Viruses don’t recognize borders. Yet the labels and legal statuses that we assign to people can carry deadly consequences. The global COVID-19 pandemic is throwing into sharp relief the intersection of U.S. immigration and public health policies. We see the consequences for immigrants in inequities in the chance of getting sick or accessing health care, as well as the disparate economic and personal impact of the pandemic. Even though the virus is blind to people’s citizenship or visa status, immigrants can be especially vulnerable to infection, serious illness, financial hardship, and hateful discrimination.

To mitigate the dangers that immigrants face — and the repercussions for everyone in the United States — we need more public-private partnerships like California’s recently announced Disaster Relief and Immigrant Resilience Funds, serving California residents irrespective of immigration status. Researchers and students at the University of California, Berkeley, are also trying to do their part by assembling information on COVID-19 services for immigrants and documenting gaps in where vulnerable immigrant populations live and accessible health care clinics are located.

At-risk Immigrants

Immigrants are more likely to work in critical occupations that help the nation fight the battle against the coronavirus. Healthcare, eldercare, food services, daycare, delivery services, and agriculture are all industries with a disproportionate number of immigrant workers; they are also jobs that have been deemed essential services. Although immigrants made up only 17 percent of the U.S. workforce in 2018, immigrants accounted for 29 percent of all physicians and 38 percent of all home health aides. About half of the nation’s farm laborers, whose vital work helps secure the country’s food supply, are estimated to be undocumented, and another one in five have work authorization but no U.S. citizenship. The proportion of undocumented laborers working the fields in California is believed to be even higher. As these critical employees continue to work, this means that they — and their families — are on the front lines of exposure to the novel coronavirus.

Some immigrants may also be at greater risk for serious illness and death if exposed to COVID-19, whether they are working or not. Recent research suggests that long-term exposure to air pollution — prevalent in California’s Central Valley, home to many immigrant communities — is linked to more severe outcomes. Another risk factor, diabetes, also has a disproportionate impact on communities of color: at 12.5% and 11.7%, the prevalence of diabetes among Hispanics and non-Hispanic blacks is among the highest of all ethnic-racial groups in the U.S. Preliminary data from New York City’s health department shows that the age-adjusted death rate among Hispanics, at almost 23 people per 100,000, is more than double that of White or Asian residents (10 and 8 per 100,000 respectively), and slightly higher than for African Americans (20 per 100,000). Quite simply, immigrants and racial minorities appear to be at greater risk of serious illness and dying from COVID-19.

Barriers to access: Healthcare, fear of government, and language

Immigrants also confront more limited access to healthcare, even as they are at higher risk for infection and serious illness. Foreign-born residents, and especially those without citizenship, have significantly lower rates of health insurance, 81.1 percent and 71.4 percent respectively, compared to 93.2 percent for those born in the U.S. This can lead immigrants to delay seeking treatment or, in extreme cases, to avoid treatment altogether.

Beyond lacking health insurance or money to pay for care, some immigrants fear that going to a hospital might draw the attention of immigration authorities. Although U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) has issued guidance assuring immigrants that the agency will not conduct enforcement actions around hospitals or health clinics, many immigrants remain afraid of deportation and removal, given the Trump administration’s record of targeting them. The free and reduced-fee clinics that vulnerable immigrants trust are hurting, too, further undermining medical care. COVID shut-downs have forced health clinics like the Bay Area’s La Clinica de la Raza to reduce patient visits, resulting in a loss of $3 million in revenue in a single month. In California alone, over half a million migrant workers depend on these health clinics.

Immigrants may also be afraid to use health and public services out of fear that doing so could impact their legal status in the future. On February 24, 2020, a new “public charge” rule came into effect that bars immigrants from receiving green cards if they rely on public benefits, such as most forms of Medicaid or the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). The mere announcement of the public charge rule resulted in a chilling effect, leading some immigrants to disenroll from public benefits or refuse to use them, even if the rule did not apply to them or had not yet gone into effect. Federal immigration officials have encouraged anyone with COVID-19 symptoms to seek medical treatment, and they have publicly stated that doing so will not be part of a Public Charge analysis. Yet the existing fear and distrust created by the administration’s immigration policies carry real dangers for everyone’s health by leading immigrants to avoid or delay treatment.

