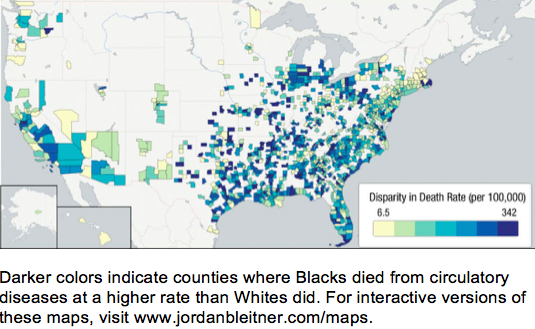

According to 2014 data from the Department of Health and Human Services, circulatory diseases kill black Americans at a higher rate than their white counterparts. In a recent paper, “Blacks’ Death Rate Due to Circulatory Diseases Is Positively Related to Whites’ Explicit Racial Bias: A Nationwide Investigation Using Project Implicit,” UC Berkeley Psychology postdoctoral researcher Jordan B. Leitner—together with co-authors Eric Hehman, Ozlem Ayduk, and Rodolfo Mendoza-Denton—established that these health disparities are positively related to the levels of racial bias within communities. We interviewed Leitner to discuss his research. [This interview was edited for length and content.]

Matrix: How would you summarize the main takeaways of your article?

Jordan B. Leitner: A main takeaway is that living in a racially hostile community is related to increased rates of death from cardiovascular diseases. This relationship between racial hostility and death rate is more pronounced for blacks than whites.

Matrix: How do you define a “racially hostile community”?

Leitner: We compiled data on racial attitudes from over one million respondents taken from a publicly available data set over the course of 11 years. What was really interesting was that these responses were geotagged, so we compiled the responses based on their geographical locations and aggregated them. For every county across the United States, we took the average of all the responses within those counties, which allowed us to generate one value for how racially hostile or egalitarian that particular county was. And in most counties there was a large number of responses over these 11 years.

Matrix: What motivated you and your coauthors to investigate this subject?

Leitner: A couple factors. One is that [the link between] racial disparity and cardiovascular health has been really pronounced and pervasive for many years, in that blacks tend to show poorer cardiovascular health compared to whites. So we wanted to understand whether one contributing factor to that disparity might be racial hostility from whites. It’s stressful to engage in interpersonal interactions with people who are biased against your group, and that stress over time has negative effects on cardiovascular health.

Leitner: A couple factors. One is that [the link between] racial disparity and cardiovascular health has been really pronounced and pervasive for many years, in that blacks tend to show poorer cardiovascular health compared to whites. So we wanted to understand whether one contributing factor to that disparity might be racial hostility from whites. It’s stressful to engage in interpersonal interactions with people who are biased against your group, and that stress over time has negative effects on cardiovascular health.

Additionally, it could be structural factors: if you live in a community where majority group members (in this case, whites) are hostile toward your group, you may expect that there may be structural inequalities that put your group at a disadvantage. So we thought that racial hostility might be one contributing factor to these disparities that we saw between blacks and whites in health outcomes.

Cardiovascular disease is the number one cause of death in the United States, so we thought that this was an important question to ask. Also, few studies have examined this question in this way; most previous research has asked this question (or attempted to answer this question) by asking black folks the degree to which they perceive being a target of discrimination, and then linking those perceptions to health outcomes. In this research, we didn’t rely on people’s perceptions of discrimination; instead, we tapped into what was going on in the minds of white people in these communities and linked that to the health of whites and blacks in those same communities.

Matrix: In your research, you made use of data from Project Implicit. One notable moment from the election was when Hillary Clinton referenced implicit bias in one of the debates, and this was the first time that some Americans had really heard of implicit bias on a national stage. What do you think is the level of public understanding of implicit bias?

Leitner: Based on the data that we have, implicit bias is quite pervasive. Over the past 11 years, racial bias at an implicit level has remained really stable. There was a paper published in 2010 showing that implicit bias barely changed after Obama got elected. I think some folks who criticized Hillary Clinton [after her implicit bias comment] alluded to this idea of “well, if we elected a black president, then clearly there can’t be implicit bias in our society anymore.” And the data shows that is not the case.

