Public education in the United States is profoundly unequal. Many public school systems are highly dependent on local revenues generated by local property taxes, meaning that areas with higher home values have better-funded schools. Wealthier people self-sort into areas with higher property values and better schools, while poorer communities have poorly funded schools. As a result, policymakers have asked: how can we solve the problem of inequality among school districts?

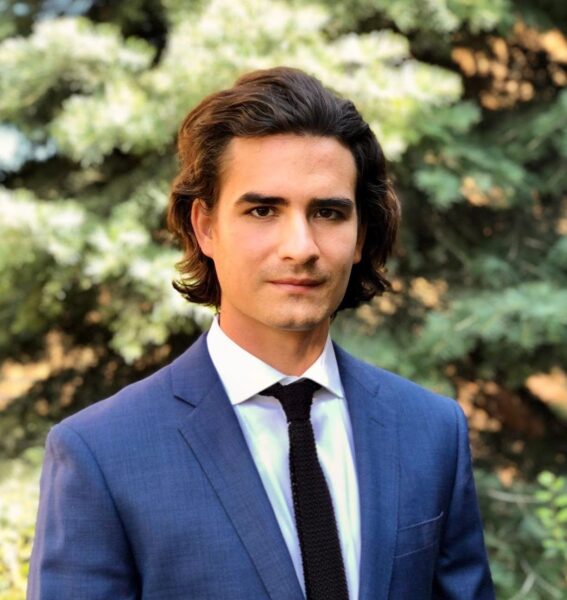

Quitzé Valenzuela-Stookey, Assistant Professor in UC Berkeley’s Department of Economics, has conducted research on how to address this thorny problem. Valenzuela-Stookey came to Berkeley after completing his PhD at Northwestern in 2021 and spending a year visiting Duke as a postdoctoral fellow. His main interests lie in the field of economic theory, and his research has broadly examined market-based policy design, allocation mechanisms, platform markets, and bounded rationality.

In part because of the longstanding effects of racial redlining, school districts in the U.S. have been profoundly shaped by legacies of racial segregation and inequality. While this might seem like a problem that a geographer or sociologist would study, how do you understand this as an economic problem?

It is impossible to understand the current state of geographic and racial disparities in income and education without recognizing the impact of policies such as racial redlining. These policies were designed to segregate people of color, protect the advantages in property wealth enjoyed by White families, and sustain school segregation. Redlining achieved all of these objectives.

Redlining achieved its discriminatory objectives by using the tools of economics. The term refers to a policy that designated homes as “high-risk” for lending purposes due to the presence of Black and immigrant communities in the neighborhood. Homes in these neighborhoods were usually ineligible for federally backed mortgages, and received disadvantageous mortgage terms. Redlining had far-reaching consequences, but one immediate and explicitly economic effect was that it prevented people of color from accessing credit to invest in capital, and thus inhibited their ability to accumulate wealth.

It is important to understand that while, at least in theory, redlining ended with the Equal Housing Act of 1968, the policy continues to impact areas such as housing and education to this day. This is where I think an economic understanding of the problem can play an important role. We need to understand the mechanisms through which the initial impacts of redlining on mortgage availability propagated to other areas of life, and how these effects were preserved and even magnified over time. For example, by reducing property wealth in redlined neighborhoods, these policies diminished the funding available for local schools. My own work touches on this mechanism. There is a self-sustaining process by which high property values support higher-quality schools, which in turn attracts richer people to an area and raises property values. This feedback loop helps perpetuate the discriminatory impact of redlining across generations. I study how tax policy today can be used to help redress some of these inequities.

The broad lesson is that policies do not exist in isolation. People live their lives in a web of economic systems, and changes to any one of these can have wide-ranging consequences. Economics as a discipline is largely about understanding the indirect effects that the actions of one person or institution has on others.

In part, you’re working with an economic theory from Charles Tiebout, who argued that, in efficient markets, people will move to areas with better service provision — in other words, that wealthier people might move to areas with better services. How did you model the ways that people do (or do not) select into different housing?

Tiebout’s theory is generally understood as an argument in favor of local control over the funding and provision of public goods, such as schools. The idea is that if some people really value a particular amenity, say education, they can choose to live in a district that provides it. They pay for the amenity by paying local taxes, which are set at the district level. People who don’t value education as much, or who value some other amenity relatively more, will choose to live in a different district and pay only for the amenities they want.

In essence, the argument is that by giving districts control over the type and quantity of amenities they offer, and giving them the power to tax, they essentially become firms that produce amenities and sell them in a market. The market is “free” insofar as people find it easy to move and, the classical thinking goes, free markets produce efficient outcomes.

While the analogy between location-specific amenities and markets for goods is useful, there are of course many problems with the classical Tiebout argument that this market will produce “good” outcomes. One important shortcoming is that the notion of efficiency, according to which idealized markets perform well, is limited: even if both rich and poor families value education the same in absolute terms, rich families will be willing to spend more to live in a district with good schools. It may be “efficient” for rich kids to go to better schools, but it is not desirable from a societal perspective. Moreover, the market may fail to deliver on even this limited efficiency criterion. This is exactly the problem my paper seeks to address.

In the model that I use, each district has a stock of houses that differ in terms of quality, and each family has a different level of wealth. Unsurprisingly, the model predicts that the richest families move to the best houses in the district with the best schools. The very poorest families move to the worst houses in districts with the worst schools. Middle-income families might choose to live in a better house in a district with worse schools, or a worse house in a district with better schools.