These health risks are further exacerbated by linguistic barriers, as immigrants with limited English skills have a harder time receiving accurate and timely information about COVID-19, be it testing, physical distancing, the latest school and work closures, or other critical information. Language barriers affect a range of immigrants, irrespective of legal status, from recent refugees communities to long-established elderly immigrants. Nationally, one in five U.S. residents speaks a language other than English at home, and 25.6 million people report hardship in speaking English “very well.” A lack of English skills can lead to false or inaccurate information circulating in communities, undermining public health authorities’ best efforts.

Financial freefall without a safety net, and the dangers of hate

We know that the costs of COVID-19 go far beyond devastating health impacts, as millions have lost their jobs and the U.S. economy is plunging into recession. Like everyone else, many immigrants are facing financial hardships, though the impacts may be even more extreme. Foreign-born workers, both men and women, are more likely to be employed in service jobs than the U.S.-born (23.3 versus 15.9 percent, respectively), and are much less likely to be working in management or professional occupations that can be carried out online (32.7 versus 41.6 percent). Immigrants’ financial cushion is also thinner, as they earn, on average, about 80% of what U.S.-born workers make.

Many immigrants are thus highly vulnerable economically, but noncitizens — especially those in precarious legal status or without documents — face financial freefall without a safety net. The recently enacted Federal Relief Act does not cover immigrants without Social Security numbers, nonresident aliens, or temporary workers. Although many of these immigrant workers have been employed and paid taxes for years, they do not have access to unemployment benefits or other programs through the federal COVID-19 stimulus package. This is inherently unfair. American history provides lessons for a more inclusive response. During the Great Depression of the 1930s and in decades following, noncitizens — including undocumented immigrants — had access to a range of public benefits.

During the Great Depression of the 1930s and in decades following, noncitizens — including undocumented immigrants — had access to a range of public benefits.

The impact of COVID-19 on immigrants goes beyond health and economic stability. We are witnessing a rise in hate crimes against certain immigrant communities, notably those of Chinese or East Asian origin. These communities are suffering increased harassment and profiling due to the link between COVID-19 and China, a connection that has been repeatedly reinforced by President Trump and his administration. Sadly, just as healthcare workers of Asian origin serve on the front lines in fighting the pandemic, they also face increased racial discrimination due to COVID-19. Examples range from a doctor en route to work being told to “go back to f— China” to an Asian nurse who was spat upon while delivering medicine to a patient. Such abuse puts healthcare workers of Asian origin, who are already working under unprecedented stresses, under even greater strain, and it undermines the solidarity needed to battle the virus.

Our friends and neighbors: Protecting everyone

The bottom line is that everyone needs to be protected, physically, mentally, and economically, regardless of where they are born or their immigration status. If immigrants are more likely to be infected by the coronavirus, yet they delay or avoid medical care, or if they feel forced to keep working because they are not protected by government programs, this will extend and deepen the public health crisis for everyone.

We can take many steps, big and small, to tackle these challenges. We must stand up against racial harassment and ensure that information about COVID-19 is accessible to everyone, regardless of what language they speak or whether they can read. We need clear, multilingual information about what healthcare resources are available to immigrants, irrespective of health insurance, financial situation, legal status, or the new public charge rule. We must ensure that immigrants can access medical care, no questions asked. Future legislation that mitigates the financial impact of the pandemic must apply to all our neighbors and community members, just as programs established during the Great Depression were largely blind to citizenship, and so, too, is the recently announced California’s Disaster Relief Fund, which will direct $75 million to immigrants not covered under federal legislation. Philanthropists have a role to play, as well, as the California Immigrant Resilience Fund works to complement public efforts.

