Heba Alnajada is a Ph.D. Candidate in Architecture History at the University of California, Berkeley, and a 2021-2022 ACLS/Mellon Fellow. Her research focuses on architecture and urban history, with particular interests in the connections between the built environment, law, migrants and refugees, and the history of Arab and Islamic cities.

Her dissertation project situates the Syrian refugee crisis within an architectural and socio-legal history that spans from the late Ottoman period to present-day Jordan. Heba’s research builds on ten years of professional experience in architectural NGOs and urban development projects in Yemen, Libya, Jordan, and the Occupied Palestinian Territories.

Social Science Matrix content curator Julia Sizek interviewed Alnajada about her research, using images from her dissertation. (Follow Alnajada on Twitter at https://twitter.com/AlnajadaHeba.)

Figure 1: The image of the refugee camp dominates most representations of contemporary refugees, particularly Arab and Muslim refugees. World Bank image of Za’atari Refugee Camp, the world’s largest United Nations (UN) camp for Syrian refugees, buffeted in Jordan’s borderlands with Syria. Source: World Bank

Q: This image above (Figure 1), depicting refugees at a refugee camp, might seem familiar to our readers. In your research, you consider the history of the refugee camp as one of the predominant modes of understanding contemporary refugee life. How does this image reflect the history that is often told about refugee camps?

The image of the refugee camp dominates the public imagination of refugees. We see such images next to news headlines and on Facebook and Instagram feeds, with hashtags for humanitarian crises and links for donations. In such accounts, Arab and Muslim refugees are racialized, typically portrayed as flooding into European shores, or as security threats to be contained in camps. Surprisingly, such tropes appear not only in journalistic accounts, but also in academic literature. Journalists, practitioners, and policymakers often claim that refugees and western humanitarianism have a coeval history.This is especially true for Arab and Muslim refugees.

Engaging with such tropes is reductive and leads to an erasure of rich and diverse histories of refugees in various Arab and Muslim countries. After all, migration is not a new phenomenon.

In my Ph.D. dissertation, I counter the orientalist prism and ahistorical bias of such representations by situating the contemporary Syrian refugee crisis within a history that spans from late Ottoman times to the present. I look at the case of Jordan, one of the largest host-states for Palestinian and Syrian refugees in the world. By moving across geographies and historical periods, I try to underscore various forms and norms of refugee shelter. Which, I think, challenges the monolithic narrative of the refugee camp and the singular architecture of the UN camp.

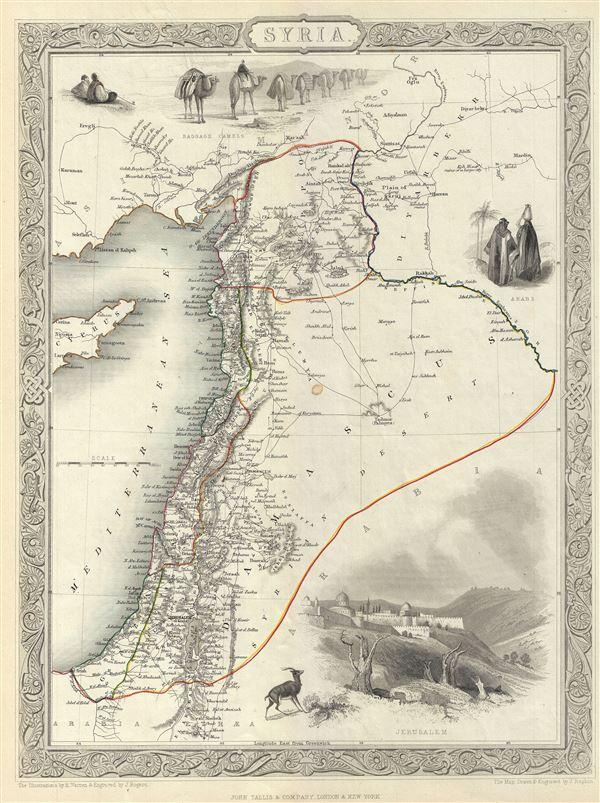

Figure 2: 1851 Map of Syria map showing the southern Eyalets and Sanjaks of Ottoman Syria — Damascus, Jerusalem, Tripoli, Beirut, Acre, Gaza, Salt, and Ma’an among others. Ottoman Syria encompassed present-day Syria, Lebanon, Palestine, and Jordan. (Map from the Illustrated Atlas, and Modern History of the World, Geographical, Political, Commercial, and Statistical: Index Gazetteer of the World. London: John Tallis and Co., 1851.)

