So, there’s always been this somewhat messy relationship between these different systems. So yes, first of all, the questions of things like healthcare access, child care access, income inequality, racial discrimination, all of these different issues and then, of course, like deeply gendered issues like the fact that was most frequently the woman who was taking care of the child in a lot of these cases. All of these different issues become interrelated with child welfare.

And so one of the more you– see this going back quite far. And you see this going back in particular before this transformation already you see this issue. And so one of the ways this happens is that, as I mentioned before, child welfare develops in the ’40s and ’50s and they say, hey, we’re not in charge of financial relief. That’s a different department. That’s the welfare department.

The one that administers what was then the ADC and then later became the AFDC and then later became TANF. That’s the department that’s in charge of financial relief. We’re just here to help families become healthier, and happier, and more functional.

And that was technically true to some degree. But what happened was that there was also this almost like pride with which advocates for child welfare at that period in that period would say, we don’t actually serve poor children very much. And so there was a very widely cited report in 1959. It was cited in the very, very influential 1962 public welfare amendments. It was part of the hearings, and it was put together by a council of who’s who of child welfare leaders.

And they said, you know, hey, only 9% of children that receive child welfare services also receive ADC. This is very misleading because to qualify for ADC at that time, you had to meet a series of requirements that many poor families did not meet. And in particular, there was a lot of racial discrimination in ADC, and so that this did not actually mean that child welfare services only dealt with middle-class and upper-class children.

But it was interesting to see how these advocates tried to present themselves, try to present the profession as being about something other than poverty, as being a profession that focuses on these complex psychological family problems. And so this sort of framing, though, also enabled child welfare to say, let’s look at all these problems and frame them as though basically an individual issue a problem with an individual family with an individual parent. This isn’t related to larger structural issues like poverty or race.

And so that enabled child welfare to develop as a profession in this way. And so it’s not like particularly shocking that when you have this increasing shift to child maltreatment, there’s basically sort of a shift toward we’re going to keep up this focus on psychologically approaching these larger problems of child maltreatment, and we’re going to keep delinking it from poverty. This isn’t necessarily intentional.

Many social workers no doubt walked into a family and immediately realized the problem was poverty, yet had no access to resources to directly aid families who needed assistance with finances. Yet when you look at reports from the child welfare reports from the ’70s and ’80s, whether this is broader structural issues, whether they’re social worker bias or not, the fact is that what you see is a sort of transformation of the structural problems into individual psychological problems of the parents who essentially choose quote-unquote “To neglect or abuse their children.”

Sizek: So can you walk us through maybe a case or two of what the, I guess, what would the implications look like for an individual family? What are the forms of surveillance that they might be subjected to or the ramifications of these abuse policies for an individual family like, I guess, over the course of a year?

Lichtenstein: Yeah. So, I should be very clear that I am not an ethnographer. So, I’m actually the person not well equipped to answer the question based on my own data, but there is fantastic work out there that I use to inform my policy level research. And I also did– part of my research has focused on– a big chunk of my data comes from the Child Welfare Journal, which I looked at historically over the years and there there’s a lot of case studies. And so, I was able to draw in some of this into my research.

So I would say that part of what happens is that there’s a report. That’s always the first step. Very few cases are self-reported. Most cases are reported. And this is also a shift, by the way.

You see, in articles by child welfare workers in the ’50s and ’60s, they describe people calling them for help, saying, hey, my wife just was put into a mental asylum, and I can’t take care of my kids and work, and what do I do? And literally, they describe this sort of emergency cases where they would put the child short term in foster care or something like that in response. And you see that decreasing when there’s a shift to maltreatment.

So you have a report. Over time, those reports increasingly come from professionals. In the 2018 report from the Children’s Bureau, it was something like 2/3 of her reports come from professionals. And this report leads to first some sort of assessment. It’s not necessarily called an investigation at first. This varies by state.