The upside of all this is that when a district raises taxes and increases expenditure on schools, it attracts a wealthier subset of the population. This in turn leads to higher property values in this district relative to what you would expect if there was no change in the wealth distribution of new arrivals. Higher property values benefit current homeowners, who are also the voters responsible for setting tax policy. This effect on property values gives the district an additional incentive to raise taxes, beyond what they would do if there was no mobility in the population.

The flip side of the dynamic I just described is that other districts receive a less wealthy set of new arrivals, which suppresses property values in these districts. This is what is known as a fiscal externality: the actions of one district impact how much money is available to local governments in other districts. Districts must compete with each other for the richest new residents by raising taxes and increasing expenditure. This competition leads to inefficient outcomes, but it also means that there is a policy intervention that can make all districts better off while reducing inequality in access to quality education: tax caps.

What are tax caps, and what would a tax cap look like for a school district?

The solution I propose is to cap tax revenue that the richest districts are allowed to collect. This can help alleviate a wasteful arms race in which rich districts compete for wealthier residents by investing in unnecessary amenities. A school may not need to build a second pool, but it might feel compelled to do so if the school in the next town over has done so. Importantly, the tax caps can be constructed in a way that these districts actually like. While each district would of course like to be free to choose its own tax and expenditure policy, each district also recognizes that they benefit if other districts can’t spend so much to lure away richer residents. At the same time, by reducing the disparity in expenditure between rich and poor districts, the caps imply that more middle-income people will move to the poorer districts. This allows the poorer districts to actually increase their expenditure on schools.

What are some of the other solutions that have been offered to the problem of property taxes determining school revenue?

Interestingly, many states, including California, do impose some type of cap on local property taxes, but these policies have generally not been tied explicitly to reducing inequality in education funding. High property taxes are a salient political issue. Indeed, the fact that many people feel their property taxes are too high is consistent with the idea that rich districts are engaged in wasteful one-upmanship. Tax caps are seen as a way to reduce people’s tax burden.

In California, the best-known legislation related to tax caps is known as Proposition 13, or Prop 13, a law passed by voters in 1978 to limit property taxes across the state. Prop 13 is really two different tax policies rolled into one. The first piece concerns the assessment of property values. Property taxes are specified as a percentage of a home’s assessed value, and this value is determined in different ways in each state. Prop 13 limits how much assessed values can change over time for properties in California.

The second piece of Prop 13 is a cap on the rate at which property can be taxed. Unless voters in the district approve an increase, the property tax rate cannot exceed 1% of assessed value.

Volumes have been written on the various implications of this type of policy. In the context of my work, one important issue with Prop 13 is that the expenditure caps are not tied directly to a district’s wealth or income. Moreover, the cap is in terms of the tax rate, whereas I suggest caps on aggregate tax revenue. The latter approach decouples the tax cap from the assessed value of homes in the area, which makes it easier to balance expenditure levels across districts.

An important piece of my policy proposal is that tax caps should be applied differently to rich and poor districts. The goal, after all, is to increase expenditure on schools in the poorest districts. It is important that poorer districts be able to increase their revenue when property values rise.

A related proposal, which I also discuss in the paper, is that districts be allowed to increase their revenue collection above the cap, but must pay a percentage of this additional revenue to the state government. You can think of this as a “luxury tax” on excessive expenditure. The state government can then transfer this money directly to poorer districts. In fact, Texas already has a system like this in place, which gives me hope that this type of policy could be implemented more broadly.

Another type of policy that has been proposed to deal with inequalities in access to education is simply to do away with the local control of funding altogether. The idea is to centralize education funding, say at the state level, and distribute funds equitably across districts. I think some version of this would be the ideal policy. Unfortunately, it is politically challenging. Rich districts that are currently able to spend only on their own schools will oppose efforts to redistribute funds to poorer districts. This is not to say that reforms along these lines are not possible. Illinois, for example, passed a reform a few years back that both increased state-level funding for education, thus reducing dependence on local tax revenue, and created a formula for equitably distributing these funds across districts.

What is the role of rental markets in your analysis?

This is an important question. The model I discussed above assumes that everyone is a homeowner. An increase in property values makes people who own property richer. This is the source of the competitive pressure toward higher expenditure. On the other hand, if rents increase because of an influx of wealthy residents, this hurts existing renters. In essence, increased expenditure on schools can exacerbate gentrification. If most residents of a district are renters, this means that the district has less of an incentive to increase spending than if most residents were homeowners.

If all districts have mostly renters, competition between districts could lead to expenditure on schools that is too low, and tax cap proposals could be counterproductive. Moreover, we might expect poorer districts to have a higher proportion of renters, and these are the districts where, by design, the tax cap raises property values.

Fortunately, a modification of the tax cap policy still works. One solution when poor districts have a high proportion of renters is to transfer money directly to poorer districts using the “luxury tax” system that I mentioned earlier. This would help offset some of the negative effects of higher rental rates, and still allow poor districts to spend more on schools.

What do you think policymakers can learn from your analysis?

I think there are two important takeaways. First, while people may be used to thinking about tax competition in terms of states or countries cutting taxes to attract investment, in the context of school funding, competition may have the opposite effect. In the fight for richer residents, districts may end up taxing more than is optimal. Second, this inefficiency is something that a policymaker can exploit to construct a policy that delivers on three seemingly incompatible objectives: reduced taxes in the highest-tax districts and increased funding for education in the poorest districts, all while making every district better off. The fact that every district benefits from the policy should make it politically feasible, unlike some other proposals to address these issues.