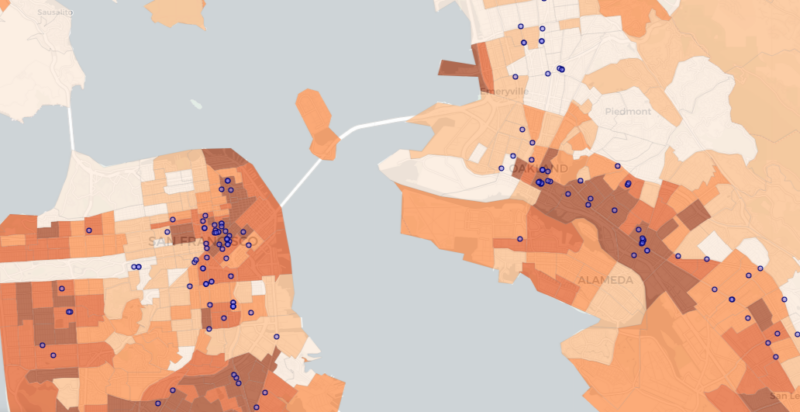

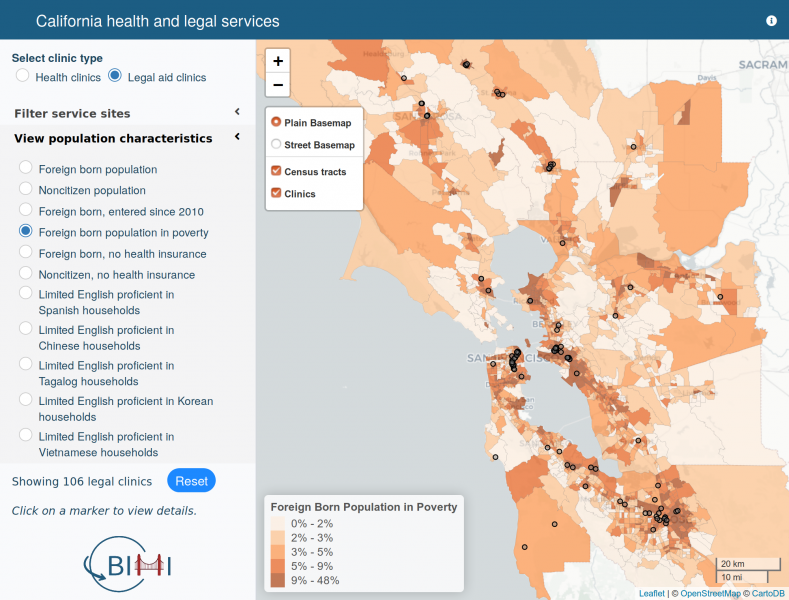

As researchers, we also need to be at the forefront of producing and disseminating more and better data about where at-risk immigrant populations live and identify gaps in healthcare access. As a step in this direction, the Berkeley Interdisciplinary Migration Initiative (BIMI) is developing an immigrant services mapping tool that overlays demographic data and the location of health and legal aid clinics serving vulnerable immigrant clientele in the San Francisco Bay Area and California’s Central Valley. Researchers at BIMI are also working to create an interactive mapping tool to identify health resources and at-risk immigrant populations across the entire United States. Such information can help policymakers, philanthropists, and service-providers identify the most pressing gaps in immigrants’ access to health services. UC Berkeley undergraduate students in the class “Contemporary Immigration in Global Perspective” are working to evaluate the resources available to immigrants in Bay Area counties, and they are developing recommendations to provide more inclusive services to immigrants in our region.

As researchers, we also need to be at the forefront of producing and disseminating more and better data about where at-risk immigrant populations live and identify gaps in healthcare access. As a step in this direction, the Berkeley Interdisciplinary Migration Initiative (BIMI) is developing an immigrant services mapping tool that overlays demographic data and the location of health and legal aid clinics serving vulnerable immigrant clientele in the San Francisco Bay Area and California’s Central Valley. Researchers at BIMI are also working to create an interactive mapping tool to identify health resources and at-risk immigrant populations across the entire United States. Such information can help policymakers, philanthropists, and service-providers identify the most pressing gaps in immigrants’ access to health services. UC Berkeley undergraduate students in the class “Contemporary Immigration in Global Perspective” are working to evaluate the resources available to immigrants in Bay Area counties, and they are developing recommendations to provide more inclusive services to immigrants in our region.

In the midst of this pandemic, UC Berkeley’s motto of Fiat Lux — “Let there be light” — guides our work to maximize the inclusion and protection of everyone, irrespective of where they were born. Viruses are blind to legal status, and our response to a pandemic must be, too.

About the Authors

Irene Bloemraad, Class of 1951 Professor of Sociology, is the founding director of the Berkeley Interdisciplinary Migration Initiative (BIMI). Dr. Jasmijn Slootjes serves as BIMI’s Executive Director and manages BIMI’s Mapping Spatial Inequality project. BIMI is a partnership of faculty, researchers and students who investigate human mobility, immigrants’ integration, and the ways migration transforms societies around the world.

Irene Bloemraad, Class of 1951 Professor of Sociology, is the founding director of the Berkeley Interdisciplinary Migration Initiative (BIMI). Dr. Jasmijn Slootjes serves as BIMI’s Executive Director and manages BIMI’s Mapping Spatial Inequality project. BIMI is a partnership of faculty, researchers and students who investigate human mobility, immigrants’ integration, and the ways migration transforms societies around the world.