Despite the important advances that black people have had, there is still really strong implicit bias on a national scale. Advances in equal rights and reductions in really blatant discrimination don’t mean that implicit bias doesn’t exist. What we know is that implicit bias manifests in really subtle ways, and I think that’s what Hillary Clinton was alluding to—that we may not even realize that we have implicit bias. That’s one of the things that makes implicit bias so interesting and so difficult to study: often people don’t realize that they harbor these biases. They desire to be really egalitarian and it’s important to them to have egalitarian values, but still, at an automatic level, they seem to show some of these preferences toward some groups over other groups.

So I think that the public would benefit in understanding how difficult it is to detect all the biases that we have and to control them. It’s important to acknowledge that this is a challenge that most people in society face. My view is that if we acknowledge it and we have conversation about it, then we’re in a better position to do something about it.

Matrix: Let’s say you’re just an average person trying to reduce their implicit bias. Are there any steps you can take?

Leitner: There’s some research showing that there are ways to move around these biases. If, for example, you think about individual members of other groups as opposed to thinking about the group as a whole—particularly if you focus on positive examples of people that you like within that group—then that can help with some of these implicit biases. Having positive contact with people from other groups (if you make friends with people from different racial groups, for example) means you’re more likely to see less implicit bias. But I think we still have a lot to understand about how these biases develop and the best way to create a bias-free society.

The research that my colleagues and I have generated speaks to how important it is to continue to understand the role of racial hostility in public health.

Matrix: Do you think that your findings on racial bias and disparities in health outcomes would be cross-applicable to other minority groups?

Leitner: I do think that these findings would generalize to other groups; I don’t think that it’s specific to black/white relations. I have not done any other work with other groups, mostly because of the limitations of the data. For example, Project Implicit doesn’t have a measure toward Hispanics. The CDC does have data on Hispanic populations, but we don’t have good bias data on that. I have bias data on attitudes toward Muslims, but it’s tough to get health data that compares Muslims to non-Muslims, so it’s tricky. We can only answer certain questions, and those questions are shaped by the data available. But as we move forward, more and more data will become available. In particular, governmental health organizations are doing a good job of organizing the data that they have, so researchers like myself are going to be able to answer really interesting questions as more data become available.

Matrix: What’s next for your research?

Leitner: Right now I’m doing a few projects that try to understand the pathways through which bias might predict negative health outcomes. One potential pathway has to do with structural factors: perhaps in racist communities, blacks have less support from governmental healthcare programs, for example. I’m looking at whether a community’s level of racial bias predicts their support for Medicaid, because Medicaid is a program that disproportionately benefits black populations. We’re asking if states are less likely to expand Medicaid programs when the people in those states have more negative attitudes toward blacks. So that’s some work at the structural level.

I’m also doing some work more at the individual level, trying to understand the specific health processes that explain this link between racial hostility and death rates. One project is looking at whether black people show more unhealthy sleep patterns in communities that are more racist. And that would be theoretically plausible given that dealing with racial hostility is stressful, stress degrades sleep, and over time sleep has all kinds of negative health consequences. I’m currently working with folks at National Institutes of Health to compile some sleep data from across the country.

Matrix: Much of your work revolves around healthcare and uses data from public health organizations. Do you think that we need to see racism as a public health issue?

Matrix: Much of your work revolves around healthcare and uses data from public health organizations. Do you think that we need to see racism as a public health issue?

Leitner: Absolutely. I think some people have been pushing for that for some time. We’ve known about these racial health disparities for many years and it’s intuitive that racial hostility could be a potential contributor to these racial health disparities, but I think the research that my colleagues and I have generated speaks to how important it is to continue to understand the role of racial hostility in public health—and not just racial hostility, but social attitudes more broadly. It’s important to understand how attitudes toward all kinds of groups, from different religious groups, disabled or obese individuals, gender attitudes, all these different kinds of social attitudes, can play a role in the kind of healthcare that people receive and how their health evolves over time. I think that the broader issue is really understanding how our psychology and physical health are related to one another, across time and across geographical regions.

Top Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons, Image in Public Domain.