Q: While much of your research has to do with contemporary issues, you also go back historically in your analysis of the Ottoman period of Syria, which existed prior to the splitting of the Ottoman Empire after World War I. How does the Ottoman period help us understand contemporary refugee issues?

When I began my PhD, I applied to work on the Syrian refugee crisis and contemporary urban life. But in the course of my fieldwork, clues from the present directed my attention toward Palestinian refugee camps, and then all the way back into the Ottoman Empire. I realized that to understand how most Syrian refugees in Jordan have come to find housing and employment, one needs to look at their relations with earlier groups of refugees.

In fact, less than 20 percent of the total number of Syrian refugees in Jordan live in UN camps. The rest — more than 80 percent — live outside of western humanitarian aid, among multiethnic communities that are largely migrants and refugees themselves: Palestinians, Iraqis, Egyptians, Sudanese, and Circassians and Chechens (who are the descendants of Ottoman Caucasus refugees).

In my research, I attempt to recover the thread connecting late 19th century Ottoman refugees, Palestinian survivors of 1948, and contemporary Syrian refugees. Each chapter of my dissertation serves as a reminder of an episode in an ever-evolving history of migration and the remains of earlier migrations.

Don’t get me wrong, this is not a romantic portrayal of Ottoman history. On the contrary, it is rich with accounts of contestation, ethnic/racial tension, and coexistence. I also show the persistence of Arabo-Islamic traditions of sanctuary amid the growing role of international humanitarian protection. And, in contrast to the cliché tropes of a violent and sectarian Middle East, I think that refugee settlements in this region are at once a manifestation of historical crises and the remains of alternative projects of refugee aid, solidarity, and multiethnic coexistence.

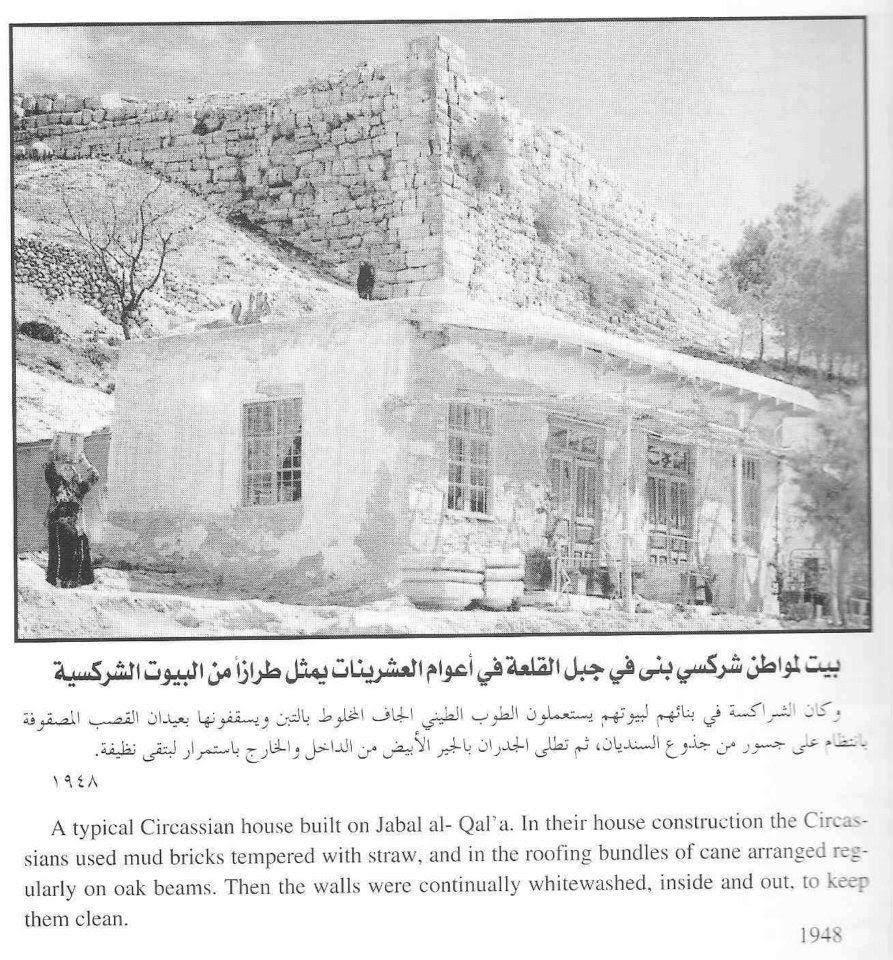

Figure 3: A typical Circassian House in Amman, 1920s. Following the Russo-Ottoman War of 1877-78, the Ottoman state received about a million North Caucasian Muslim refugees fleeing Tsarist Russian expansion. As part of the efforts to open up new areas for agricultural development, the Ottoman government resettled Caucasus refugees, primarily Circassians and Chechens, in the southern ‘frontier’ of Amman, then part of Ottoman Syria, Caucasus refugees. Source: History of Jordan (www.jordanhistory.com)

Q: You also study Circassian refugees, who came to Syria in the late 1800s. Who were Circassian refugees, and how are they relevant for understanding contemporary Palestinian refugee camps in Amman?