But child welfare will at least assess whether it’s worth contacting and investigating the family. And then that’s the next step if they don’t shut it down immediately because sometimes they do. Some of the reports won’t allege anything that’s worth investigating, and so they won’t investigate. And so then there’s an investigation if they assume– if they assess that there is some reason to investigate.

And that investigation generally involves a visit to the family. And this is where things, again, my research is historical. It’s from 1935 to 2000, which is a very long time, and then since then, I’ve been reading, a lot of research that’s been done on changes in child welfare since then. And so this has changed in a variety of ways.

And the other thing that’s important to know is that the response varies highly depending on what state you’re in. So Frank Edwards is a colleague of mine who has done a fantastic piece on how the amount of resources that states invest in general in welfare support are highly correlated with the kind of responses that they have to cases of child maltreatment.

And so he basically found that states that do not invest, in general, in social workers in financial support are also more likely to put children who are removed from families into very more severe settings, so institutional settings or group homes, which are considered more severe than foster care or other sort of supportive services. So there’s a lot of variation by state in what actually happens.

But in that first step where the child welfare shows up at your door, a different colleague of mine, Kelly Fong, has done published some very interesting research on what I think is a really important point that links to what I spoke about earlier. Child welfare shows up, and they ask to come into the home, and they ask can I speak to your children. And in some cases, that speaking could involve physical examination and it could involve all sorts of invasive questions.

Parents are not necessarily obligated to respond or to comply. However, one of the things that Kelly Fong found is that they will comply even if they don’t have to, even if there’s no legal obligation to because they know that their child could be taken away. And they know that because child welfare is a civil system, there’s just so little transparency and so much discretion that there’s really, once you go down there, you can just be in this endless black hole.

So your child can get taken away, and you may never get that child back. And it’s not very clear why you’re never getting that child back. Generally, child welfare cases, it’s not up to the social worker. It goes to a court. But that court proceedings are generally sealed to protect the privacy of the family.

But that also means we don’t really know what are the standards or, how and why these removals are determined, or how other interventions are determined. But just that fear of losing the child means that parents will comply at a very high level in many cases. And this focus on child removal is something that is something that is difficult to pin down and say, well, do they come in and say, you’re going to lose your kid?

No, but parents know this. And so it leads to a certain set of behaviors.

Sizek: I actually had another question related to this system, which you mentioned has it’s very hard for families to keep track of their own children within the system or for researchers like you to also try to keep track of people. How did the challenges of studying the child welfare system shape your study and how you approached your research?

Lichtenstein: Yeah, so it was extremely challenging. There’s no here’s a beautiful data set. There are data sets, but first of all most of them trying to do historical child welfare is incredibly difficult. Most data is from literally the past 20 to 30 years. Some data has never been systematically collected.

So, for example, the Children’s Bureau puts out reports on child abuse and neglect and reports and treatment, and I’m sorry responses, and so on. They’ve been putting those reports out technically since 1990, but the data is highly incomplete until the early 2000. So you’re literally talking like there isn’t any data earlier in a consistent way.

And because of this shift, because of the Children’s Bureau and child welfare in general lost jurisdiction over some of these other issues, there’s also this huge shift in how data around child welfare was produced. And so just finding reports about the published reports, publicly available published reports on child welfare was quite difficult. There isn’t a lot of institutional memory because there has been this enormous change.

And so I spent the first couple of years just sort of scrambling to try to figure out where do I find this data, where is the historical data on child welfare. Most people who study child welfare tend to focus on one state, so they find that one archive or having something to do with child welfare, and that’s what they focus on. Or there’s an excellent ethnographies where they focus on one site.

Trying to do the sort of broader study of American child welfare policy going back this far is really, really challenging because the data is just a mess, to put it bluntly. So the way I sort of went about it was I triangulated multiple data sources. So the first thing I did was get my hands on a lot of that published data from the Children’s Bureau starting already in the 1940s. And that, there’s just a lot of data.

Most of it is not. I had to spend a lot of time on transferring that into usable spreadsheets so I could figure out what the numbers were and what the trends were but there were a lot of just little booklets that they put out with a lot of data from that. So, and then supplementing that with a lot of archival research, though, again, that was harder than it should have been, I think.

