A recent radio ad sponsored by National Nurses United, the largest union of registered nurses in the U.S., presents a conversation between a patient seeking medical care and a “digital diagnostician”.

“We have something better than nurses—algorithms!” the digital specialist says.

“Sounds like a disease,” says the patient.

“Algorithms are simple mathematical formulas that nobody understands,” the diagnostician explains. “They tell us what disease you should have based on what other patients have had.”

“OK, that makes no sense, I’m not other patients, I’m me!”

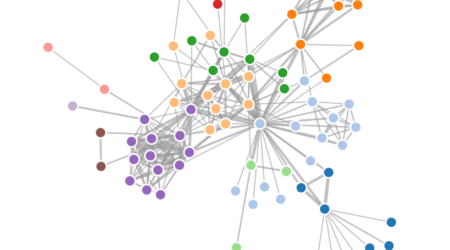

The backlash implied in this ad is just one example of how algorithms—the chains of logic through which computers make calculations—are finding their way into the broader culture, whether through politics, media, science, or everyday life. To explore the implications of algorithms’ creeping presence into modern society, UC Berkeley Social Science Matrix sponsored a seminar entitled “Algorithms as Computation and Culture,” which brought together computer scientists, social scientists, and humanities scholars.

“Algorithms and ways of analyzing them form the core of what computer science majors study,” explains Jenna Burrell, Associate Professor in UC Berkeley’s School of Information. “However, there is a growing interest coming from other fields in the ‘politics of algorithms,’ recognizing that they are consequential to society as a whole, and raise issues of discrimination and inequality, information access, and the shaping of public discourse. There are algorithms that do automated credit application analysis, decision-support systems for medical diagnosis, and others—like Google Search and Twitter Trends—that manage information search and trend identification, determining what is brought to our attention and what isn’t.”

The Matrix seminar is examining the far-reaching implications of these new technologies by bringing together perspectives from across disciplines. “The purpose is to explore ways of talking and thinking about ‘algorithms’ that are not defined solely by one disciplinary approach, though we also want to study them very concretely, looking at particular examples,” explains Burrell, who is leading the seminar. “The word ‘algorithm’ is starting to bubble up in public debate and in the media as well. We want to explore algorithms from many different angles.”

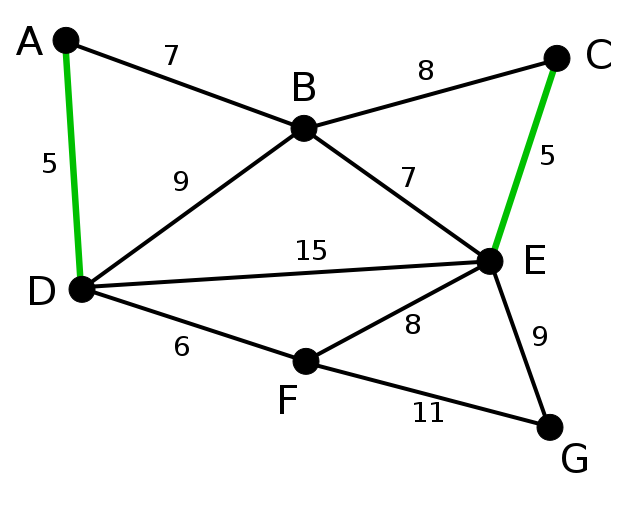

For the unfamiliar, algorithms are the “if-then” procedures for calculations that computers follow as they process information; they are constantly running behind the scenes in digital technologies. Practical examples include algorithms that run digital alarm clocks (“if ‘time’ is 3:00, then ring”), or digital radio stations that stream music based on your past preferences (“if prior choice was Bach, then play Beethoven, not Rolling Stones”). Algorithms are used in software like Facebook to determine which posts are shown on your news feed, and to determine which ads you are shown based on your past online behavior, as well as your location, age, gender, political preference, and other dimensions.

Algorithms shape opportunities and mitigate dangers. But we don’t yet have a very good handle on their ramifications.

Because algorithms are at the heart of artificial intelligence and automation, they are becoming more widely known (and controversial) as computers are increasingly employed for decision-making, particularly in roles that have previously been restricted to the domain of human beings. Hollywood producers have drawn jeers for adopting algorithms to determine whether a song or movie will be a hit. A Swedish artist raised eyebrows by creating an algorithm to determine what art pieces he should create, based on variables such as available gallery space and the past preferences of curators. And just as industrial workers in the past saw their assembly line jobs replaced by robots, attorneys and even (gasp!) journalists are seeing that much of what they do is largely replaceable by a few lines of code.

Beyond the issues of automation, questions of transparency are arising as the information we receive is shaped by computer code that is invisible to the public. “There are certain consequential, everyday algorithms for which we just don’t have access to the real code,” says Burrell. “We have just a descriptive understanding. For example the algorithm for determining Twitter trends, or the EdgeRank algorithm for prioritizing your Facebook news feed.”

The Matrix seminar—a follow-up to a past seminar on data inquiry—convened faculty and students from Berkeley’s School of Information, as well as from anthropology, history, art practice, neuroscience, law, rhetoric, sociology, and other fields. Sessions were alternatively led by social scientists, humanists, and computer scientists; unlike in traditional seminars that rely on assigned readings, participants engaged directly with algorithms to better understand how they operate.

“Though very much hidden from view, algorithms are part of our everyday lives,” Burrell says. “This is true whether you are directly using a computer and the Internet incessantly or not. For example, if your credit card information is hacked, algorithms will (ideally) dynamically identify this fraud. Algorithms shape opportunities and mitigate dangers. But because they are often quite complex and require specialist knowledge to comprehend, and because many of the most significant algorithms running in the world are kept opaque by commercial interests, we don’t yet have a very good handle on their ramifications. As social scientists and humanities scholars, we are well positioned to think about these ramifications creatively and broadly.”