Yes, who were Circassian refugees? That’s a question I often get asked, especially in the American academy, but certainly not in Arab universities. Circassians are Muslim refugees from the North Caucasus, a region between the Caspian Sea and the Black Sea. After the Russo-Ottoman War of 1877-78, the Ottoman state resettled about a million North Caucasus refugees fleeing Tsarist Russian expansion across the Empire’s southern region. Caucasus refugees, primarily Circassians and Chechens, were granted Ottoman subjecthood. In Amman, then a scarcely inhabited area (today, a capital city with over four million inhabitants), the Ottoman government gave state land as shelter to each refugee household, giving some eight hectares to large families. In addition, refugees were allowed to sell and transfer usufruct rights of these lands after twenty years of cultivation. It’s fascinating to see how Ottomans had a totally different view of refugees, not as temporary asylum seekers to be contained in camps, but as permanent and mobile subjects.

After World War I and the eventual dissolution of the Ottoman Empire in 1922, Britain and France divided Ottoman Syria into four states. (Syria and Lebanon became French protectorates, while Palestine and Transjordan became British protectorates; contrary to colonies, protectorates are not directly possessed but governed by local rulers.) Britain installed the Hashemite monarchy to rule Transjordan. Amman was chosen as the capital city. As a result, lands owned by Circassian and Chechen refugees began increasing in value. Many members of the Circassian community became wealthy and influential land-owning families in Amman.

Then, in 1947, the United Nations divided Palestine. In 1948, Israel established itself over more than three-quarters of Palestinian lands. Most Palestinian refugees sought refuge in Amman since it was less than 120 miles away. Many working-class and peasant Palestinians settled in camps established by the UN Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA), the UN agency solely dedicated to the relief of Palestinian refugees. Others built their own camps on squatted lands near the center of the city. Most squatted lands were (and are still) owned by the descendants of Circassian and Chechen refugees. These camps remain unrecognized by UNRWA and are deemed “squatter settlements” by the Jordanian government. As such, property (land and houses) remains a site of intense contestation and legal disputes. Legally contested refugee camps are put into a catch-22 situation: in order to rent the land, the camp needs to be recognized by UNRWA, but the land needs to be leased to UNRWA to get that classification. In such a situation, the state authorizes what is deemed “illegal” construction. However, the lack of official resolution pits the landowning families against both the state and the camp residents.

Today, Palestinians have been moving out of these camps to better neighborhoods in the ever-growing city. In the wake of the 2011 revolution and subsequent civil war in Syria, Palestinians have been renting or giving houses for free to Syrian refugees. So, as you can see, to understand how Syrians have come to find housing in Palestinian camps, one needs to excavate the layers beneath, all the way back to the city’s Ottoman layer. In such a layered understanding of land and housing, other refugee histories, urban histories, and legal structures are made visible.

Q: Your research involved conducting oral history interviews as well as taking photos of material signs documenting property rights. Can you describe your methods, and how these images help you shape your understanding of contemporary refugee issues?

My research relies on a mixed-methods approach that combines archival research in the Department of Lands and Survey and municipal and geographic collections with field-based methods, such as oral histories, on-site architectural documentation, and ethnographic research among refugees, attorneys, engineers, government officials, ethnic associations, local NGOs, and humanitarian-aid workers. To focus on lived experience and how people manage to build and claim property, I asked my interviewees to recount their families’ stories of migration (or more accurately expulsion) from Palestine, listening to what they felt was important without pushing for information. My interviewees were primarily first-, second-, and third-generation Palestinians. I followed multiple entry points to reach interviewees who varied by age and gender, and made sure to interview camp elders. My interviews were all carried out at people’s homes and conducted in Arabic; most were audio-recorded. They ranged from thirty-minute one-on-one conversations to group discussions involving several family members over hours and days. To build trust, I shared information about myself, my Jordanian origins, and my husband’s origins from Palestine.