The second thing I did was that you have this journal called the Child Welfare Journal, and that’s been it’s still around, and it’s been around since 1921 so it’s 100 years old now. And so it’s been a pretty consistent reflection of what researchers and practitioners in child welfare have been doing for the past 100 years. It’s not a good reflection of clients. It’s not a good reflection of families receiving treatment. That’s very rare to see that.

But it does give you a sense of the profession, and that helped me a lot with this angle of this is a story of professionalization of child welfare of this transformation of child welfare from a tiny little subfield of social work into an independent profession that’s trying to say, this is what we do. So, that was the second major source. And to analyze that, I co-developed with my colleague, Zawadi Rucks-Ahidiana, I co-developed a method called Contextual Text Coding, and that helped me analyze these journals in a systematic way because we’re looking at again 50 years worth of journals, so a lot of data.

Finally, I did a lot of historical legal research, just trying to figure out this is policy, so how did all these policies change? What did they mean? I looked at State level laws. I looked at national laws. And then, I supplemented all of this with a little bit just about 15 interviews. This is a small number because these were purposive interviews, so I specifically chose people who could just explain some of these gaps, like what is going on in this policy what actually happened here. Why did they change the way they ran the surveys in the ’80s and the ’90s? How did they decide to add all of these terms?

So these were people I spoke to who had been in child welfare in the ’60s, ’70s, ’80s, ’90s who were able to give me a perspective that I couldn’t have gotten otherwise. So, putting all of that together gave me way too much data, but it did give me a sense of these larger transformations of American child welfare.

Sizek: One of the things that you mentioned is that you worked across a couple of different states and that this is often really challenging for researchers to do. So, what are some of the key differences or distinctions in child welfare policy across different states?

Lichtenstein: That is sort of the fundamental issue in American child welfare is that there’s a huge amount of variation across states. So again, starting by, I would say, by the ’80s, one thing that was incontrovertible is that child welfare focused on child maltreatment primarily. So if you look up any department of Children and Family department, every state has a different name.

And then there are some states a small number of states that are not– there isn’t even a state centralized source. So the state like California actually it’s County run. So essentially, we have 58 different child welfare systems in California. They’re heavily influenced perhaps by state policies, but it’s fundamentally County run. And that most states, however, are state-run so the policies are set on the state level.

These different state policies are influenced by federal funding. So the government will say things like if you want our money for child welfare, then you need to define child abuse in a certain way or set up certain policies. But there aren’t really mandates in that sense. So it’s really highly fragmented. What happens in a case just highly varies.

So, what this means is twofold. First, as I mentioned before, there’s been research that shows that different levels of funding and welfare support shape responses enormously. But the other thing is that there’s just really different approaches to different issues because what abuse or neglect even means can vary by state, and how much reporting is required or who’s required to report varies by state.

And then things like how to respond to things like if a substance-exposed infant is reported to child welfare, what happens varies enormously by state. So you have in California, you’ll have different approaches that could range from child removal, which happens significant amount of time, to trying to send the mother to treatment services.

In a state like Wisconsin, they have civil commitment programs, which means that essentially the state has the right to take a woman who has been reported as using some sort of forbidden substance like drugs or alcohol during pregnancy, particularly drugs actually is the main focus and essentially imprison her in any institution other than a jail. So it could be in a drug treatment facility or something like that. And basically, the woman cannot leave.

You have very different responses to the same issues depending on the state.

Sizek: Wow. And just to return to, I guess, this what you brought up the question of substance abuse or, I guess, infants who have been exposed to substances. What are the approaches that different states take to this issue and how is it run through the civil rather than through criminal processes?

Lichtenstein: Yes. So the issue of substance-exposed infants, I think, is particularly important because it builds on what I spoke about before, which is this increasing focus on risk. As I mentioned before, some of those earliest risk assessment tools were developed by medical professionals or medical researchers as well as child welfare professionals, and some of these early tools were deeply gendered.

