A team of researchers led by Leanne ten Brinke, a post-doctoral fellow in the Haas School of Business at UC Berkeley, published findings in Psychological Science that our unconscious minds detect lies more accurately than do our conscious minds. Although we are terrible lie detectors in the first place, this is a fascinating testament to the high level of processing conducted by our brains beneath our awareness.

In her study, ten Brinke asked 138 undergraduates to watch videos of “suspects” either lying or telling the truth about the location of a hundred-dollar bill hidden in a bookcase. The undergraduates had to identify whether each suspect was lying. As expected, they were pretty bad at detecting lies—on average, they performed at chance level.

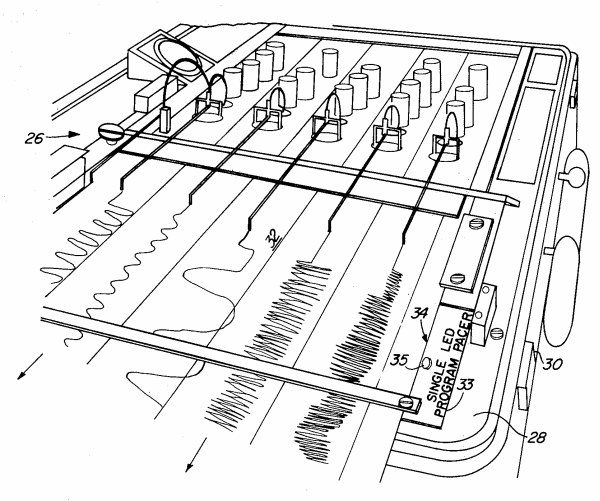

However, ten Brinke then tested the participants’ unconscious knowledge of whether each suspect had lied. To do so, she asked participants to perform one of two different tasks: one used frequently by psychologists (the IAT, or Implicit Association Test) and another designed by her team. In this latter task, participants were presented with still images of each suspect for only 17 milliseconds, not long enough to trigger conscious recognition. After each face image was flashed, the participants were shown a word. Some words were meant to convey honesty (e.g. “valid,” “genuine,” “honest”) and others are related to deception (e.g. “dishonest,” “invalid,” “deceitful”). Each word stayed on the screen until the participant categorized it as being truth- or deception-related using two response buttons, making their choice as quickly as they could.

The brain might detect lies in a deeper, less accessible corner of the unconscious.

This is where it gets interesting: participants were slower to classify a word as truth-related—and quicker to classify a word as deception-related—if the prior face image (which they never consciously recognized) was that of a suspect who had lied. This effect was far more accurate at detecting lies than participants’ own explicit judgments.

Before you try this at home, take note that even unconscious lie detection wasn’t that accurate: it had the equivalent of about 54% accuracy. This did, however, exceed the accuracy of conscious lie detection—around 50%—by a statistically robust margin. Moreover, it is unclear how effective the task was at probing participants’ unconscious minds. The brain might detect lies in a deeper, less accessible corner of the unconscious.

What makes this finding remarkable is not that we are great unconscious lie detectors (we’re probably not), but the fact that our unconscious minds can detect lies at all, even when we cannot detect lies consciously. Deception is presumably manifested in extremely subtle vocal tones, micro-expressions, gestures, and physiological signs like eye dilation and heavy breathing. The fact that the unconscious mind can pick up on these signals and interpret them without our conscious knowledge adds to a long line of evidence that we are smarter than we might otherwise think.

It is worth noting that some psychologists disputed ten Brinke’s findings. They claimed that the conscious lie detection performance reported in her study was unusually low—that people usually detect lies with 54% accuracy—and that this may explain why unconscious lie detection appeared to be more accurate than conscious lie detection. However, ten Brinke countered (and I would agree) that the suspects in her experiment were probably just good liars. Had they been merely average liars, then both conscious and unconscious lie detection may have been more accurate.

Ten Brinke, who was trained as a forensic psychologist, said she was motivated to join the Haas School of Business after hearing stories of corporate corruption in the news. “I recognized that my expertise in lie detection was not just relevant to criminal investigations, and I sought to apply my knowledge to the field of business,” she said. Perhaps we need regulators who are better at unconsciously detecting lies.