During a four-hour-long interview with a Palestinian family, I learned about the continued use of Ottoman sale contracts (called hujja) for installing new electric meter boxes. Hand-written hujja contracts are widespread, and are used as property titles, for inheritance, buying and selling houses, establishing building guidelines, and demonstrating occupancy. To my suprise, I found out that various state entities, including the Jordanian Electric Power company, authorize the use of what are now deemed “non-legal” written property documents, including hujja contracts, to serve as property titles. Therefore, I began to take photos of house sale ads sprayed on buildings. I also asked my interlocutors if they would be willing to share these handwritten documents with me. Following this clue, during my house visits, I began to take photos of electric meter boxes installed by the Jordanian Electric Power. My focus on material signs extends the existing literature on land tenure and property disputes in the global South. It is, therefore, not surprising that a socio-legal reality is manifest in many objects, most tangibly in papers and architectural and urban artifacts.

Figure 4: An abandoned house in a legally contested Palestinian camp that Palestinian refugees gave to Syrian relatives in the wake the revolution turned civil war in Syria. The Syrian refugee family stayed in the house free of rent for almost three years (2013-2016). At the time of writing, the war in Syria was in its eighth year, the number of Syrian refugees in Jordan stands at 665,834 million, of which less than 20% live in UN camps, the rest that is more than 80%, have chosen to settle outside of officially administered UN camps, among communities primarily refugees themselves. Despite this wide discrepancy in numbers, Syrian refugees in cities and among local communities are typically referred to, in humanitarian reports and scholarly works, as “self-settled” refugees.

Q: The photograph above (Figure 4), which depicts an abandoned house, serves as a reminder of the contemporary war in Syria. How does your research address the ongoing war, and how did it shape the conditions under which you could conduct your research?

Because of the war, I have not been able to reach Syria. Before the war, for many people living in Amman and northern Jordanian cities, a trip to Damascus for lunch and back was part of routine life. After all, Damascus is less than 200 km away (around 120 miles). I remember my mother and her girlfriends going shopping and having lunch at their favorite restaurant in old Damascus during the weekend. The increasing securitization of national borders and, by extension, Syrian refugees affected who/what I could access when conducting fieldwork in Syrian refugee camps in the Syria-Jordan borderlands. For instance, when I was doing research in Za’atari refugee camp, the world’s largest camp for Syrian refugees, humanitarian organizations prohibited me from talking to refugees because refugees were considered too vulnerable to speak to researchers. In Azraq, another Syrian refugee camp, I was restricted from entering certain zones where Syrian refugees with possible ISIS connections are detained for fears of possible ISIS infiltration. Although my research primarily focuses on different groups of refugees in Amman, my fieldwork with Syrian refugees in the border region was shaped by the events unfolding in Syria and the increased influence of international humanitarian aid.

Q: Finally, you use Arab and Islamic traditions to understand contemporary networks of refugees. How do refugees provide assistance to each other, and what implications does this have for our understanding of refugees today?

As a student parent, I knew that I could not do one consecutive year of fieldwork, customary to the humanities and qualitative social sciences. So, from early on, I decided to conduct fieldwork over summers. In the summer of 2018, before my qualifying exams, I did pre-dissertation fieldwork on a grant from the Human Rights Center. During that summer, I worked with a local community development organization that works with women in Palestinian refugee camps.

I think that summer was a real turning point. During an interview with a Syrian refugee woman, I realized how she had been provided a house for free in a Palestinian camp. She told me how she escaped Za’atari camp to come to live with her distant Palestinian family members.

I began to follow clues. I interviewed the Palestinian families who gave their houses for free and gathered that these houses were abandoned. That is, Palestinians did not host Syrians inside the space of the home but in vacant houses. I came to realize that such practices of refugee-to-refugee sanctuary happen between family members, and not based on hospitality shown to a random stranger. Now, looking back, I think that this was my first “a ha” moment. Because of this interview, I began to look into Palestinian camps, which opened onto a whole world of Ottoman refugee shelter. I also noticed how Syrian refugees of Circassian origin were provided housing in the abandoned houses of Circassian-Jordanians.

This pushed me to take seriously what remains from the past, and consider transnational networks of family and kin, a connectedness that is partially related to the interconnectedness of Ottoman Syria. This also led me to investigate the Islamic notion of Hijra (migration), which carries the heavy symbolism of Prophet Muhammad’s migration from Mecca and his sanctuary among the locals of Medina. I found that Hijra, which also has connotations of abandonment and departure, overlaps with urban vacancy. The urban and architectural dynamics through which houses built by earlier refugees become re-inhabited by newer ones remain overlooked within the overstudied Syrian refugee crisis.