One of very influential tool that was developed in the 1970s, and there were sort of repeated iterations of it, essentially it was developed by assessing mothers– assessing women during pregnancy and during the childbirth and postpartum period and surveilling them to see how they treated their child. One of the telling findings of this is that the authors argued that 25% of their study population were at risk, as they put it, for what they called abnormal behavior.

And a lot of this was highly tautological. It basically was how does an abusive mother behave. Here is a list of behaviors that abusive mothers display. And how they define abuse was never clear. There were all sorts of methodological problems with these early tools.

And so this is how they behave. Well, how many of these behaviors match how a mother is behaving in the labor room and in the recovery room? Now anyone who’s seen or interacted or been a woman in a labor room or in a recovery room that is not your best moment. You know, that is a highly stressful time physically and emotionally and otherwise. And so using that as a way to assess risk is altogether sort of loaded with all sorts of interesting problems and questions.

So there was just this highly– this is not this wasn’t just one study. There were multiple tools and studies that focused on pregnancy as the time in which we try to figure out if this mother will later put her child at risk in some way. So it was sort of was conceptualized as a site of risk pregnancy is already a site of risk.

In the 1980s, you have an increasing number of reports coming into child welfare of substance use during pregnancy, whether drug use or alcohol use but particularly drug use. And a lot of this was highly racialized in terms of how it was conceptualized. So there was sort of there was a lot of media coverage of pregnant women using drugs during pregnancy and a lot of the images that were or the examples that were provided in these media reports were generally of African-American women.

So with this in mind, the emphasis at the same time simultaneously in child welfare on risk reduction on trying to figure out is this child at risk? Is this parent a risk to her child helped frame substance-exposed infants as a paradigmatic case of a child at risk for future harm. So it’s not just is the child being directly harmed right now.

As part of my research, I compared discourses in medical journals about substance use during pregnancy to social worker discourses and there was a very distinct difference between them. Medical journals tended to focus on is there some sort of direct physical harm that is caused to the child as a result of substance use during pregnancy. Social worker articles tended to focus on is the use of substances during pregnancy correlated with long term harm to the child.

So will a mother who uses some sort of drug or alcohol during pregnancy end up neglecting and abusing her child in some way? So methodologically, this is just a very complex thing to evaluate. But part of the thing again this is a multi-system process. And so part of what happened is that there was this during this period the politicization of pregnancy, the politicization of drug use during the 1980s meant that this problem received a lot of media coverage.

And what that means is that state legislators felt they had to do something basically. They had to respond in some way. And their options were basically to say, well, we can mandate medical intervention in such cases. We can criminalize these women for harming their children and mandate essentially law enforcement interventions. Or we can mandate civil interventions through child welfare.

The current scholarship on this period and really on this issue tends to focus a lot on criminalization on how pregnant women are thrown into jail and how women are jailed or prosecuted for these kinds of uses. And then there’s also a lot of conflation of they’ll talk about child welfare interventions. They’ll talk about medical interventions but make it all part of this larger criminalization and policing of pregnant women.

And there’s a lot to be said for that framework, but I think it’s actually really important to distinguish between those two things for one because criminalization is actually relatively rare. There’s only been generally of the cases that I’ve been able to find, there’s a relatively small number compared to the thousands of women who are reported in each state to child welfare every year. That is by far the predominant response is child welfare reporting.

And so when I went– historically, I looked at two states, California and Wisconsin, and I tried to figure out why does this relatively liberal and relatively conservative state again this was in the ’80s and ’90s, so not quite as polarized as they are today, but still at the time it was Republican controlled state legislature in Wisconsin and a Democrat controlled state legislature in California– why did they both choose to give child welfare predominant authority over interventions and substance exposed infants?

And one of the things that I showed is that criminalization was presented as essentially unhelpful and counterproductive. There was a lot of pushback against it from everyone, pretty much every professional pretty much pushed back. The police were not too excited to get involved in most cases. Sometimes they were, but very often they were not.

There were some individual prosecutors but as a profession. It wasn’t like give us something else to do. In terms of medical interventions, there was a lot of enthusiasm. In particular, in the California case, I found the law that mandates reporting to child welfare started off as mandating medical intervention.

So if a case came up in a hospital where a woman gave birth and it became clear or was pregnant it became clear, well, actually California had to give birth so if a woman gave birth and the child was in some way had been either affected– affected is very loosely defined– so just the woman used some sort of substance during pregnancy, then the course of action prescribed in the original bill was to involve public health nurses.

And this garnered a lot of enthusiasm. All these different organizations, prosecutors offices, medical associations, all rode into the state legislature and said, this is great. Medical interventions, this is the way to go, these comprehensive interventions. You can also work with social services this is wonderful. They kind of took that enthusiasm and that set the ball rolling for pushing the bill through.

And then in the process, they slowly stripped the public health nurses from the bill in part because public health nurses themselves said we don’t have the infrastructure to respond to this. But then also there were several different letters that I found that said they don’t have the coercive power that child welfare has to do anything about this. Like yeah, sure, we can tell public health nurses to go, but will they get the woman to stop using drugs? What if she doesn’t want to?

Child welfare, on the other hand, they have this cudgel. They can take your child away. And that’s largely the message that they gave which reflected to some degree, some of the messages I was seeing in child welfare journals at the same time about this issue. And this was convincing. The state legislators stripped public health nurses from their primary role and instead made the California law as it still stands today.

If you have a case of a child born and during pregnancy the woman used some sort of substance that is deemed as harmful to the child, you report it to child welfare. So this started off on the state level and by now it’s actually again it’s not law in the sense of mandating but it’s law in the sense that the federal law basically says if you want this funding then you better have reporting of substance exposed infants to child welfare.

And so you kind of have this shift and a lot of that has to do and the way I sort of interpret it is that a lot of this has to do with essentially a consensus that we need a way to appeal to a risk prevention framing. Again, a lot of these children are not necessarily harmed. It’s not always clear that the child is harmed. The child doesn’t have to be verifiably harmed by substance use during pregnancy.

There’s an assumption that if the woman used some sort of substance during pregnancy, the child is definitely going to be harmed. It’s actually incredibly messy, the data. If you try to find an answer to that, it’s a mess. Some substances immediately cause harm, some don’t. Some are correlated with certain outcomes that are really hard to disentangle from other factors.

So it’s a really messy question of whether a substance causes harm. And that doesn’t matter for the purpose of the law. The point of the law is if the woman ingested some sort of substance, she put her child at risk of harm. And the state legislatures wanted to find a way to say, hey, who can help approach this as a risk problem? Who can say– and they use this language of risk in the actual legislative materials, how do we essentially manage and mitigate this risk?

Child welfare, A, has this risk prevention framing and also is supposed to be dedicated to protecting children, so they are sort of the perfect response. And what’s interesting about this is that child welfare increasingly across states becomes the primary authority for intervening in such cases even as simultaneously the professional consensus increasingly converges on the idea that we need a multidisciplinary response to the issue of substance exposed infants.

So if you read anything, including from the federal government, the reports that are put out on this issue of substance exposed infants the consensus is we need doctors and social workers and financial aid and perhaps even law enforcement all, everyone needs to work together to deal with this issue of substance exposed infants. But in practice, the state laws overwhelmingly favor child welfare interventions and child welfare is mandated to mitigate risk of child abuse and neglect. That’s their mandate across the board.

They’re not there to provide a multidisciplinary approach. They can and sometimes they do. It varies greatly by state, but that’s not their primary mandate. And so that’s the framing that results. And there are very concrete consequences to having child welfare as the primary authority intervening in such cases.

Sizek: Given that child welfare is such a complex problem that is solved by this one agency or by child welfare agencies in general, what does this matter for people thinking about child welfare issues today or for thinking about child welfare policy today?

Lichtenstein: So the consequences for the issue of substance exposed infants, in particular, having child welfare be the primary authority to intervene. So just to recap some of the issues I’ve discussed. Essentially, it has several problematic consequences.

First, as I’ve explained, child welfare is just underequipped for multidimensional problems. In some states, they might have more access to other resources and in other states. Essentially, the only thing they could really do is child removal or interventions that are often quite disruptive to the family. So that’s first of all that it conflicts. Having child welfare in charge conflicts with the multidisciplinary approach that’s favored by most professionals.

The second is that child welfare is associated with an enormous amount of trauma, especially for families that are low income and for families of color in the United States. 50% of African-American children in the United States today have experienced a child welfare investigation. That’s one out of two– that’s half of African-Americans that’s just crazy. That’s just huge numbers of children that are experiencing these kinds of investigations.

Perhaps some of these investigations are very minimal. Some of them are not going to be so minimal. So what we have is just potentially and sometimes just very traumatic family surveillance and separation that’s intrinsically linked to child welfare because no matter how helpful or well-meaning a child welfare worker might be, ultimately, child welfare has the authority to take your child away possibly forever. Even if they do that quite rarely, it can still be something that is laden with fear and anxiety for families.

And one of the primary issues that I’ve mentioned before, is that you have these lower standards of evidence that are applied in child welfare proceedings. And so that makes it particularly problematic to have child welfare involved in cases of substance-exposed infants especially because at least in the limited data that we have for example for California a significant percentage of these infants are taken away from their mothers and that’s often not evidence-based. Taking a newborn away from their child from their mother is not necessarily an evidence-based approach to dealing with substance use issues.

But that makes sense because again child welfare is not equipped is not framed. The paradigm of child welfare is not necessarily to approach the best interests of the family as a whole. The paradigm of child welfare is to reduce and mitigate risk of future child abuse and neglect.

The other part of your question I think was to ask about whether there has been shifts in child welfare over time like how this has changed. Over time, there have been significant shifts. My research largely ends approximately in 2000. In the first couple of decades of the 21st century, there has been a concerted effort by child welfare agencies on every level to try to counter some of the intense racialization and income inequality that is reproduced by the child welfare system.

And so we’ve seen a dramatic decline in child removals. So for example in New York City in 1995, there were 50,000 children in foster care. In 2019, there were 8,000 children in foster care. That is a dramatic decline. However, I think something that’s important to know is that even though there were 8,000 children, there’s still been an enormous amount of children investigated.

In New York City, you have, in 2019, 44,000 families or cases essentially in preventative services. So you still have a lot of child welfare involvement. And what that means for families is not really clear to us yet. And the second major shift is that there’s been an intensification. So it’s not really a shift, it’s more like a continuation of what I described. There’s been an intensification of a focus on risk assessment.

So what this means is, again you have this increasing development and to some quite sophisticated risk assessment tools not just the consensus tools, but you have development of actuarial tools. You have the development of algorithmic tools that use computational methods to assess risk. And there’s a lot of critiques of some of these tools and there’s a lot of just controversy over these tools.

But the main issue is the question of do these tools funnel multiple problems, many of them poverty related, into child welfare? And even if racial disproportionality in some states has declined, it continues. We still have a lot of racial disproportionality in child welfare. And income inequality continues and we don’t have enough data on that to fully assess it.

And so we continue to have significant questions and significant issues with child welfare today even as it has changed in this new century.

Sizek: I think on that note, one of the things that I really appreciate about your treatment of this topic is just the way that you approach this enormous complexity and find the ways that child welfare, even though it’s been put under child welfare agencies, has just been made into a small or I guess a multidisciplinary complex problem into one kind of solution and that solution is child welfare.

So I just wanted to say thank you so much for your important research and thank you for being on the podcast.

Lichtenstein: Thank you. This was a wonderful opportunity.

Woman’s Voice: Thank you for listening. To learn more about Social Science Matrix, please visit matrix.berkeley.edu.

Listen to the full podcast above, or listen and subscribe on Apple Podcasts. For more Matrix Podcasts, including interviews and recordings of past events, visit this page.